When Senate Democrats blew up the filibuster Thursday, they didn’t just rewrite some rules. They struck a mortal blow to a tradition that has blockaded effective action on climate change.

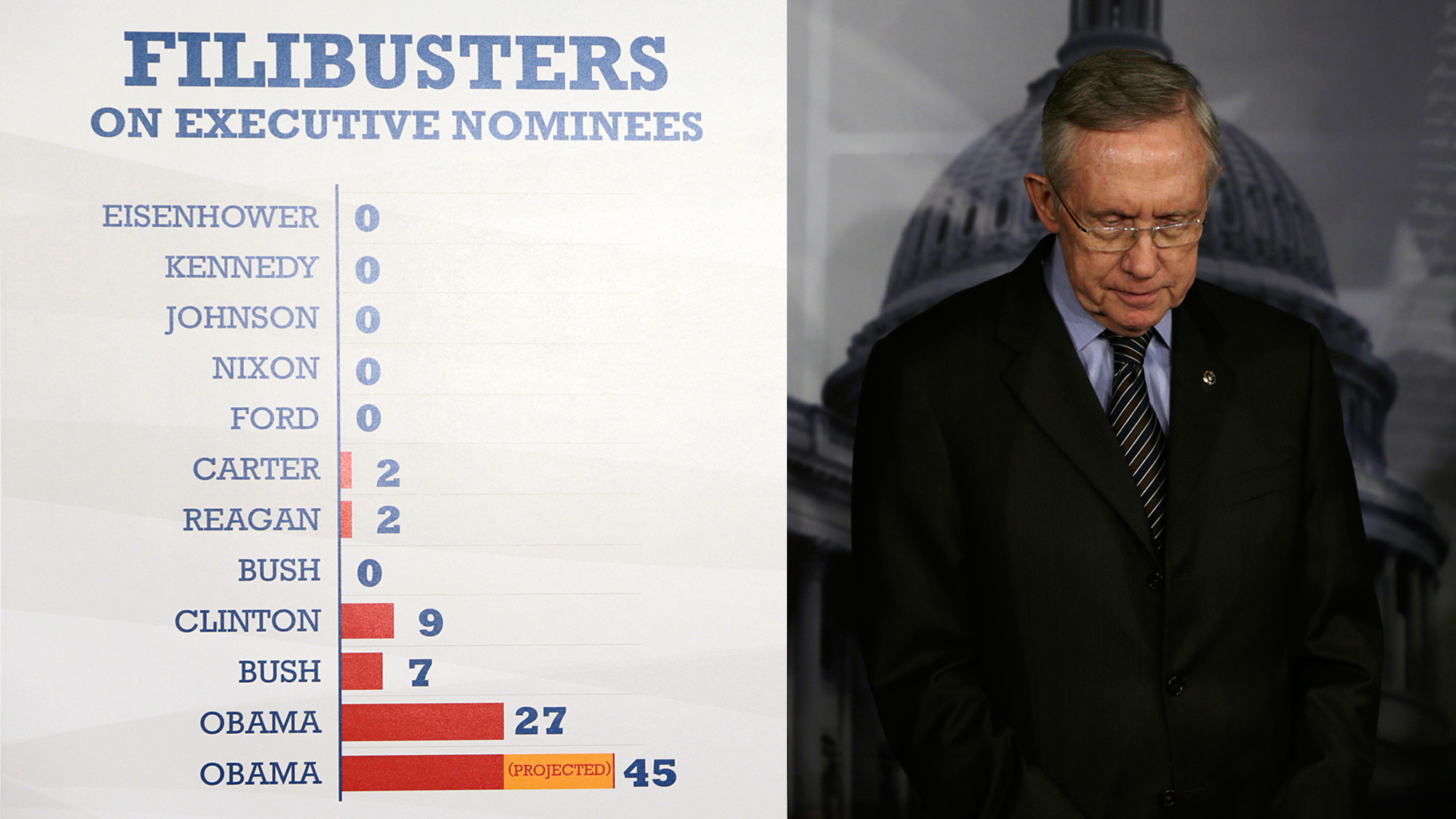

If you tried to summarize the cycle of hope and disappointment on climate policy during President Obama’s tenure, you’d bump into the filibuster at every turn. During Obama’s first term, Senate Republicans elevated the once-rarely invoked supermajority threshold required to end debate under Senate rules into a de facto 60-vote requirement to pass any legislation. Instead of merely voting against bills they opposed, the GOP filibustered all of them. They also filibustered executive and judiciary appointees.

Actually, they didn’t really filibuster at all, in the literal sense of blocking votes by refusing to give up the floor; that would have involved exhausting bouts of telephone-book recital and more bladder endurance than you’d expect to find in the aging legislature. All they had to do was threaten a filibuster to stop bills and appointments cold. Often they did not even have much of an ideological objection to the bill or nominee — they just wanted to gum up the works, to prevent Obama from governing effectively, and to make him look bad.

There have been plenty of victims of the filibuster: policies or nominees that remained dead in the water despite enjoying the support of the democratically elected president, the democratically elected majority in the Senate and (where applicable) the democratically elected majority in the House of Representatives. The public option in healthcare reform is one of the most famous, something liberals recall in frustration during every Obamacare-rollout setback.

But surely the biggest, worst victim has to be cap-and-trade. The Waxman-Markey climate bill passed the House in 2009. It could have garnered the 50 votes (plus Vice President Biden as tie-breaker) needed to pass the Senate. But now it needed 60 votes, and it failed. Then Republicans took control of the House, ending any hope of reviving a carbon-pricing law.

On Thursday, after five years of Republican filibusters holding back progress on environmental regulation, Senate Democrats began the process of restoring democratic accountability to their broken institution and eliminated the filibuster on presidential appointments (excluding the Supreme Court). The final straw for the Democrats, who’d been reluctant to invoke the so-called nuclear option: Republicans had refused to allow votes on three qualified, ideologically mainstream nominees to vacancies on the D.C. District Court of Appeals.

These vacancies posed a serious threat to Obama’s environmental agenda. Here’s why.

With a Democrat in the White House and Republicans in Congress, the executive branch is where environmental progress gets made, and the courts are where it is upheld or rejected. Thanks to the Clean Air Act, the administration has the authority to regulate CO2 as a pollutant. It has begun to do so, first with “tailpipe regulations” setting standards for cars and trucks, and now with forthcoming regulations of emissions from “stationary sources” — standards that will apply to large industrial emitters such as power plants.

The catch is that these rules inevitably get challenged in federal court by affected industries and their allies, such as the Chamber of Commerce and Republican state governments. Conservative ideologues appointed to the courts may be inclined to rule in their favor.

The Supreme Court is set to hear challenges on Dec. 10 to the EPA’s stationary source CO2 permitting authority and on the “good neighbor” rule limiting the air pollution that one state can pour into another. Both of these cases were decided by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals – which often ends up ruling on cases involving federal regulation, and often has final say, since the vast majority of its rulings are never reopened by the Supreme Court. Often, challenges to EPA regulations also go directly to the D.C. Circuit Court, not stopping at a district court. The Clean Air Act specifies that the D.C. Circuit has jurisdiction over any national regulation, rather than a regional district or appellate court.

“Many of us believe the D.C. Circuit is the most important court in the country for environmental health and safety protections,” says John D. Walke, director of the Climate & Clean Air Program at NRDC. “In 90 to 95 percent of Clean Air Act regulatory challenges, they are the only court to rule.”

For example, the Supreme Court declined to hear a number of challenges to other components of the EPA’s CO2 emissions regulations that were upheld by the D.C. Circuit Court. The stationary source regulations are being challenged too, but thanks to recent D.C. Circuit Court rulings, the tailpipe rules and the overall finding that EPA can regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant remain safe.

During George W. Bush’s administration, environmentalists often sued the EPA for not doing its job. Just as regulations can be challenged by industry for being too aggressive, they can be challenged by environmentalists for being too weak. As the landmark 2007 Supreme Court ruling in favor of regulation of CO2 in Massachusetts v. EPA demonstrates, when Republicans control the White House, the courts themselves are the only place where environmental regulations can be advanced.

Which brings us back to the D.C. Circuit Court and its makeup. Currently, there are four Democratic appointees on the court, one of whom was appointed by Obama. There are four Republicans. Three seats are empty, and six semi-retired judges are brought in periodically to alleviate the workload. Five of those stand-ins are Republican appointees. You can see the results of their handiwork. Putting Obama’s appointees in their place would make a big difference.

Circuit court cases are heard by a three-judge panel chosen at random, so it matters a great deal which judges you pull. In 2006, for example, two Republican appointees — Arthur Raymond Randolph and Karen L. Henderson — ruled in NRDC v. EPA that the NRDC lacked standing to bring suit against the EPA for crafting an overly permissive toxic regulation rule. The judges ultimately reversed the standing ruling but then ruled against NRDC on the merits.

“There are some judges with a strong ideological commitment to shrinking government, and we see that in many opinions, including some in the D.C. Circuit,” says Patti Goldman, vice president for litigation at EarthJustice. For instance, a 2011 D.C. Circuit Court decision, by two Bush appointees, tossed out the EPA’s “good neighbor rule” to regulate emissions of pollutants, including SO2 and nitrous oxides, which are found in soot and smog.

Senate Republicans proposed eliminating the D.C. Circuit Court’s vacant seats rather than filling them. Democrats reject this maneuver as a court-packing scheme. Republicans retaliated by filibustering any appointments to the court. So here we are.

Once Obama’s three D.C. Circuit nominees — Georgetown law professor Nina Pillard, U.S. District Court Judge Robert Wilkins, and Akin Gump litigator Patricia Millett — have been seated, the “senior judges” appointed by Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush will be used less frequently. Historically, filibusters of judicial nominations were reserved for unqualified cronies and ideological extremists, but that just isn’t the case here.

Millett, for example, worked in George W. Bush’s administration as well as Bill Clinton’s, and she has argued the second most cases before the Supreme Court of any woman. She is clearly qualified and non-ideological.

“When you have Republicans rejecting Patricia Millett, a renowned Supreme Court litigator who represented all kinds of business interests, and was endorsed by [Republicans] Paul Clement and Kenneth Starr, this is outrageous,” says Simon Lazarus, senior counsel with the Constitutional Accountability Center, a public interest law firm and think tank. “There’s no excuse for this kind of behavior, so there was no alternative.”

A number of important environmental cases are in the D.C. Circuit Court’s docket.

White Stallion Energy LLC et al v. EPA asks the court to strike down EPA rules limiting mercury pollution from power plants. In National Association of Mining v. EPA, also slated for the Circuit Court, the coal industry won a lower court ruling against the EPA. The agency, the court said, had exceeded its authority when it asked states in 2011 to consider conductivity levels of stream water when issuing mining permits. This matters because it’s a critical part of the agency’s effort to reduce the impact of mountaintop-removal mining.

The D.C. Circuit is the highest-profile arena to feel the impact of the Senate’s filibuster busting, but the move will help fill critical judicial vacancies throughout the federal bench. Currently there are 53 nominees awaiting votes — 43 for district courts and 10 for appeals courts.

There is also a downside for environmentalists: In 2017 there may be a Republican in the White House, a Republican majority in the Senate, and no more filibuster to prevent the most extreme anti-government appointees from being seated. But political and legal experts say the Republican Party has been so captured by its most uncompromising elements that they would have eliminated the judicial filibuster then anyway. They have, after all, been threatening to do so since 2005.

“The Republicans would have done this if they got a majority in 2016,” says Lazarus. “I have no doubt Mitch McConnell, in his heart of hearts, would prefer to use the filibuster more sparingly. But those sentiments don’t win Republican primaries.”

With both parties now freer to appoint whomever they want when they are in office, we might see wider swings in environmental enforcement.

“It does mean the stakes of presidential and senatorial elections have been greatly increased with respect to a bunch of issues that much of the Democratic public is not used to focusing on,” says Lazarus. “The environmental movement needs to worry more about who gets named to the courts more than its members usually have.”