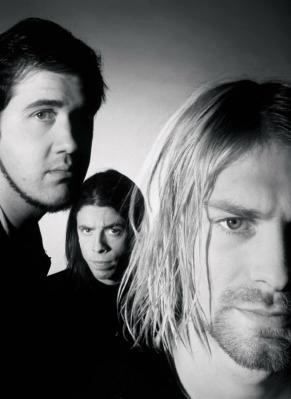

Who are those other guys? Krist Novoselic, left, in Nirvana's heyday.

If you were an angsty adolescent during the late 90s, you probably had an intimate relationship with Krist Novoselic in your black-décored bedroom. The name might not ring a bell at first, but the man on bass below Kurt Cobain’s guitar and vocals on the Nirvana records you listened into the ground? That’s Novoselic.

Unlike other rock stars past, Novoselic isn’t spending his post-headlining days lying around a mansion with an army of un-housebroken dogs (nice goin’, Ozzie) or out trying to recapture glory during the current grunge revival (howdy, Chris Cornell!). Instead, he’s trying to change the way we do democracy in the United States by convincing people to adopt an obscure (by U.S. standards) election system known as ranked choice voting (RCV).

It’s a long shot. But success could mean a huge leap forward in broadening campaign dialogue, civilizing partisan warfare, and giving oft-marginalized environmental issues serious political clout.

—

So how did a prince of rock nobility become a wonky election reformist? Novoselic defies almost every possible expectation you might have of a member of the band that ushered in the grunge era. He speaks to me by phone from his home in southern Washington state’s rural Wahkiakum County, where, seriously, he cuts his own wood. “I’m sitting next to my fire right now,” he observes, before he begins ruminating on the nuances of international election laws.

Novoselic appreciates that his current work in politics might be surprising, given his rocker past life in the 80s and 90s. He asks my first question for me: “This dude is a bass player — why is he involved in election reform?” he says.

But Novoselic explains that music launched his life in politics.

In the early 90s, the Washington state legislature passed a law restricting music sales to minors, and Seattle had laws keeping underage fans out of most venues. To fight the rules, Novoselic and other members of the then-exploding Seattle music scene banded together, forming J.A.M.P.A.C. — the Joint Artists and Music Promotions Political Action Committee.

Trying to change music laws alongside Soundgarden frontman Chris Cornell at the state legislature “was kind of my civic education,” Novoselic recalls. While working with state legislators, “I started recognizing these flaws. Why have a ‘get out the vote’ campaign when an incumbent state senator in Seattle is going to win?”

Convinced there had to be a better way to vote, Novoselic booted up his computer, and, this being the ’90s, waited while the modem buzzed, beeped, and screeched, then started searching. He found Fair Vote, a nonprofit formed by former independent presidential candidate John B. Anderson, which is devoted to bringing RCV or a similar system to ballots everywhere.

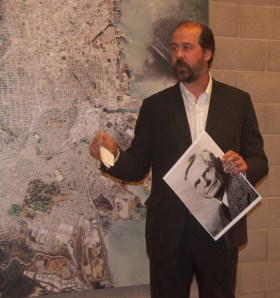

Voting rights are so punk rock: Krist Novoselic at the 2010 Global Forum on Modern Direct Democracy in San Francisco. (Photo by Steve Rhodes.)

Here’s how RCV works: Rather than a system with primaries followed by general elections, all the candidates for an office run in a single election. Voters then rank their top choices in order of preference. So imagine the 2000 presidential election: There would be only one election and voters could have ranked their top three preferences. Ralph Nader could be your top choice, Al Gore your second, and Mickey Mouse your third.

The votes are tallied in rounds starting with the first choice. The lowest vote-getter is dropped and the second choices of the people who supported him are distributed to the rest of the candidates. So if your picks were Nader-Gore-Mickey, and Nader got the fewest votes in the first round of counting, Gore would get your vote in the second round.

In theory, this system gives third-party candidates a better shot at being elected. They are able to campaign through to the general election, and getting a slew of second-choice votes could be enough to push them above a Democrat or Republican.

In practice, a third-party candidate (or fourth or fifth) isn’t much more likely to win under RCV than any other system of voting — big party money and incumbency being what they are.

But Novoselic says the need to be someone’s second or third choice to ensure victory means that campaigns are less negative, and candidates have to try to appeal to more and wider interest groups. If a Democratic mayoral candidate runs primarily on health care issues, she still has to address the environment to appeal to Greens in hopes of being their second choice.

“The prevalent voting methods today, they screen out issues and candidates and parties that are not primarily focusing on whatever the No. 1 concern — the issue of the day — is,” says RCV fan David Zwick, founder of Clean Water Action.

Zwick, who now works with Fair Vote’s Minnesota chapter, says that polling regularly shows people care about the environment, but it isn’t their No. 1 concern, so major candidates don’t spend as much time talking about it. RCV, he explains, “gives a bigger voice to more issues and to candidates representing more issues.”

For environmentalists, that means perennially underserved topics like climate change get a shot at a little more love and attention.

—

St. Paul, Minn., adopted RCV before its city elections last fall, and all those great things Novoselic claims come with RCV happened, says city council candidate and Green Party member Jim Ivey. “I experienced all those positive effects.”

His opponent, Dave Thune, was a repeat incumbent; Ivey had no name recognition. Thune had the backing of St. Paul’s powerful Democratic Party. Ivey had to confront people still angry over their perception that Ralph Nader stole the 2000 election from Al Gore.

But Ivey still managed to finish in second place among six candidates, leading to a photo finish with Thune. The day after the first round of counting resulted in no clear victory, Ivey called Thune and asked if he wanted to meet for coffee — that’s how amicable the campaigning had been.

Ivey suspects that without RCV, Thune would have run a fear-based campaign against him, warning voters that if they wasted a vote on Ivey, the leading conservative candidate would clinch victory. Instead, they practically ended up campaigning for each other.

“You could say, ‘The guy I’m running against is a great guy,’” Ivey says. He encouraged fellow green-thinking environmentalists to put him in the No. 1 spot, but to give their second choice to Thune.

“That’s a classic ranked choice dynamic,” Novoselic says. “They reach out, they’re building a coalition.”

Turning it up to 11 on some pesky rural Washington brambles. (Photo courtesy Krist Novoselic.)

In return, Thune had to campaign — if not for Ivey — then at least for the environmental second-choice vote. By the end of the campaign, in-city agriculture was a major part of Thune’s platform. “I’m real high on urban gardening now,” Thune told MinnPost.com after winning.

Ivey didn’t win the office, but the planet picked up a small victory by incentivizing a mainstream candidate to consider and eventually adopt outside ideas.

Ranked choice voting still has a long way to go before it leaps from a few cities to mainstream acceptance in the U.S. San Francisco adopted RCV in 2004, but efforts to end it are gaining steam. This February, a proposed ballot measure repealing RCV nearly passed in a 5-6 vote by the city Board of Supervisors, leading to a condemning editorial by the San Francisco Chronicle. The paper argued RCV “produced voter confusion and vacuous campaigns.”

“It takes voters some time to adapt,” acknowledges Phillip Ung, a spokesperson for RCV advocates California Common Cause. “It takes time for third-party candidates, and candidates in general, to get used to campaigning in a ranked choice voting system.”

(Ung might also want to point out that voters in the country that gave us the criminally dumb Crocodile Dundee seem to have been capable of figuring out RCV.)

In Novoselic, who now chairs the board of Fair Vote, the issue has a backer with the kind of name-recognition and pop-culture reach most individual candidates can only dream of. From that position, he lobbies local governments and legislators to adopt RCV — or its close cousins Instant-Runoff Voting and Proportional Voting. He also blogs about movements around the country to expand democracy’s reach.

One day after speaking with Grist, Novoselic hopped a plane to attend a conference at NYU boasting the ambitious title “United Citizens: How We Revive Our Democracy.” Now studying for a Bachelor’s in the social sciences at Washington State University, he is a perpetual student of new ideas to, as he says it, “put the power in the hands of the people.”

Before grunge was perverted to sell flannel and Xeroxed into oblivion by scourge-of-the-Earth bands like Creed, it actually argued for substance over style in music, and often allied itself with movements of empowerment and political progression. “Coming out of the punk rock world, we had a healthy dose of it,” Novoselic reminisces.

In that respect, perhaps his crusade isn’t so shocking. He just found a way to help those ideas mature into something that might effect lasting change. If a few more of his grunge-era rock ‘n’ roll comrades follow suit, we’d all be better off.