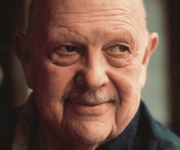

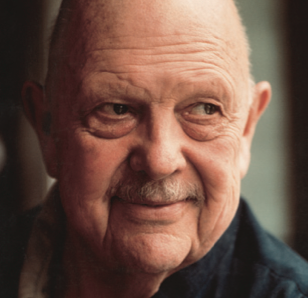

The man himself, James BeardTwo miles north of Zuccotti Park, where Occupy Wall Street‘s encamped, there’s another would-be hotspot of cultural change occupying a more genteel locale: the James Beard Foundation (JBF).

The man himself, James BeardTwo miles north of Zuccotti Park, where Occupy Wall Street‘s encamped, there’s another would-be hotspot of cultural change occupying a more genteel locale: the James Beard Foundation (JBF).

Seriously? This epicurean epicenter housed in an elegant West Village brownstone with eternally well-tended window boxes, wants to stir up something more culturally significant than mouth-watering meals curated by celebrity chefs?

Well, yes. And it’s a logical move, if they don’t want to see their legacy (or their democracy) go down the toilet. After all, as Mario Batali once pointed out on CBS Sunday Morning, “When you think about it, all my greatest work is poop, tomorrow.”

Ah, but not all excrement is created equal. On the one hand, intensive pork production’s given us vast pools of lethally toxic pig shit known as manure lagoons, more akin to radioactive waste than organic manure. On the other hand, there are worm castings, the highly fertile poop extruded by earthworms that looks like coffee grounds and smells pleasantly earthy.

The respective hazards and merits of various manures has not, historically, been the province of the JBF. This highly influential culinary center, founded after the legendary chef and cookbook author James Beard’s death in 1985 at the age of 81, is better known for its awards honoring outstanding chefs, restaurateurs, and writers.

But with the current American diet in such a dire state, the JBF folks are not content to simply celebrate culinary and literary excellence. Eager to play a more proactive role in reshaping our food system, the JBF has come down squarely in favor of a future that features more worm castings and fewer manure lagoons.

The JBF promoted that vision last week with its second annual JBF Food Conference, How Money and Media Influence the Way America Eats. In conjunction with the conference, the JBF also held its inaugural JBF Leadership Awards [PDF], which honored 10 “visionaries in the business, government and education sectors responsible for creating a healthier, safer, and more sustainable food world.”

Fittingly, one of the honorees was vermicomposting genius Will Allen, whose internationally acclaimed nonprofit Growing Power flourishes on a foundation of worm poop.

And while the JBF’s newfound fervor to reform our food chain may seem like a radical departure, it’s really more like a homecoming. James Beard, whose influence led Julia Child to declare him “the Dean of American Cuisine,” was advocating pure, regional, seasonally based home cooking half a century before Alice Waters and Michael Pollan sought to popularize that ideal.

Beard despised the prepackaged convenience foods that had already begun to displace real meals in his heyday. In a letter to his friend Helen Evans Brown in September of 1954, he wrote:

The food editors’ conference is going full tilt and we hear the results are horrifying. Soon, we are told, there will be no fresh foods on the market — just canned or frozen (this came from the lips of the Secretary of Agriculture).

The JBF Food Conference, co-hosted by Good Housekeeping at their conference facility in the LEED gold certified Hearst Tower, brought together chefs, scholars, entrepreneurs, economists, writers, advocates, and representatives from nonprofits and corporations to examine the financial underpinnings of our food system and the media’s role in shaping our food choices.

The goal was to find common ground among people with diverse agendas, and “establish a set of guiding principles around which we can organize and move forward together,” as the conference’s facilitator, Joseph McIntyre, announced at the outset.

McIntyre, president of the California-based think/do tank Ag Innovations Network, came to town a few days early to make a pilgrimage to Zuccotti Park.

I wanted to go down there and see what was going on. And you know what they were talking about? Money and media. I would argue that our friends in the Tea Party are talking about the same things. Underneath the great debate in America today about food, about finance, underneath the polarized positions between Occupy Wall Street and the Tea Party, lie common aspirations for the future. How many of you do not want a world that’s better for your children?

The JBF’s Leadership Awards, which offer prestige but no monetary prize, personified the paradoxes that bedevil the good food movement. Michelle Obama, Alice Waters, and the aforementioned Will Allen were obvious shoo-ins, as was Fedele Bauccio, whose Bon Appétit Management Company has been the gold standard when it comes to sustainability in the food service industry.

Other honorees whose bona fides were impeccable included Debra Eschmeyer, the dynamic co-founder of the just-launched FoodCorps; the venerable Fred Kirschenmann, of the Leopold Center For Sustainable Agriculture and Stone Barns; and author/professor Janet Poppendieck, whose books Sweet Charity and Free For All: Fixing School Food in America offer thoughtful analyses on the root causes of hunger in our society and how to reform our shoddy school lunch program.

But the inclusion of executives from Costco, Unilever, and Sysco no doubt surprised some folks. Forbes writer Nadia Arumugam was pleased to see them included. She said:

… witnessing three high-level executives from three large corporations receive awards for their tangible and results-driven efforts to further the sustainable food movement, was surprising, but extremely heartening.

This is where the pragmatists and the purists collide. As Naomi Klein told Civil Eats, “The food movement is inherently anti-corporate and it is inherently about rebuilding a real economy.”

In honoring corporations who are making incremental changes that merit our support, the JBF challenges that assumption. And what are we to make of the partnerships that two of the honorees, Michelle Obama and Will Allen, have forged with Walmart?

It’s a dilemma that James Beard would have understood. As David Kamp noted in The United States of Arugula, Beard labeled himself a “gastronomic whore” after entering into an endorsement deal with Green Giant to tout their Corn Niblets and wax beans in his recipes:

In his heart, Beard knew that lending his name to processed foods was a betrayal of his core beliefs in seasonality and regionality … but his cooking school required a lot of money to operate, and his ever-increasing number of writing commitments required a full-time retinue of testers and gh

ostwriters.

Where does compromise end and co-option begin? As Walt Whitman famously said, “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.”