An arctic wind cut across Prudhoe Bay, sending spindrifts swirling as Energy Secretary Chris Wright stepped onto a podium hastily erected among oil wells and pump stations. The gray summer sunlight scattered over ice-rimmed ponds, shadows gathering in the hollows of low heaves and stretching over the tundra. But the visitors gathered around him were less interested in the scenery than what lay beneath it.

Wearing a hard hat perched above a pair of safety glasses, Wright gripped a lectern with red-knuckled hands chilled by the cold air. “I want to say to all of you standing here today,” he told a gaggle of oil workers, “you are the greatest liberators in human history.”

Andrew King / DOI

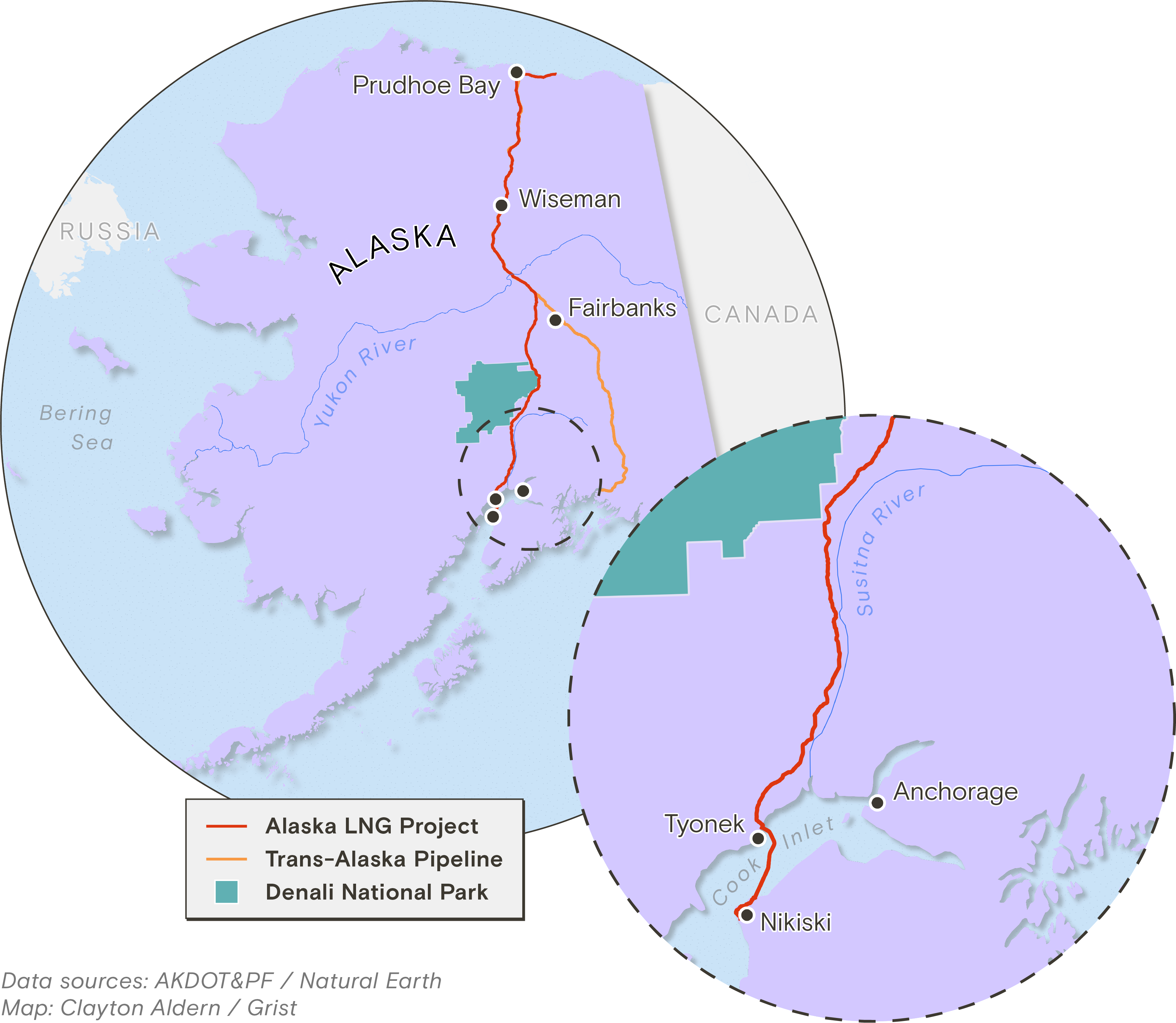

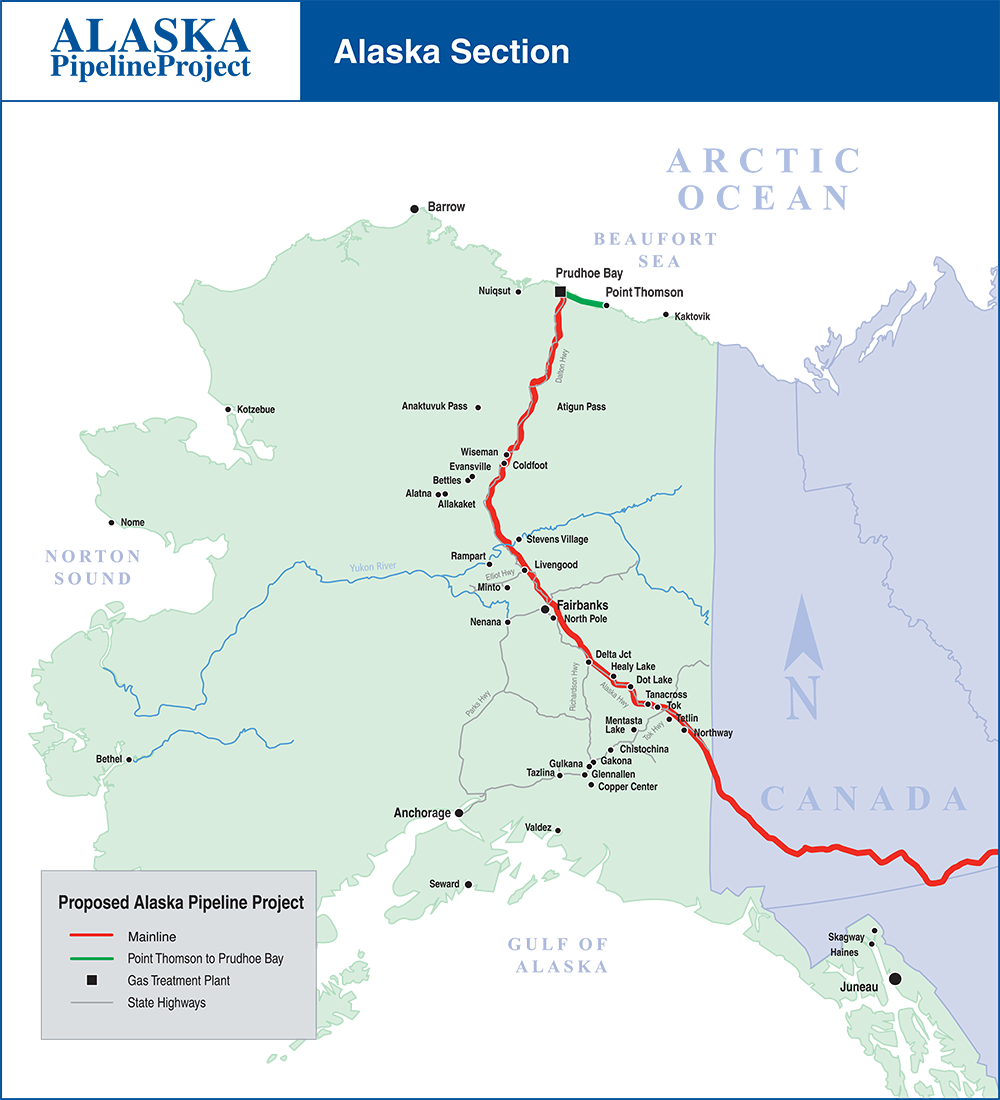

Hovering nearby were Interior Secretary Doug Burgum and Lee Zeldin, head of the Environmental Protection Agency. It was the kind of Cabinet-level entourage that made the remote industrial site feel like a campaign stop. They were on a multiday tour of northern Alaska, hyping plans for a pipeline that would carry liquified natural gas, or LNG, roughly 800 miles south to an export terminal on Cook Inlet. If built, it would be one of the largest infrastructure projects in U.S. history.

Since his first day in office, President Donald Trump has focused on “unleashing Alaska’s extraordinary resource potential.” He has hailed the liquid natural gas project — an idea that has been kicking around since the 1960s — as “truly spectacular.” It has become a centerpiece of his energy agenda, even as scientists warn that emissions must fall to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Proponents like Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy extoll the economic benefits the pipeline will bring to Alaska and the energy security it will provide to allies. But the cost is staggering: Official estimates put it at $44 billion, though independent analysts suggest it could top $70 billion. Experts say it has required substantial government support to develop and will require “a mix of public and private capital to move forward.”

The North Slope of Alaska holds about 35 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, making it one of the largest known sources in the United States. But with the project’s steep price tag and no firm commitments from buyers, oil majors like ConocoPhillips and Exxon Mobil have backed away over the last decade. Glenfarne Group, a privately held energy firm that has never operated a liquified natural gas export terminal, stepped in last year. Shortly after Trump was elected, state officials handed the company a 75 percent stake in the project in a no-bid deal, the details of which have been kept even from the legislature. Glenfarne will lead the project’s development and financing efforts and, if the company decides to move forward, oversee construction and operation of the pipeline, gas treatment plant, and export terminal. Though the state has not paid Glenfarne directly, it has poured at least $600 million into planning, design, and permitting — and initially floated paying Glenfarne an additional $50 million for its costs, even if the company decided to walk away.

Despite repeatedly tapping state coffers to keep the project going, Brad Chastain, the project manager for the Alaska Gasline Development Corp., the publicly funded entity created to advance the pipeline, told Grist at a recent public meeting, “There are no subsidies.” The corporation denied Grist’s public records request for the state’s contract with Glenfarne, citing trade secrets. It also claimed the publication had no right to appeal its rejection.

The pipeline’s backers are already eyeing additional federal support, including $30 billion in loan guarantees. That backstop would leave the public on the hook if the endeavor falters, an outcome that has plagued previous state megaprojects. “Every taxpayer should be furious that the federal government is chasing this project,” said Cooper Freeman, the state director for The Center for Biological Diversity, which is suing the federal government over the proposed pipeline’s threat to endangered species.

Beyond the financial risks lie grave climate impacts. According to the Department of Energy, the pipeline, export terminal, and related infrastructure could add at least 1.5 gigatons of emissions over its 30-year lifespan. “It’s public funds flowing to support these private companies, while worsening the climate crisis at a critical window,” said Phil Wight, an environmental historian at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Alaskan oil and gas have always flowed through the shadow of global politics. Where the gravel shores of this continent meet the ice-flocked waters of the Arctic Ocean, the Iñupiat long ago noticed dark stains on the rocks and rainbow sheens in the muskeg. Millennia of tectonic forces had transformed plankton and silt into oil, soaking tundra that Alaska Native people would cut into blocks and burn during long, dark winters.

1959

Alaska becomes a state.

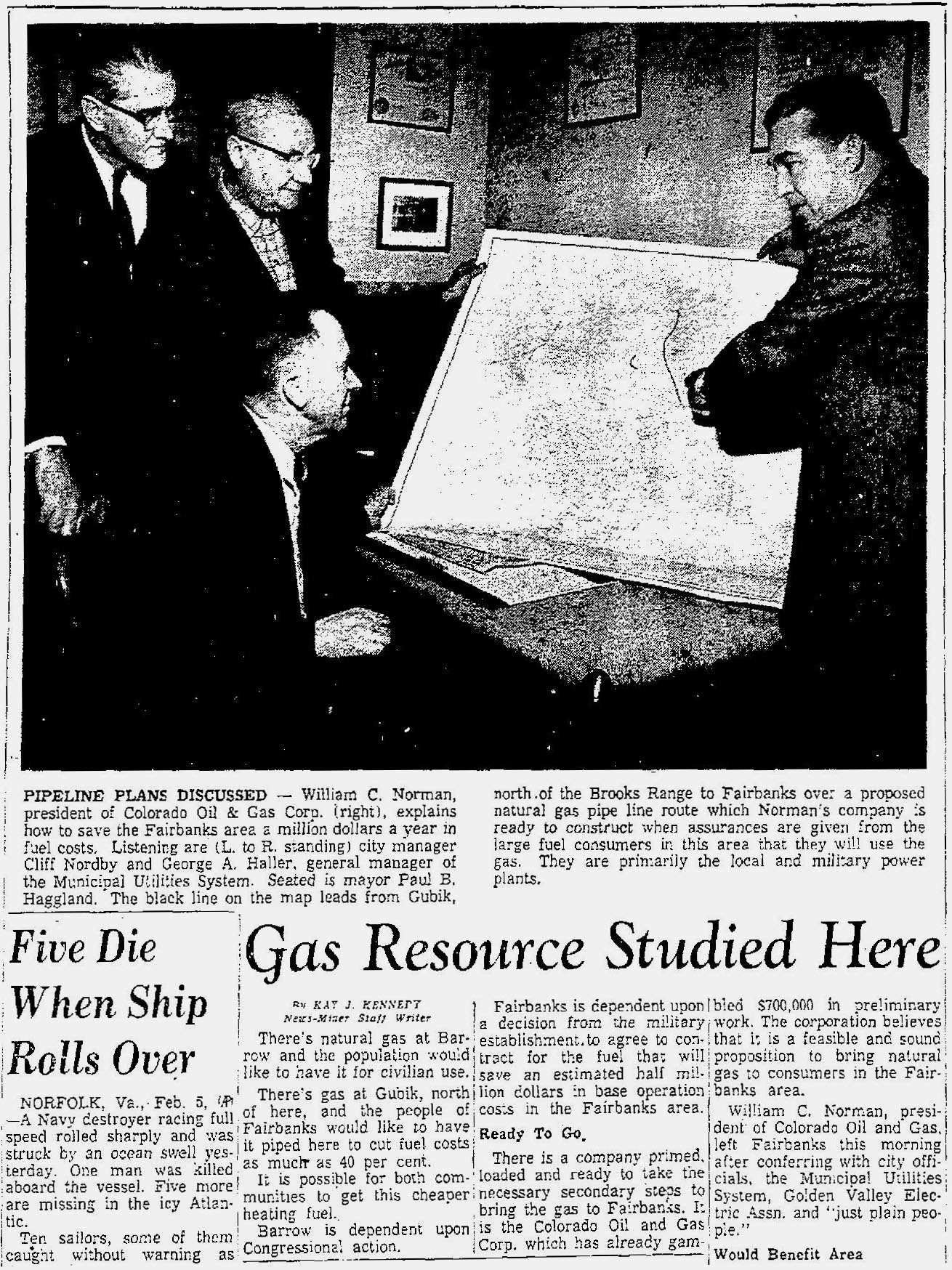

By the 1950s, this resource caught the attention of a world hungry for energy. As the race to tap the state’s vast oil and gas reserves got underway, Colorado Oil and Gas Corp. became the first to propose a natural gas pipeline from the northernmost reaches of the state to the city of Fairbanks. It was never built, but gas soon flowed to U.S. Navy facilities on the North Slope, even as Indigenous communities were barred from tapping it.

1960

Colorado Oil and Gas Corp. proposes the first gas pipeline from Alaska’s North Slope to Fairbanks. It is never built.

The disparity angered Iñupiat leaders like Eben Hopson. He helped the Arctic Slope Native Association file a protest that clouded the land’s title, and in 1966, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall froze development until its arguments were addressed. Impatient energy companies pressed for a deal. The government eventually gave newly minted Alaska Native corporations 44 million acres and nearly $1 billion, clearing the way for construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, which carries crude oil across the state.

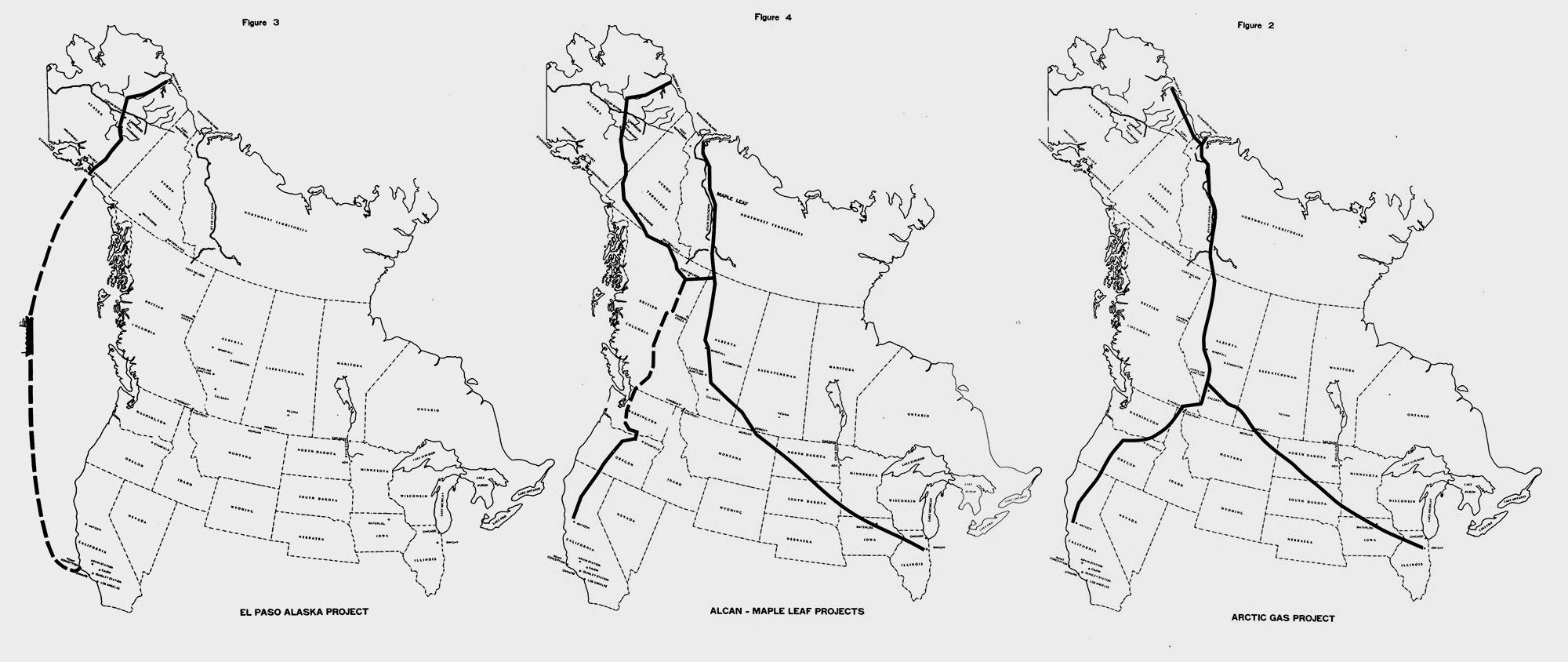

1974–1976

Three competing gas pipeline proposals (El Paso, Alcan, and Arctic Gas) spark 253 days of federal hearings. None are approved.

2007

TransCanada/ExxonMobil routes are proposed.

In the decades since, there have been more than 23 proposals to carry the region’s natural gas south. Presidents as far back as Jimmy Carter heralded the idea as a matter of national security, but the harsh conditions, extreme distances, specialized equipment, and highly variable markets made it a gamble no investor could justify. Still, the dream persists.

2008-2011

BP’s Denali version is proposed. Three years later, it is canceled.

“These projects, they never die, they just don’t happen,” said Larry Persily, who spent five years as the federal coordinator for Alaska Natural Gas Transportation Projects, an agency Congress established in 2004 to advance a pipeline for North American markets. That office disbanded in 2015 due to a lack of funding, as the state turned its attention from developing a domestic market to exporting liquified natural gas. After it created the Alaska Gasline Development Corp. in 2010 to lead that effort, the corporation spent about half a billion dollars. It has yet to reach the construction phase.

Nevertheless, President Trump’s quest for energy dominance has revitalized the idea, leading to Wright and the Cabinet’s northern roadshow in June. The tour’s next stop was 600 miles south in Anchorage, where Governor Dunleavy hosted the Cabinet members at a sustainable energy conference, whose sponsors included Glenfarne and oil giants like Repsol. (The governor declined interview requests.) Outside the Dena’ina Civic and Convention Center, protesters held hand-painted signs declaring, “Alaska Is Not For Sale.” Rochelle Adams, director of Yukon River Protectors, and other Alaska Native advocates urged potential investors to stay away. “My whole entire life, the Gwich’in people have stood to protect these lands,” she said. “Alaska is not for profit. Alaska is our homeland.”

Inside, where their voices could not be heard, Dunleavy — who has close ties to the fossil fuel industry and has called natural gas a clean and renewable fuel — praised the project over a catered salmon lunch. Secretary Wright interjected. “The president loves energy. He gushes it. His personality is energetic, but he loves the industry and the role energy plays in the world.” Wright later told Grist that federal loan guarantees for the gas line were “quite likely,” and he hoped to quadruple Alaska’s energy production in the next decade. “It’s about people and math,” he said. Attendees were given pins proclaiming, “I ♥️ Fossil Fuels.”

Glenfarne declined interview requests but claimed in an emailed statement and public meetings that the pipeline will ease Alaskans’ energy bills — a point disputed by local utilities. They plan for the project to unfold in stages, beginning with 765 miles of pipeline from the North Slope to Cook Inlet, to serve the state’s domestic needs. This delays the expense of an export terminal and a large gas treatment plant on the North Slope. “It can be independently financially successful,” Adam Prestidge, president of Glenfarne Alaska, said at a recent event. Though the company has declined to provide any details, the Alaska Gasline Development Corp. previously projected this first phase would cost at least $11 billion.

Critics say without exports, the gas line would effectively run 90 percent empty, losing its economies of scale. “Pipelines never just go from A to B,” Wight explained. “They are the linchpin in a vertically integrated value chain. You can’t just break it off into little pieces and pretend that they’re not connected.”

For all the recent talk of energy security and eager buyers, even Trump’s support cannot change the economics that have long conspired against the pipeline, Persily said. “I used to get a lot of calls from reporters” asking about such plans, he said, but they eventually got tired of hearing him say the idea was “still bullshit.”

North of the Arctic Circle, Sarah Furman bounced along the muddy ruts of the Dalton Highway in a friend’s battered pickup, swerving through cranberry and willow blazing gold in the day’s last light. The Koyukuk River churned nearby, swollen from floods that had swallowed stretches of the road, which was built to reach North Slope oil fields. Parking under the rusty supports of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, Furman explained that rising waters and restless ground threaten the state’s existing energy infrastructure and put new construction at risk.

Average annual temperatures in northern Alaska have already climbed more than 6 degrees Fahrenheit and could rise at least 8 more by the end of the century. Thawing permafrost is damaging the oil pipeline by destabilizing its supports. (Similar instability contributed to the collapse of an oil tank in Siberia in 2020, creating a catastrophic spill.) Scientists and state officials have identified dozens of landslides creeping toward the pipeline with no proven way to stop them, and the state has already had to reroute the Dalton Highway. In places like the snow-dusted Atigun Pass, a narrow cleft through the Brooks Range, steep terrain and shifting ground leave engineers with few options for shoring up a system that still carries nearly half a million barrels of crude oil each day.

The Alaska Gasline Development Corp.’s proposed route roughly parallels the Trans-Alaska Pipeline across the northern portion of the state, though scientists warn the ground beneath it could reach “a highly unstable state” as temperatures continue to rise. “The permafrost is thawing so rapidly that there’s no way they’re not going to face challenges in construction,” said Furman, who tracks the impacts of climate change on interior Alaska as co-executive director of Fairbanks Climate Action Coalition.

The project’s environmental review noted the risk of thawing, Furman said, but didn’t adequately consider other long-term climate hazards, like flooding or landslides. Nor did it account for what exporting natural gas would do to global greenhouse emissions, an oversight that led environmental groups to sue the Department of Energy in 2020. The Biden administration agreed the assessment was insufficient but reaffirmed its approval in 2023.

For many Alaskans, that felt like a betrayal — proof that even as the ground beneath them literally shifts, those in power refuse to acknowledge the risks. Among them is Linnea Lentfer, one of eight youth suing the state to stop the project. Alaska’s constitution requires that natural resources be sustainably managed for the benefit of all; the plaintiffs argue that exporting natural gas violates that duty and “would substantially increase climate pollution and devastating impacts of climate change.”

For Lentfer, who was raised on food her family caught or harvested, the lawsuit is about protecting a vanishing way of life. Her childhood was spent hunting on skis and fishing in rivers alive with coho, the demands of each circling season grounding her in “part of something so much bigger.” Now the salmon don’t always return, and the hills around her home in Gustavus often remain snow-free. “To see those things change in my lifetime — I’m 21 — is incredibly scary,” Lentfer said. “It knocks you down to wonder what it means to live a life here, because I can’t imagine anything else.”

Ironically, Glenfarne could receive up to $7 billion in federal carbon sequestration credits through the project. Prudhoe Bay gas contains carbon dioxide, which must be removed before it can flow through the pipeline. This requires an expensive carbon removal and sequestration facility — something the Alaska Gasline Development Corp. promises will be “the largest carbon capture plant in the world.” The project’s environmental review noted Glenfarne could also get paid for the captured carbon, which oil companies could use to expand production in the Kuparuk River Field by injecting it to extract more oil. This would compound the project’s adverse climate impacts.

Natural gas also contains methane, a greenhouse gas far more potent than carbon dioxide. It has a habit of escaping the infrastructure it passes through, through both intentional venting and leaks across the supply chain. Those emissions, researchers say, far exceed what the government officially counts. Still, in March, Trump overturned a Biden-era fee that would have made oil and gas producers pay for excess methane emissions.

The sheer scale of Alaska’s gas line sharpens those concerns: Once completed, the system could carry 3.3 billion cubic feet of liquified natural gas each day. The export terminal alone will annually produce four times more emissions than every car currently in the state, a point former Federal Energy Regulatory Commission member Richard Glick made in his dissent when that agency approved the project in 2020. “Rather than wrestling with the Alaska LNG project’s significant adverse impacts,” he wrote, “today’s order continues to make clear that the commission will not allow anything to get in the way of its rushed approval.”

Daniel Skarzynski splashed through puddles as he checked on his dog team, the animals circling and restless in the damp. A rumble of diesel engines carried over from Coldfoot Camp, a way station on the Dalton Highway halfway between Prudhoe Bay and Fairbanks, where truckers fuel up as they haul supplies to the oil field.

Skarzynski, a trapper and musher, often spends weeks in the wilderness. When he’s back in Coldfoot in the sturdy canvas tent he lives in, he follows the pipeline talks from afar. He often joins the online public meetings, and watches as officials usually go into an executive session to make decisions that could remake the North Slope behind closed doors. The way Skarzynski sees it, “A lot of companies just treat the Alaskan government as kind of suckers.” For years, he noted, the president of the Alaska Gasline Development Corp., Frank Richards, has been the state’s highest-paid employee. He earned $488,000 last year — almost three times what Governor Dunleavy made. “To be fair,” said energy policy analyst Ben Botteger, “he gives excellent Powerpoint presentations.”

Richards declined to be interviewed and denied a public records request for communications around the project’s timelines or costs, citing his authority to create confidentiality agreements.

Last year, the state legislature appeared to tire of pouring money into the gas line and cut the state corporation’s budget. It also ordered an independent review to determine whether the pipeline would have “a positive economic benefit.” Though the Development Corp. is a public entity spending state money, a 2018 audit by the legislature found “no evidence” the board approved or even knew about its biggest contracts. Another analysis found that if Alaska had invested the money it gave the agency, every resident could have received $1,800. In the spring of 2024, as some of the project’s permits neared expiration, the corporation’s board conceded that, barring an infusion of private funding, “we have instructed AGDC staff to initiate the work required to shut down and either sell Alaska LNG project assets or put them in storage.”

Then came the deal with Glenfarne. Many Alaskans believe a pipeline will usher in another boom. Others aren’t so sure. “They tout it as job creation, but it’s all outside guys,” Skarzynski said, using Alaskan slang for anyone from beyond the state.

Inside Coldfoot Camp, some of the truckers gravitating toward the wafting smell of diner coffee were more concerned with safety. Some worry that the added traffic will make the Dalton Highway — a remote, minimally maintained two-lane road — even more treacherous. It has already grown more dangerous as inexperienced drivers flock to the Willow project, an oil lease the Biden administration approved. Additional transit will increase wear and tear on a highway the state already struggles to maintain, an expense lawmakers have said the budget can’t absorb.

Out on the highway, a wolf slipped between a lull in traffic, its motion fluid as it ghosted through the brush. Up the road in Wiseman, year-round residents Sean and Mollie Busby worry about the safety impacts of the additional traffic and what that will mean for their business, where guests from around the world come to their hand-built cabins beneath the northern lights. A gas compression station is slated to be built nearby, its round-the-clock glare threatening to illuminate the nighttime sky.

What draws some visitors here is nostalgia for one of Alaska’s most valuable resources: the enduring myth of boundless opportunity. For over a century, it’s fueled the rush for gold and then for oil. “Everybody talks about how things used to be up here,” Skarzynski said, recalling stories about miners traveling on the frozen Koyukuk River as early as September. Today, there are spots where it doesn’t always freeze; every year, Alaskans die falling through what used to be dependable ice roads. “I wouldn’t travel along parts of the Koyukuk any time now, you know?” he said. The lure of a simpler, untamed world has left the land haunted by its own legend. The ground is thawing. The oil checks are smaller. Even the last frontier has its limits.

Thirty years ago, bumper stickers started appearing on pickups in Fairbanks and beyond as oil prices tanked. Jobs had vanished, foreclosures had spiked, and almost half of the state’s banks had failed. At the time, taxes on oil production provided 90 percent of the state’s general fund. Those stickers appeared on tailgate after tailgate, offering a simple plea: “God, please give us another boom. We promise not to piss this one away.”

Those weathered stickers still appear from time to time, providing a cautionary tale. The cost of building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline ballooned tenfold to $8 billion in part because there were no incentives to control costs. Companies were allowed to deduct their construction expenses, passing them on to the state and refiners transporting oil through the system. By failing to regulate these shipping fees, Alaska forfeited about $80 billion — to say nothing of what’s been lost to rock-bottom oil production taxes. “What those oil companies did with shipping tariffs was the greatest heist in Alaska’s history,” said Wight, the environmental historian.

At the time, the state had few sources of income and was facing bankruptcy if the oil pipeline didn’t move forward. Legislators tried to exert more control over the project and secure an ownership stake in it, but relented when oil companies threatened to walk away. Producers promised jobs for Alaska Natives to drum up support, but the targets weren’t met for decades.

The parallels to what’s happening today are clear. Utilities in south-central Alaska face dwindling natural gas supplies from Cook Inlet, which has historically provided most of the state’s supply. The inlet still holds extensive gas reserves, but they are unprofitable to extract. As a result, utilities are warning the region could face rolling blackouts by 2027, a supply crunch that Glenfarne CEO Brendan Duval said “can only be solved, in the long term, [by] the pipeline.” The current scramble for energy echoes the leverage companies held over the state during its original oil boom 50 years ago.

Local utilities say the gas line won’t solve the affordability crisis. Without foreign buyers — who so far have not signed binding purchase contracts — the pipeline will be overbuilt and the costs paid by state ratepayers. Even the Alaska Gasline Development Corp. concedes that “Alaskans only require a small portion” of the system, which calls for an oversized, and uncommon, 42-inch pipe. “A more economical solution,” the Alaska Utilities Working Group wrote, “would be a smaller diameter pipeline” — though even that would likely be more expensive than importing natural gas. Richards told state officials last fall that the pipeline is “significantly overbuilt for Alaska’s needs,” but a redesign would require another round of environmental review and permitting. “Current natural gas demand in Alaska simply does not support a pipeline project,” the working group cautioned.

What’s more, the proposal does not include the cost of a 30-mile spur that would bring liquified natural gas from the pipeline to Fairbanks, Alaska’s second largest city. The cost of the additional infrastructure is not included in the Alaska Gasline Development Corp. estimates of future energy prices. If the spur were built, residents would still have to pay home connection fees and replace home furnaces, for which Wight said his family was quoted $40,000.

Even the region’s gas utility seems skeptical. Elena Sudduth, general manager of Interior Gas Utility, said most of Fairbanks’ gas came from Cook Inlet, carried by pipeline to a liquefaction plant near Anchorage, then trucked north. In 2025, the utility switched to trucking North Slope gas to Fairbanks. A spur line could eventually replace that operation, but “it hasn’t started, and we needed a plan,” she said, adding she’d be shocked if gas flowed, as the governor promised, by 2028.

She also said an independent economic analysis funded by the Development Corp. assumes a rapid shift of 90 percent of the greater Fairbanks area’s energy demand to gas — including power generation — even though most of its power plants run on other fuels. “These are existing assets,” Sudduth said. “Gas would have to be cheap enough to justify new capital investment.” If the report’s assumed energy prices did prove accurate, she says it would be “transformative for the economy, and for Fairbanks, and we are all for it.”

In the meantime, as the state teeters on an energy crisis, state Senator Bill Wielechowski noted that Trump has cut more than $1 billion for Alaskan renewable projects, including wind and solar projects near Fairbanks and Anchorage. Wielechowski said this leaves Alaskans vulnerable to volatile energy price hikes, in what he called a “hostage situation.”

“You’re basically holding a gun to your own head, saying you’re going to be forced now to develop fossil fuels at whatever price companies want to charge you,” Wielechowski said. “It’s time for Alaska to stop giving our resources away.”

At the mouth of the Kenai River on a dim fall day, Cook Inlet takes on the color of raw steel. Pale backs suddenly arc across the surface as two belugas surface, their plosive exhales punctuating the drum of rain. Only around 300 of these genetically distinct whales remain, making them one of the world’s most endangered marine mammals.

The gas line, which would cross under Cook Inlet, would pose new risks to both the belugas and the waters they depend on. Even noise from preliminary surveys — not to mention construction, dredging, and ship traffic — would impair their ability to hunt and communicate.

Ecological impacts would unfold all along the project’s route, from the North Slope, where the infrastructure could impede caribou migration and potentially hasten population declines, to the Gulf of Alaska, where tankers will harry the critically endangered North Pacific right whale. A final environmental impact statement warns that the pipeline’s construction and operation would cause “adverse effects on federally designated critical habitat and a number of federally listed threatened and endangered species.” Regardless, the project received the last federal permits it needed in early December. The National Marine Fisheries Service will allow the project to kill or injure 10 percent of Cook Inlet belugas — which the coalition says is a population-level threat. In comments to the agency, Chief Gary Harrison of the Chickaloon Village Traditional Council wrote that for the whales’ survival, “the margin for error is effectively zero.”

Cook Inlet itself adds to the risk. The waterway surges and sinks with tremendous force, creating some of the largest tidal ranges in the world — leading to a history of industrial accidents. In 2017, one of its natural gas pipelines shifted, striking an unseen boulder that eventually created a hole. Methane poured into the water for more than four months. Federal and state agencies argued over who had the jurisdiction to treat the gas as a hazardous material, and whether the owner could be compelled to shut off its pipeline. Ben Botteger, who covered the debacle for the local newspaper, said the incident “opened up a bunch of questions we’ve pretty much subsequently ignored.”

Among them is who will pay for the cleanup and removal of the gas line and its infrastructure once it reaches the end of production, which Alaska law requires. When the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was built, companies were required to set money aside to eventually decommission it. So far, there haven’t been any public estimates of what remediation of the gas line will cost, a bill that will likely add up to billions of dollars. Senator Wielechowski has pressed the company for answers, warning that without firm commitments, taxpayers could be left paying to clean up accidents or abandoned infrastructure.

It’s a familiar worry in Alaska, where the fossil fuel industry’s influence has so often eclipsed the oversight meant to prevent collateral damage. As Vic Fischer, one of the men who drafted the state’s constitution, once explained, oil men used “economic power to buy the allegiance of elites and many ordinary citizens, until it displaced democracy with its own corporate form of government.”

This kind of influence could now put the state’s finances at risk. Alaska holds a 25 percent stake in the joint venture overseeing the project, and state Senator Jesse Kiehl says it’s unclear whether that could obligate the state to cover cost overruns or unexpected liabilities. The gas line’s $44 billion price tag is more than a decade old; since then, steel costs have increased 66 percent while labor is up 46 percent. Glenfarne hired a consultant to update cost projections in May ahead of its final investment decision, but has no plans to disclose those figures.

In mid-December, Governor Dunleavy announced a bill to slash property taxes on the project by 90 percent, meaning state and local governments would lose hundreds of millions of dollars of revenue. Mayors of boroughs who would be impacted told the Anchorage Daily News the governor did not consult them, and they raised concerns about breaking even with the project’s costs to road maintenance and other municipal services. An independent consultancy recently told the legislature property tax changes were needed to make the project viable. It is owned by a company that intends to invest in the gas line. Even prior to this proposal, lawmakers warned the state’s generous construction tax write-offs for participating companies will strain its already fragile finances.

Whether Alaska’s gas will attract buyers remains an open question. “We’ve already committed over half of the LNG volume from this project to buyers in Japan, in Korea and Thailand, and Taiwan, because they recognize that this is a fantastic project,” said Adam Prestidge, president of Glenfarne Alaska, at a recent public meeting. He said President Trump is “making sure other countries are committing to buy LNG.”

But there are no public and binding purchase agreements. Unlike oil, liquefied natural gas requires long-term commitments. Investors typically take an equity position and agree to a lengthy “take-or-pay” arrangement, meaning they commit to buying or paying for a set amount of gas regardless of market prices. In July, Trump announced that Japan was joining the project; Japanese officials later denied this. Glenfarne cites $115 billion in “interested parties” as buyers, yet neither Japan nor South Korea have signed binding agreements to buy gas — and Seoul has said a $100 billion pledge it made this summer for American gas is not specific to Alaska. A South Korean official told the Financial Times that the U.S. hadn’t provided any information on pricing and said the country wouldn’t have considered the project absent federal pressure. In December, Glenfarne lauded a deal with South Korean steel manufacturer Posco to purchase a million tons of gas annually, though industry trade publications describe the agreement as “tentative.”

Meanwhile, a wave of liquified natural gas development is expected to flood global supply by 2030, including from export projects in British Columbia that are closer to completion and share Alaska’s proximity to Asian markets. In a blunt assessment, independent energy market firm Rapidan Energy Group warned that investors “could incur substantial financial losses” and said the Alaska project is what happens when “politics overrides commercial logic.”

In the absence of committed buyers, the federal government has stepped in. The official export credit agency of the United States federal government has said it will provide financing through its “Make More in America Initiative,” and the Trump administration has floated the idea of the Pentagon buying gas for Alaska’s bases — though that alone would account for a fraction of the project’s capacity.

At the pipeline’s source, Pantheon Resources — the small U.K. firm expected to provide the domestic gas — has not finalized a sales agreement, leaving the project without a guaranteed supplier. Early exploration results have proven disappointing, and Persily argues its existing fields probably cannot meet long-term pipeline needs. Kiehl noted that while plenty of gas reserves exist on the North Slope, major operators don’t appear to be investing any significant resources toward producing for the gas line. “If an oil and gas company sees an opportunity to make a profit, they will pursue it,” he said.

The economic questions could shake markets far beyond the state’s borders. The U.S. is now the world’s largest LNG exporter, largely financed through heavy borrowing. Some experts are starting to ask whether the sector is a bubble, leaving the investors funding them in serious trouble. According to one recent report, if the gas industry’s credit quality declines due to physical climate risks and faltering demand, “we might see more securitized debt packaging similar to the 2008 mortgage crisis.”

Even if the Alaska project never materializes, however, Glenfarne stands to benefit handsomely. By acquiring its intellectual property, permits, and engineering work, the company now has leverage in future partnerships, negotiations, or access to federal support. The company is now working with the private gas utility Enstar, for example, to develop plans to import liquified natural gas to Alaska in a project that duplicates alternative utility plans, driving up costs for ratepayers, while laying the groundwork for their export facility. As the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis wrote in a public comment about LNG export terminals, “Insiders can skim off just a percent or two in fees and bonuses and walk away rich … even if their project isn’t successful.” Glenfarne can profit from this deal without ever laying a mile of pipe.

On a blustery October night in Nikiski, a small town on the Kenai peninsula, the power was out but the sales pitch carried on. Inside a packed community center, lights powered by generators illuminated glossy renderings of the export terminal proposed for the outskirts of town — flawless, gleaming, and a long way from real.

More than 100 residents came to hear from Glenfarne’s team, which hadn’t initially planned to take questions. The crowd, however, had many. Would the rerouted highway cut across their property? Would their wells stay safe? How many locals would get work? Prestidge said the company recently convened 200 contractors in Anchorage — three hours and a world away.

Many in the room had proudly built careers in the inlet’s oil and gas industry, like Robin Bogard, who worked for 16 years at the Agrium production facility, which converted natural gas to nitrogen fertilizers. For decades, Nikiski faithfully sent liquified natural gas from Cook Inlet to Japan, never missing a shipment. Bogard had been enthusiastic about a gas line since the 1970s. But Glenfarne’s pitch — and a look at its numbers — left him unconvinced. Lowering energy bills sounds nice, he said, “but hope is not a business plan.”

The pipeline has become a mirror, reflecting an enduring faith in a future powered by fossil fuels. It hearkens back to a time when deals were struck behind closed doors and entire economies bent to the will of a few. “It creates this paradox: what we want life to be and where life is headed,” said Lentfer. She knows the challenges that come with filing a climate lawsuit but still imagines raising children as she was — rooted in the land, even if that home is inexorably changing.

As the meeting wound down, wind whipped off the inlet, rattling the dark windows of a town that has been waiting half a century for the next boom to arrive. It bore surf against rusting platforms and whistled past dormant pump houses. The gas line that could transform these quiet cliffs into a bustling terminal, Wight said, “is the longest running Alaskan dream outside of immortality.” Who will be left to pay for the dream when it finally comes due?