If you haven’t heard, Fix recently launched a cli-fi writing contest. We are over-the-moon excited about it. Fiction writers have a knack for creating compelling, perception-shifting windows into alternate worlds and making complex issues approachable — and personal. That’s exactly what we hope to do with Imagine 2200: Climate fiction for future ancestors.

Anyone (even you!) can submit a short story that envisions our path to a cleaner, greener, and more equitable world. We’ve enlisted a jaw-droppingly impressive panel of judges to read the best of the submissions and choose the 12 we’ll publish in a digital collection this summer. (Did we mention there’s cash involved? The grand-prize winner will pocket $3,000, with $2,000 and $1,000 going to the second- and third-place winners respectively.)

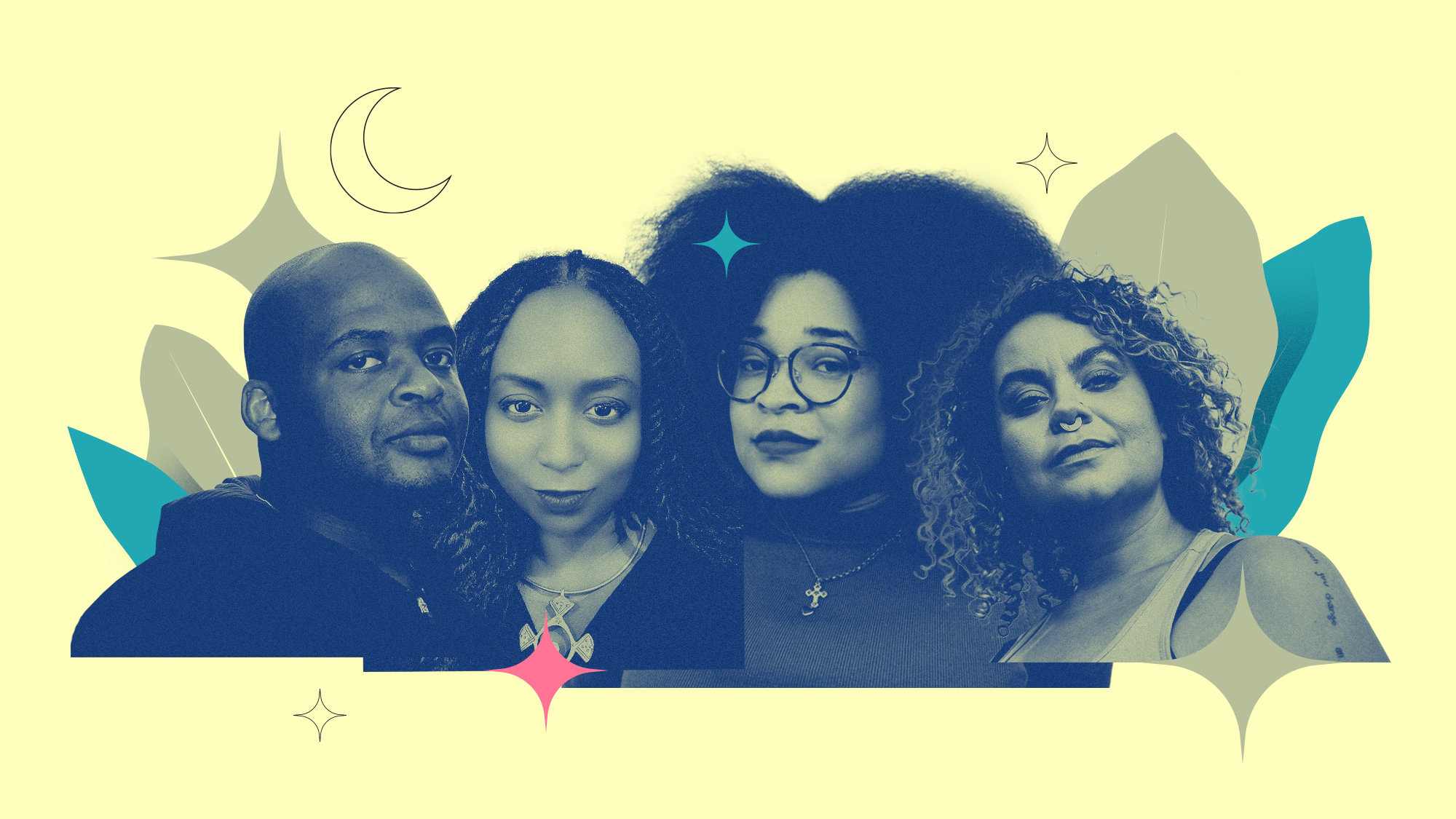

Sheree Renée Thomas, Adrienne Maree Brown, Morgan Jerkins, and Kiese Laymon know their way around a narrative. Between them, they’ve written more than a dozen books — memoirs, novels, and essay and short story collections that explore race, culture, family, nature, and even time travel. And they’ve earned heaps of awards and distinctions for their outstanding work.

Fix caught up with our illustrious judges to talk about their approaches to climate fiction and other literature, the impact they think it can have, and what they’re hoping to read in Imagine 2200. Their comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Sheree Renée Thomas is a fiction writer, poet, and editor in Memphis. Her works include Nine Bar Blues, Sleeping Under the Tree of Life, and Shotgun Lullabies. Thomas was recently named editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Storytelling is one of the oldest forms of communication. It touches things in us, and it stays in our memories longer, I believe. Art is more vital in these days than ever, as we’re living through a pandemic.

Climate change has been something I have explored in my creative work for a while. It has directly impacted my own family here in Memphis. We used to be able to fish in the Mississippi River, and now that’s not advised. I’m in the middle of a fight to keep an oil pipeline from going through a historic community in South Memphis called Boxtown that was created right after emancipation. People are rallying around that. In the short stories for this contest, I trust that writers are going to look around them and pull up the very real things that are happening in our world right now. Ideas are great, but if you don’t tell me in a way that makes me care about and invest in what happens to the characters, then it’s just so-so.

I think it’s an amazing time for speculative-fiction writers, and it’s so good to see Afrofuturism embraced by a larger community. I’m here for it. So many wonderful writers are adding their voices to the genre. And lots of other creative projects are coming from it — films and animation and graphic novels — and people are using these as case studies for social change in real time. I see it as an open-source code that’s constantly evolving and changing, and that’s the way it should always be.

My advice to writers who are considering submitting: Read your work aloud! It’s an incantation. And it puts the story in a different light. You’ll find some of the missing beats, you’ll find areas you have an opportunity to expand upon. Oh, and send it in on time!

Adrienne Maree Brown is a scholar and activist in Detroit. She is the author of Emergent Strategy and Pleasure Activism, and co-edited the anthology Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction from Social Justice Movements.

I think it’s difficult in this moment to tell a story about our future that is neither dystopian nor utopian — that’s not some scenario in which we get everyone into a lush green garden and it’s all good, but it’s also not Mad Max Fury Road. Interdependence is going to have to change our trajectory as a species, and I think fiction has to be the place where we try out what that looks like.

I’m very critical of the fiction I write. Every time, I’m like, “I was aiming for Toni Morrison and I landed at The Bachelorette.” But I had good intentions! “The River” is the story that I think comes the closest to cli-fi for me. It is a story about the Detroit River responding to gentrification and climate injustice and fighting back. For me, when I think of climate fiction, when I think of climate justice, I think about partnering with the land. Partnering with the water. Partnering with the air. Partnering with the forces of change that our planet represents — not saving it.

We are heading toward a future in which Black and brown people are the majority in the U.S. — and we are heading toward a future in which climate crisis is guaranteed, based on the behavior we’ve already engaged in. So we are called to be prophets in this moment.

When we did Octavia’s Brood, most of the contributors were non-fiction thinkers, movement thinkers, scholars, academics. And they wrote some of the most prescient, brilliant fiction. So, my advice to writers: Don’t think that it’s outside of the realm of your possibility. We write because we have a critique of the current circumstances. So if you want to change things, here’s the invitation.

Morgan Jerkins is an author and editor in New York City. She wrote This Will Be My Undoing and Wandering in Strange Lands. Her debut novel, Caul Baby, will be released next month.

In this contest, I hope to see stories that focus on Black and brown populations. I hope to see stories that highlight all of the -isms and phobias that have debilitated our society and how they will metastasize with climate change. I also hope people will explore how climate affects us not just on the grand scale, but the granular.

I grew up in New Jersey. This year, I visited my mother for Christmas, and we followed a tradition that she used to follow with her parents: going around the neighborhoods to see the Christmas lights. She noted that it was different this time because there was no snow. That was the first time I thought that not only is the climate changing, perhaps our traditions are changing, too. And tradition, especially familial tradition, is something I have explored in my writing.

I think cli-fi is a flexible term. For me, it means possibility. I think about Octavia Butler’s work — some of the stuff she’s written, we’re living it now. For those of us who read a lot, we understand the power literature wields. Who’s to say writing isn’t a prophecy? Who’s to say that whatever somebody is writing right now might not be the basis for policy proposals in the future?

Ultimately, I hope these stories reveal how our imaginations can help build a better reality. We need to be imaginative about the future and what it could be — not only to serve as a guiding light, but to serve as a balm for these current, difficult times.

Kiese Laymon is a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Mississippi. He is the author of Heavy and How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. His debut novel, Long Division, will be reissued later this year.

My first novel is about Black kids in Mississippi who go into the woods in 2013, 1985, and 1964. (There’s a time-travel element.) One thing I was exploring was environmental degradation. The woods change from green, to brown, to eventually no longer existing. I wanted to subtextually ask the reader, “What does it mean when these green spaces that rural Black children play in disappear? And why? Does it have anything to do with how close these communities are to power plants and incinerators?” I didn’t make that explicit, but I was trying to show it in the way the kids kept asking why the forest was changing.

I think cli-fi as a genre foregrounds climate’s relationship to people, places, things, and culture. I’m really excited about the elastic way this can be interpreted. In Imagine 2200, I hope people write stories from the points of view of things other than humans. I’m interested in post-human stories — maybe somebody wants to write a story from the POV of the climate itself, or a pine tree, or a crawdad, or a possum. I hope people are as creative as possible, and that they use this opportunity to write a story they might have needed permission to try.

I also hope people who don’t think they mess with sci-fi or cli-fi will be encouraged to apply. Sometimes I’ve had the most success while writing a genre that I didn’t particularly like and wanted to renovate. If you are tired of cli-fi, if you are tired of writing, fam, use this as an opportunity to expand, explore, destroy, and wonderfully, beautifully, tenderly build.

Feeling inspired? Submit your story to Imagine 2200 by April 12! Together, we can fix the world with fiction.