In Billy Guevara’s neighborhood on the northeast side of Houston, people get nervous when it rains. Old ditches strain under the deluge of a Gulf storm, and mud and water fill the streets. Guevara, a writer who is blind, once had a seeing-eye dog that would navigate around the ankle-deep puddles and lingering muck. “It became unsafe because I ended up having to walk almost in the middle of the street,” he said. “It stays there for days.”

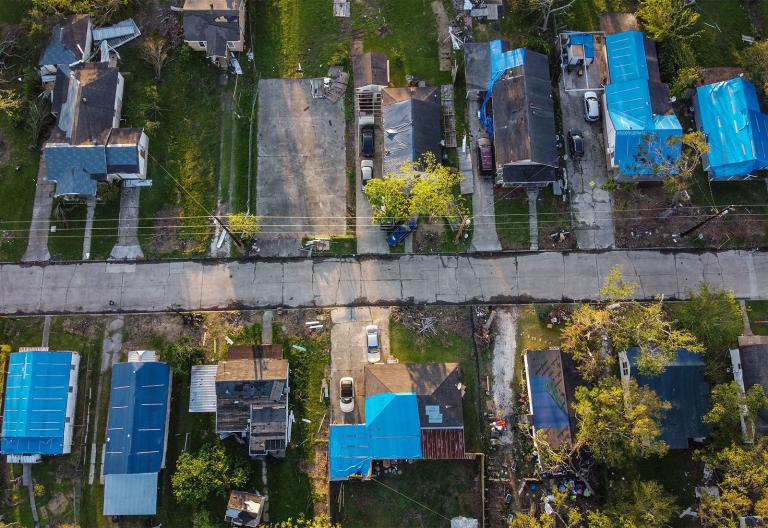

Guevara is a member of the Northeast Action Collective, a community group pushing the city and Harris County for equitable investments in flood control. He says drainage in his neighborhood of Lakewood is outdated: “It cannot handle the type of rain that we see now.” When Hurricane Harvey hit in 2017, homes across many of northeast Houston’s Black and Hispanic neighborhoods flooded, swamped under 30 inches of rain in what was the country’s costliest disaster that year. Under the rush of water, one of the walls in Guevara’s home began to bulge out.

Years after Harvey, little aid has made it to the people of Houston. The federal government budgeted some $9.3 billion so that communities could not only rebuild, but also better prepare for the next storm. But city and regional governments have delivered little of those funds, and a state agency’s “competition” has held back aid that the Department of Housing and Urban Development designated for post-Harvey mitigation, money which would have helped upgrade drainage systems. As a result, low-income communities like Guevara’s have been left out of much-needed infrastructure improvements.

Without their fair share of aid, communities struggling to rebuild will be just as vulnerable when the next storm comes, advocates say. These obstacles also expose weaknesses in HUD’s recently created mitigation program, which aims to help reduce risks from future climate disasters.

Hurricane Harvey flooded nearly 100,000 homes in Houston, inflicting $16 billion in residential damage. Guevara had growing mold, damaged floors, and a leaking pipe. With a small FEMA grant and the help of local nonprofits, he was eventually able to repair his home.

But today, thousands in Houston still wait for funds to rebuild. Disaster recovery aid through HUD often comes with significant delays since the program is ad hoc, requiring Congress to approve spending for each disaster. In 2018, HUD allocated $5 billion to Texas through its Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery program, which is designed to help with long-term rebuilding.

HUD had sent the money to the Texas General Land Office, or GLO, the state agency run by George P. Bush, grandson of former President George H.W. Bush, which is responsible for public lands, mineral rights, and the Alamo historical site, as well as disaster recovery. In turn, the state agency gave Houston’s share to the city, but didn’t entirely relinquish control, continuing to oversee how funds were doled out. The city and state agency squabbled over how to run things, and when HUD began an audit of the program, the fight escalated, eventually making its way to the Texas Supreme Court. In October 2020, the feud ended with the state seizing control of the program.

All the while, many residents remained in dangerous living conditions, stuck in homes with leaking roofs and mold-filled walls, said Becky Selle, a co-director at the grassroots group West Street Recovery. It’s unclear whether those waiting will ever get assistance. In January, when HUD published its audit, only 297 of nearly 8,800 applicants had received funds. (The state has until August 2025 to use the money.)

The struggle to access federal aid extended far beyond homeowner’s assistance. Harvey was among the first disasters for which HUD’s Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery program made money available for mitigation projects like widening bayous, upgrading water and sewer systems, or buying out flood-prone homes. This marked a major shift: While disaster recovery funds had to be tied to damage from a specific disaster, the $4.3 billion mitigation fund could be used to improve conditions, making communities safer.

Houston and Harris County accounted for more than half of Texas’ damage from Hurricane Harvey, but when the GLO released its spending plan in December 2019, city officials feared Houston wouldn’t get its fair share.

Because there weren’t enough funds for every proposed project, the state’s land office set up a competition in which jurisdictions would apply for a slice of the $1 billion in the initial round. HUD identified 20 mainly coastal counties, including Harris County, that were most distressed by Hurricane Harvey and would be eligible for funds. The land office then expanded the list, adding counties that fell under the umbrella of the original FEMA disaster declaration in 2017. That more than doubled the list with more rural, inland counties like Milam, 200 miles from the coast.

When results from the competition came out last May, Houston didn’t get a cent. The city’s requests for $470 million worth of projects, like flood control in the majority-Black neighborhoods Sunnyside and Kashmere Gardens, were rejected. So was the $200 million watershed improvement plan for the flood-prone Halls Bayou, which is surrounded by some of Houston’s poorest neighborhoods. “For the State GLO not to give one dime in the initial distribution to the city and a very small portion to Harris County shows a callous disregard to the people of Houston and Harris County,” Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner said in a statement at the time.

Instead, funds largely went to smaller, whiter, inland towns. They went to drainage upgrades in Rockdale, a two-hour drive northwest of Houston, and sewage improvements in Nixon, a small town outside San Antonio that emerged from Harvey unscathed and sheltered evacuees fleeing the storm. “The more that we’re giving this money to inland counties and jurisdictions, we are actually taking away from where we truly need the money and where the money was originally intended to assist communities,” said Julia Orduña, the southeast Texas regional director at Texas Housers, a low-income housing group.

After the snub, the city of Houston hoped for a second chance when the Houston-Galveston Area Council, a regional council spanning 13 counties, planned to deal out its own pool of the funds. But in February, the council granted just 2 percent of its $488 million to the city, which represents around 30 percent of the council’s population.

According to the council, Houston and Harris County didn’t need much more than that because the GLO planned to grant the county a direct payment of $750 million — a promise only made after the first competition received intense criticism. But that wasn’t a fair consideration, according to Mayor Turner, since that grant had yet to be approved.

Last June, the Northeast Action Collective and Texas Housers filed a civil rights complaint with HUD, alleging that the GLO discriminated against Black and Hispanic residents. In a recent letter sharing the findings of its investigation, the federal agency sided with the organizations, saying the competition “substantially and predictably disadvantaged minority residents, with particularly disparate outcomes for Black residents.”

A major issue, according to HUD, was that the state agency split the competition in two. Half the funds were reserved for counties that the federal government had identified as hardest hit by Harvey — where Black and Hispanic residents were most likely to live — while the other half went to more rural, inland counties included on the state’s expanded list, which tended to be whiter.

At minimum, HUD required that half of the funds would go to communities on its list of hardest-hit counties. While the state agency met that requirement, dividing the competition in two also meant awards to those counties would be capped at 50 percent. But those counties represented 90 percent of the population in the entire competition, amounting to much less money available for Black and Hispanic residents.

After the winners were announced in May 2021, GLO spokeswoman Brittany Eck backed the results in a statement to the Houston Chronicle. “It is important that Texas inland counties are resilient as they provide vital assistance to our coastal communities during events such as asset staging, evacuations, sheltering, and emergency response/recovery,” she said.

The competition favored smaller communities. A flood control project in Houston’s mostly Black and Hispanic neighborhood of Kashmere Gardens, HUD’s letter explained, would have helped 8,845 residents. But Houston’s total population is 2.3 million, so the project scored less than 1 out of 10 points because it would help only a small percentage of residents. On the other hand, the city of Iola applied for a wastewater project that all 379 of its residents would gain from. It scored 10 out of 10, and the project was funded.

In an email to Grist, Eck accused the federal agency of “blatant political theater.” She said GLO has complied with HUD’s requirements, and now it’s being faulted for not “going above and beyond” to benefit even more minority residents than it already has. Eck said the land office is appealing HUD’s findings.

“GLO did not engage in discrimination, and HUD’s allegations amount to nothing more than unlawful attempts to ‘second-guess’ GLO’s open and transparent competition process, which was approved by HUD,” Eck said.

When the state agency’s spending plan was still a draft, Madison Sloan, director of the disaster recovery and fair housing project at Texas Appleseed, a public interest justice center, sent a letter detailing concerns that its scoring system would divert money from the hardest-hit areas. “I don’t want to deny that communities all over the state need mitigation,” she said. “But when you look at where the damage was, where people are most vulnerable, it is the coast. What this represents is a missed opportunity to do some really large-scale, meaningful mitigation on the coast that’s going to protect a lot of people.”

These problems aren’t limited to Houston. Along the coast, other cities hit hard by Hurricane Harvey, like Beaumont, Corpus Christi, and Port Arthur, lost out in the competition. In Port Arthur, where the poverty rate is twice the national average, floods propelled by nearly 50 inches of rain devastated the housing stock. Decades of underinvestment have eroded residents’ ability to recover from disasters, said Michelle Smith, marketing director at the Community In-Power and Development Association, Inc., an environmental justice group in the city. Some decided to leave Port Arthur entirely because “they had nothing to come back to,” she said. So it stung when the city’s proposal for a $97 million drainage project was rejected.

Without these funds, communities that were poorly equipped for Harvey are just as vulnerable to the next storm. “This is an ongoing thing,” Smith said. “With each hurricane, we continue to suffer because we’re not able to recover. The little bit that we can salvage is then taken away again and again and again.”

Sloan thinks the whole situation exposes fissures in HUD’s mitigation program. It’s largely up to states to decide how to divvy up funds, but studies are needed in advance to ensure fair distribution, she said. That doesn’t just benefit the vulnerable; it could make the coast, as a whole, more resilient.

“Funding to areas where vulnerable people of color live is going to benefit plenty of white people, plenty of higher-income people who also live in those areas,” she said. “In this case, in general, equity means everyone wins.”

After backlash followed the first competition, the state’s land office announced that it would give the remaining funds to regional bodies like the Houston-Galveston Area Council to distribute — the same entity that offered Houston a minuscule amount of federal aid. “The GLO’s solution to not doing a second competition was pushing the responsibility to local jurisdictions,” said Orduña, who felt the new plan does not rectify HUD’s allegations of discrimination.

There will be other storms to come, and Congress will eventually allocate more money to rebuild from them. When that happens, Billy Guevara, of the Northeast Action Collective, worries all the talk and reports will have been just that. “That’s our biggest fear,” he said. “Being overlooked again.”