This story is produced by Floodlight, a nonprofit news site that investigates climate issues.

When she saw the drilling rig go back up, Kim Feil started closing windows.

She didn’t want a repeat of 2013, when she experienced nosebleeds after natural gas drilling began at the site just a quarter mile from her home in Arlington, Texas, in the Barnett Shale. A 2019 study found people living between 500 and 2,000 feet of fracking sites have an elevated risk of nosebleeds, headaches, dizziness or other short-term health effects.

For five years after fracking surged in the late 2000s, Feil blogged almost every day and regularly attended council meetings. She warned neighbors of potential health effects, including studies finding higher risk of asthma attacks, from chemicals used during the drilling process. By 2014, as natural gas prices plummeted, fracking activity began to slow down.

Recently, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and gas prices skyrocketing, that economic equation changed again. Profits from natural gas drilling surged to new heights. The Railroad Commission of Texas, which oversees the oil and gas industry, reported the most active gas well permits in seven years.

This past summer, as the price of oil and gas hit historic highs, the city of Arlington quietly approved nearly a dozen permits for new gas wells near the homes of its residents without holding any public hearing, leaving Feil and other members of the community without a chance to comment or protest the activity.

That’s a change from earlier activity, when companies including Total Energies and XTO started fracking in the Barnett Shale, a geologic formation containing trillions of cubic feet of fossil fuels. The shale lies under the heavily populated Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, home to more than 7 million people. Drilling brought heavy industry and noise, air and water pollution to Arlington, an otherwise typical suburban city of 400,000 nestled between Fort Worth and Dallas.

So far, despite the recent permit activity, only one drill site is active now — the Truman drill site half a mile from AT&T Stadium, home of the Dallas Cowboys and near Feil’s home. In November, Feil watched as crews for French energy giant Total’s subsidiary, known as TEP Barnett or TEEP Barnett, returned to erect a new rig. She’s already reported a rotten egg smell to a city inspector.

“I’m just at the mercy of which way the wind blows,” Feil said.

New gas wells approved behind closed doors

City staff say public hearings for new wells are unnecessary because most of the new permits are in existing drill zones approved by previous City Council members.

As long as companies drill within one of those approved zones, their permit request can be greenlit internally by city staff without a council vote or public hearing. Seventeen of Arlington’s 51 permitted gas drilling sites have an approved drill zone, according to city data. A majority of the drill zones were approved in 2013 or earlier.

Arlington calls the process “administrative approval.” Under this protocol, a natural gas company’s only obligation is to notify property owners who live within 1,320 feet that drilling will begin soon, said Susan Schrock, a city spokesperson. The city declined to make officials available for a phone interview.

According to records reviewed by Floodlight News and Fort Worth Report, historically, the city did not frequently use the administrative approval process. Over the past 10 years, Arlington used the process 81 times, or an average of eight per year. By contrast, in 2022, the city approved 17 wells administratively.

Of TEP Barnett’s current 31 drill sites in Arlington, five are in established drill zones, according to city data.

Over the past three years, TEP Barnett applied for 62 new gas wells in Arlington, per data from the Railroad Commission of Texas — 87 percent of those were at sites with established drill zones and eligible for administrative approval.

Leslie Garvis, a spokesperson for TEP Barnett and Total Energies, said the company has not built any new drill sites in Arlington since acquiring existing facilities from Chesapeake Energy in 2016. Drilling new wells at existing sites allows the company to further develop the area’s natural gas resources without increasing TEP Barnett’s footprint, she said.

While TEP Barnett has not expanded its physical footprint, the company has increased its number of applications for new wells. In 2022, TEP Barnett applied for 25 more new gas well permits in Tarrant County than they did the year before, according to data from the Railroad Commission.

Since drilling in the Barnett began, many residents have supported the expansion of natural gas drilling as an economic opportunity. Property owners sign lease agreements with gas companies allowing them to collect royalties from gas revenue. In Arlington, the drilling boom put the city in a position to donate $100 million in royalties to a foundation funding neighborhood, nature and other charity projects.

But, without public hearings, Ranjana Bhandari said there’s no opportunity for residents to ask city officials or Total questions about potential drilling activity and associated pollution. Bhandari serves as executive director of the environmental advocacy organization Liveable Arlington, which has become one of the most vocal opponents of fracking in the city and helped galvanize dozens of residents to show up at council meetings about drill sites.

“The way that I see this move by the city is a move to remove public hearings as part of the permitting,” Bhandari said. “Nothing can replace that public forum — it’s a time honored requirement. Look at what they’re doing. They’re sticking something so insanely polluting and obtrusive in your backyard.”

Limited visibility, limited impact

The renewed focus on administrative approval has limited Liveable Arlington’s ability to lead visible opposition campaigns to fracking, which previously stalled efforts to expand drilling.

Many permitted drill sites are concentrated in lower-income neighborhoods, often with a higher concentration of renters and people who don’t speak English as their primary language. Landlords are entitled to receive notice of new drilling activity while many renters remain in the dark, Bhandari said. These residents don’t have the time or access to follow what’s happening, she added.

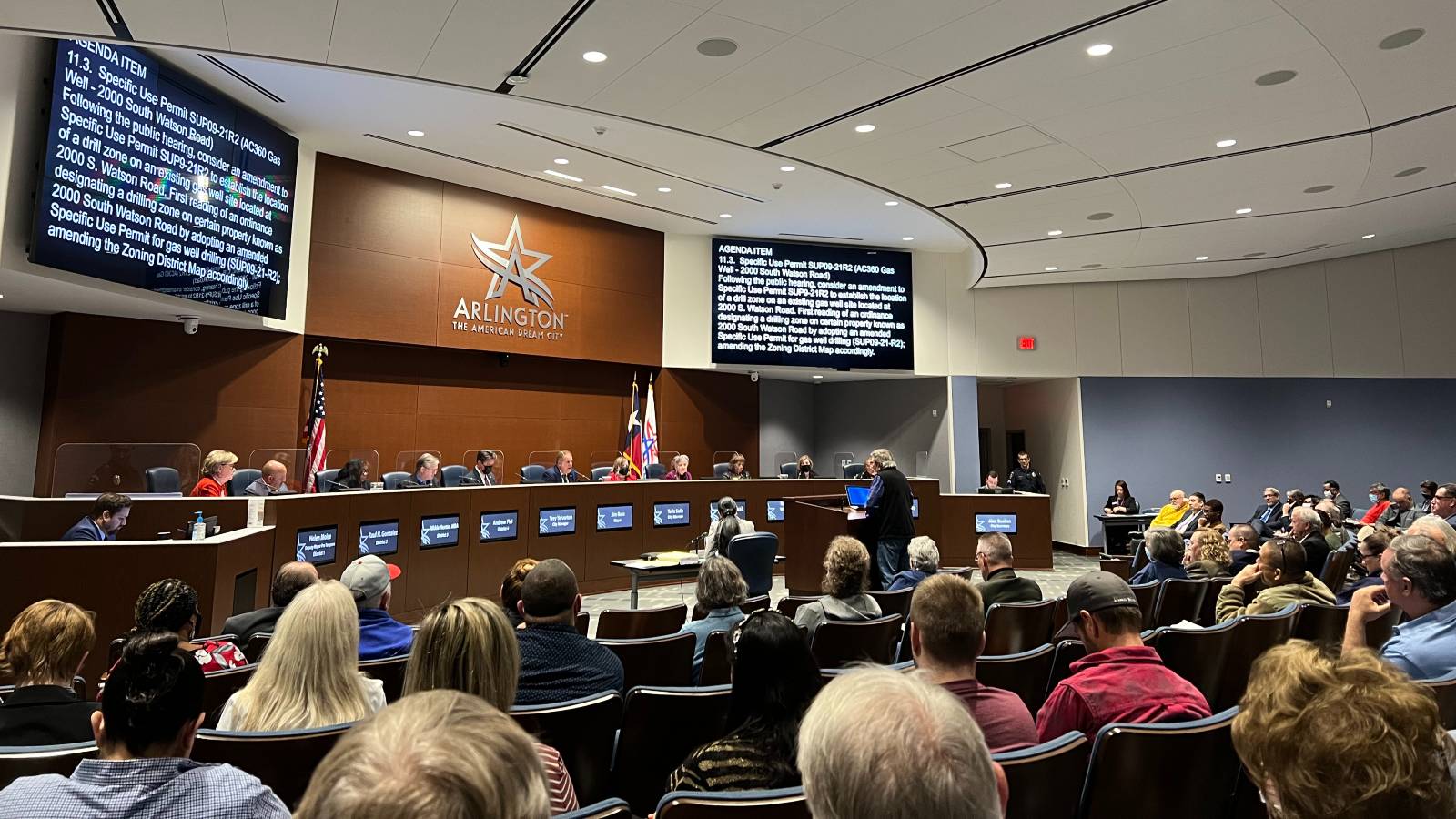

Liveable Arlington’s success has come from turning out crowds at public hearings to pressure local officials into denying new drill permits. In January 2022, Arlington City Council members denied a permit for three new wells next to a daycare center after Liveable Arlington and the daycare owner filed suit against the city. Two years earlier, Arlington earned national headlines for voting down gas drilling near a community of color as leaders reckoned with the city’s record on racial equity.

Katheryn Rogers, a volunteer who tracks natural gas permits for Liveable Arlington, said the hearings serve as a chance to educate residents and prove there is community opposition to new drilling.

“We do get wins,” Rogers said. “If we’ve got a full chamber and we’re up there saying, ‘OK, scientists say this about drilling,’ that’s educating them as to what’s fixing to happen in their backyard. Council also needs to be held accountable for what they’re voting for.”

In the absence of public hearings, Liveable Arlington volunteers try to fill in the gaps through door-to-door canvassing, an email newsletter and an online permit tracker.

“All the illnesses, the property damage, the quality of life issues they’ve faced,” Bhandari said. “All of that gets aired at a public hearing. And that’s what they are trying to suppress.”

‘Unusual’ obstacles to obtaining public records

As the city is turning more to a quieter administrative approval process for the permits, it also appears to be limiting or delaying access to public records. These days, open records requests about permits that used to be granted in a few days have taken weeks, if not months, to be filled. It’s a marked shift from the relationship Bhandari used to have with city officials, many of whom know her from more than a decade of activism.

“What I’ve seen is that the city is becoming more combative and trying to avoid turning over information if they’re able to,” said Jayla Wilkerson, a lawyer representing Liveable Arlington. “But it’s not unusual for a government entity to work harder to hide information as they see how that information is being used — which is unfortunate because that’s the purpose of public information law.”

Molly Shortall, an attorney for the city of Arlington, did not respond to specific questions about the city’s policies toward gas drilling records. Arlington has always complied with the Texas Public Information Act and requested decisions from Attorney General Ken Paxton’s office when they thought records contained information that is not open to the public, Shortall said.

Information that is not subject to public disclosure includes personnel records, pending litigation, trade secrets and real estate deals. The city’s priority is to release open information to the public efficiently and promptly, Shortall said. Large amounts of data related to gas wells in Arlington are currently posted online and freely viewable on the city’s website, she added.

In one instance, city lawyers referred Liveable Arlington’s request for drill zone maps to the attorney general’s office for a ruling. The city tried to claim that the information was proprietary — an argument that wouldn’t have held up in court, Wilkerson said.

TEP Barnett had 10 business days to provide evidence to explain why the information was proprietary. When the company didn’t respond, the attorney general’s office ruled that Arlington’s claim wasn’t valid. However, the attorney general suggested that the city could instead withhold the information on the grounds that it contained information about “critical infrastructure.” Releasing the map, the office said, could pose a terrorism threat.

Arlington followed the attorney general’s advice and denied the release of the information to Liveable Arlington, setting a possible precedent for future requests. The Attorney General’s Office did not respond to request for comment.

“This struck me as unusual in lots of ways,” Wilkerson said. “The city didn’t initiate [the security threat] part of the claim. It was the state government that said, ‘Hey you have another option here as a way to hide information.’”

Bhandari fears that this pattern is already in motion — and could be here to stay.

“It’s been a terrible shift in how the [government] is treating its own residents,” Bhandari said. “And I want to know why. Why can’t they honestly tell us why they’re doing what they’re doing?”