This is the second in a two-part series about oil and gas emissions in the San Joaquin Valley originally published by Capital and Main. Read the second story here.

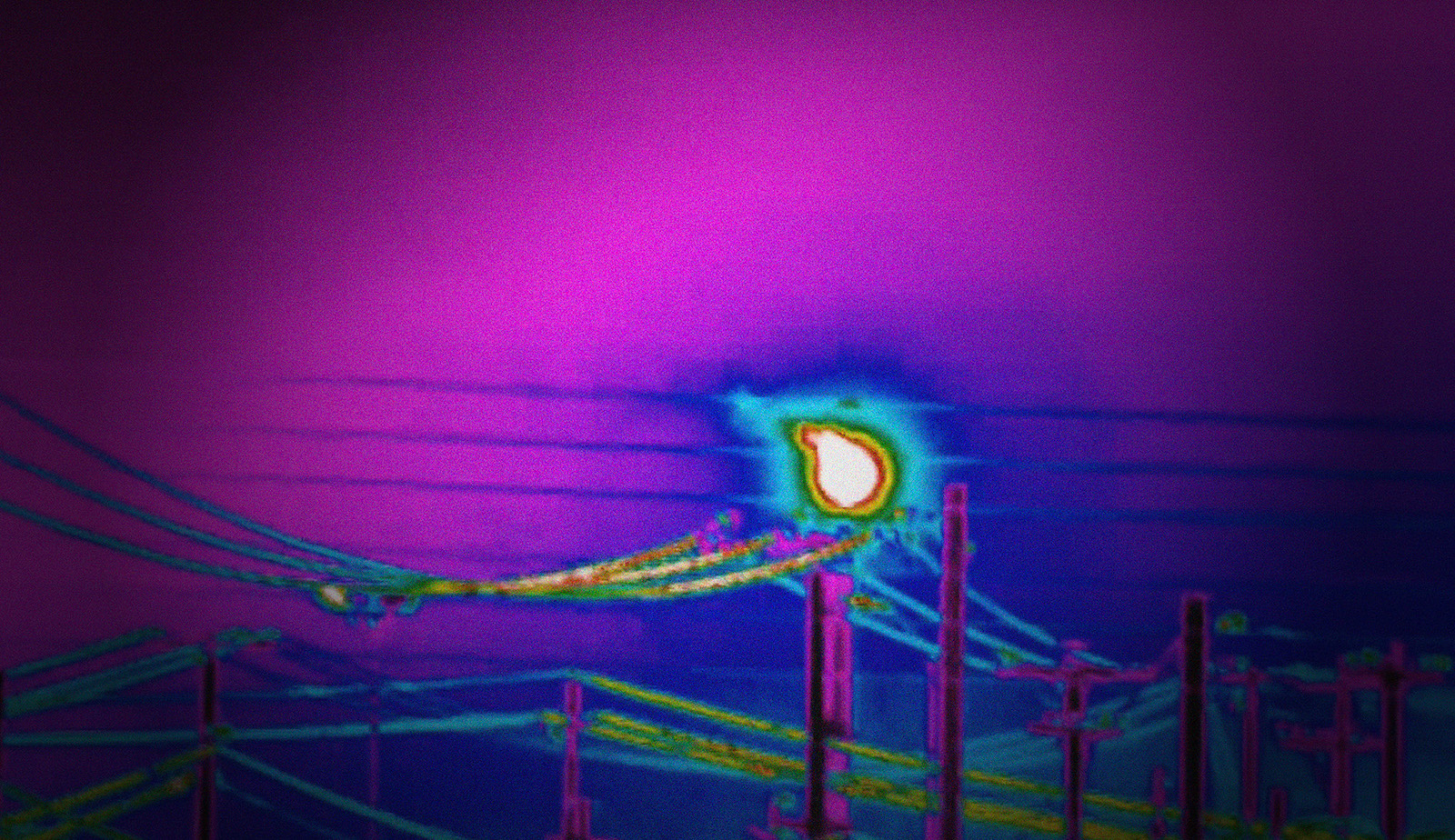

Amid the desert of western Kern County — the beating heart of California’s oil and gas industry — the Elk Hills gas power plant and refinery stand out as a mighty structure of steam, steel piping and turbines, surrounded by pumpjacks bobbing for oil. From half a mile away on a public road, Kyle Ferrar of the FracTracker Alliance and Andrew Klooster of Earthworks use an optical gas imaging camera equipped to capture emissions invisible to the naked eye. The camera detects hydrocarbons coming from two flare devices, which appear as constant, furious streams of pollution into the sky.

These emissions can include methane, a greenhouse gas vastly more dangerous than carbon dioxide that is leaking widely into the atmosphere from oil and gas facilities across the world. They can also contain volatile organic compounds, including hazardous air pollutants and hydrocarbons that react with nitrogen oxides, another common industrial pollutant, in the sunlight to form ground-level ozone, the main ingredient in lung-damaging smog.

The Elk Hills facility, owned by California Resources Corporation, is responsible for plumes of methane, according to data collected by a joint partnership between NASA and the state involving the use of remote sensing aircraft. State records show that in 2019, the gas plant emitted 198 tons of organic gasses, including hydrocarbons like methane, contributing to a total of at least 998 total tons of organic gasses and 120 tons of nitrogen oxides emitted that year in the San Joaquin Valley from oil and gas equipment owned by the same company.

The facility has received 20 enforcement violations for leaks over the last five years from the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District, the local regulator that oversees compliance with state and federal air laws. A state audit also identified more than 500 methane leaks at the Elk Hills plant in 2019 that were eventually repaired. However, regulators with the local air district told Capital & Main and Type Investigations that the flare emissions are acceptable under the company’s permits.

But the district’s methods of mitigating pollution could be underestimating the impact of emissions from industry, according to residents and experts. And the gas refinery is far from the only source of major pollution in the area, which is home to many of California’s busiest oil and gas fields. Some are among the dirtiest in the world, spewing climate-warming emissions as they pull fuel from the ground.

A local emissions trading system, mandated by federal law in areas that fail to meet standards for air quality, is supposed to incentivize companies to reduce overall pollution beyond what is required by regulations by rewarding them with offset credits. Companies bank credits with the San Joaquin Valley air district, and can “cash in” credits to build more polluting infrastructure while claiming net pollution isn’t rising. Every cashed-in offset credit balances out pollution that is released into the San Joaquin Valley’s air. At least on paper.

As of March 2022, there are banked credits representing 43,300 tons of 10 different pollutants that have been offset. The oil and gas industry has banked almost half of these credits, and California Resources Corporation, or CRC, has banked the most, with credits representing 9,558 tons as of July 2021. The company cashed in credits worth 8.9 tons of volatile organic compound emissions annually to offset the flare pollution.

Spokesperson Richard Venn said CRC “follows emissions reduction protocols to comply with local and federal regulations,” including the use of emissions reduction credits for “a maintenance project related to our gas processing plant at Elk Hills,” adding that the flares comply with regulations and any violations are quickly addressed.

After a state regulator found major issues with San Joaquin Valley’s emissions reductions credits system two years ago, including poor bookkeeping and overcounted emissions reductions, advocates based in the area are raising concerns about high levels of pollution that may have been greenlit by regulators, and expressing doubts about regulators’ proposals to improve the system.

Jesus Alonso, an organizer with Clean Water Action and a member of the public advisory workgroup on the credits system, now sees the program as a failure. “The polluters were allowed to continue to pollute with the promise of clean air, and that’s not what the community members got at all,” Alonso said.

The air district, meanwhile, says the offsets system has contributed to permanent emissions reductions within the 25,000 square miles of the San Joaquin Valley, which has some of the worst air pollution in the country and is designated as an “extreme nonattainment” area for ozone under federal regulations. The EPA notes that the area is particularly hard hit because smog precursors and particulate matter that get trapped in a mountain basin come not just from industry but also agricultural burning, wildfire smoke, pesticides, landfills, industrial dairy farming, and heavy diesel trucks.

The air district says it’s committed to maintaining “an effective permitting system that allows for protection of public health and strong economic growth,” according to spokesperson Jaime Holt.

Yet it’s under pressure from the industry and federal regulators to keep the struggling emissions credits system humming along. Catherine Garoupa White, executive director of the Central Valley Air Quality Coalition and a member of the emissions reductions credits public advisory group, says regulators seem more concerned with giving industry what it wants than with protecting public health. “From my encounters with them, they are more focused on figuring out how to enable industry,” White said.

In the valley, emissions from major oil and gas polluters can harm people’s health directly by contributing to smog, and indirectly by contributing to climate change, which exacerbates illnesses and health problems.

The small community of Buttonwillow sits a few miles from several of the largest oil and gas fields in the state, a blip of homes, a school, and a couple of restaurants along Highway 58. Driving west past agricultural fields, one encounters a large sign underneath looming transmission towers and the distant Temblor Range that proclaims Buttonwillow “The Heart of California Agriculture.”

Outside of his grandmother’s wooden home, a chubby cheeked 4-year-old named Cesar struggles to catch his breath as he excitedly talks about dinosaurs and school. His grandmother, Adela Carranza, tends to Cesar and his three younger sisters on the porch, as she explains that he uses both an inhaler and a nebulizer to manage severe asthma.

“When I take him to school, they’ll send him back because he can’t breathe,” Carranza said in Spanish. His air “catches in his chest.”

Up the street, 22-year-old Armando Guzman also wheezes as he talks about growing up in Buttonwillow, where his parents settled after coming to the U.S. from Mexico as children.

Guzman came down with pneumonia two years ago and then started exhibiting severe symptoms of coccidioidomycosis, or Valley Fever, an incurable fungal infection of the lungs that comes from spores in the dirt of the southern San Joaquin Valley. Infections are on the rise here as intense rainy seasons following periods of drought allow the fungus to thrive in the soil. It’s then blown around by the wind.

“Like right now, it hurts when you breathe,” said Guzman, who worked in a nearby oil field for six months until his lungs couldn’t take anymore. “It’s like trying to breathe into a bag, like you’re breathing your own air.”

Respiratory issues rank among the top concerns for the 900,000 residents who live in the sprawling county, according to its public health department. Asthma plagues Kern and surrounding counties like Madera, Kings, and Fresno. In addition to severe ozone, particulate matter in the air is among the worst in the country.

The San Joaquin Valley air district trumpets progress since the 1980s. In response to questions from Capital & Main and Type Investigations, it said stationary sources — regulator lingo for industrial facilities — account for only a fraction of greenhouse and air toxic emissions, while mobile sources such as diesel-powered trucks account for the majority.

One state assemblymember, a former emergency room doctor from Fresno named Joaquin Arambula, introduced legislation this year, now under consideration by the State Senate, that would bring the local air district under closer supervision by state regulators. “It’s unacceptable that we have national air quality standards that haven’t been met since 1997, and I believe that the San Joaquin Air District can do more,” Arambula said.

Arambula’s legislation succeeded in the State Assembly despite the powerful role the oil and gas industry plays in California. Republican Assemblymember Vince Fong and Democratic Assemblymember Rudy Salas of Kern County have taken $195,896 and $266,529 from the industry, respectively. Fong voted against the legislation in the Assembly and Salas didn’t register a vote on it. The bill is still pending in the Senate, where Sen. Shannon Grove of Kern County has taken $259,875 from the industry and leads a Bakersfield company that helps staff the local oil and gas sector.

Fong and Grove didn’t respond to requests for comment. In a statement sent via email, Salas said he supports the air district’s “efforts to restore clean air and improve the health and safety of our Central Valley families,” and would consider supporting the bill if it comes up for a vote in the Assembly again in August.

While there are several sources of pollution in the valley, the oil and gas industry’s political influence may obscure the true extent of the harm linked to its emissions. Major companies like Chevron and Aera Energy, a joint venture of Shell and Exxon, are contributors to schools and local civic organizations and events, and the industry’s revenues represent a significant portion of the tax base for Kern County and several others in the valley.

The emissions reductions credit system’s flawed implementation is an outgrowth of this sprawling influence over the regulatory process, critics say. For years, oil majors banked millions of credits to use for future expansion. Problems with the system began coming to light two years ago.

The systemic problems center on millions of nitrogen oxide and volatile organic compound credits, the two pollutants that create smog. The vast majority of these credits currently in circulation were generated in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. The idea was that industries would adopt innovative pollution controls to reduce emissions in order to earn credits.

Over the years, state and federal air quality standards improved, which under federal rules would have wiped out the emissions reductions value of older credits because they had to signify pollution cuts “above and beyond” what current regulations require.

But an agreement between the EPA and the San Joaquin Valley air district in the 1990s allowed the district to maintain the value of the credits at the time they were issued — meaning old credits generated under less strict regulations could retain full value. The district just needed to show its system resulted in equivalent emissions reductions as under federal rules.

It did this in part by claiming emissions reductions from oil equipment that was no longer operating, and from agricultural equipment that switched from diesel to electric engines. These methods, separate from the credit system, eventually accounted for hundreds of tons of emissions reductions the district used to say it was in compliance with federal law.

The California Air Resources Board, or CARB, the state agency overseeing all 35 local air districts, audited the system and found that the district overestimated reductions and kept poor records. In one case, the district claimed 528.5 annual tons of volatile organic compound pollutant reductions, based upon estimating the impact of shutting down six petroleum storage tanks. The true value should have been zero because they hadn’t operated for nine years.

In response, the district committed to reexamining the way it counted emissions reductions and over the last two years essentially erased millions of pounds of reductions value from nitrogen oxide and volatile organic compound credits. It also assigned staff to oversee efforts to correct the system full time, and began holding public meetings with industry and environmental representatives.

Environmental justice advocates welcomed the reforms but say they don’t go far enough, and fear the district will eventually revert back to using dubious accounting.

“We’re looking for ways to identify new emissions reductions credits to allow for [industrial] projects to keep happening,” according to Errol Villegas, the permit services manager for the air district’s central region, in a recent public meeting.

At a meeting with community representatives in April, several people asked what regulators could do about pollution approved with faulty credits, arguing many projects should never have been approved. The San Joaquin Valley air district has said it doesn’t have the capacity to investigate past permitted projects.

The EPA has also suggested as much. “You can’t go back and start from the beginning and do this really quantitatively,” said Meredith Kurpius, assistant director of the Air and Radiation Division for the EPA Region 9 overseeing the air district, at the meeting. She added that the audit’s true value was ensuring “in the future we have a more transparent program.”

In response to questions, the air district said that the emissions credits system is one of several methods to limit harms to human health, and that companies must also implement the best available technology to control pollution and ensure it won’t “create a significant health risk” to the surrounding community and vulnerable populations. Companies are also directed to offset the “worse-case potential scenario” for pollution.

Last November, the Biden administration proposed a new Clean Air Act rule that would further restrict methane emissions from oil and gas operations, estimating that it could eliminate millions of tons of methane and volatile organic compound pollution over the next 12 years. But if the air district once again allows companies to use old credits, that could blunt the impact of the new regulations.

Regulators have created a “false dichotomy” pitting jobs against public health, said Sasan Sadaat, a senior research and policy analyst at Earthjustice and a member of the emissions reductions credits public advisory group.

“We need to confront this reality that economic growth that depends on increased pollution can no longer be the thing we reach for,” Sadaat said. “We can’t just try and create crediting programs that allow us to pretend like we could actually permit new pollution in this region with the belief that some other programs or projects or credit generating opportunities will offset it. They won’t.”

Jesus Alonso, also a member of the public advisory group, said clean air advocates in the valley see litigation against the air district as a potential avenue for redress. They could, for example, file a civil rights complaint alleging the permitting program discriminated based on race. Air pollution in the San Joaquin Valley has disproportionately harmed people of color, and the Biden administration has pledged to overhaul the EPA’s civil rights enforcement office.

But suing may be a last resort. “First what we’re going after is being able to actually quantify how badly the air district messed up,” Alonso said, “and finding ways to balance that out.”

Funding for this story was provided in part by the Fund for Investigative Journalism. This story was produced in partnership with Type Investigations, where Aaron Cantú is a reporting fellow.