Global corporations like Amazon and Mercedes-Benz want us to think they’re serious about taking on global warming. But independent analysts say their climate pledges can’t be taken at face value.

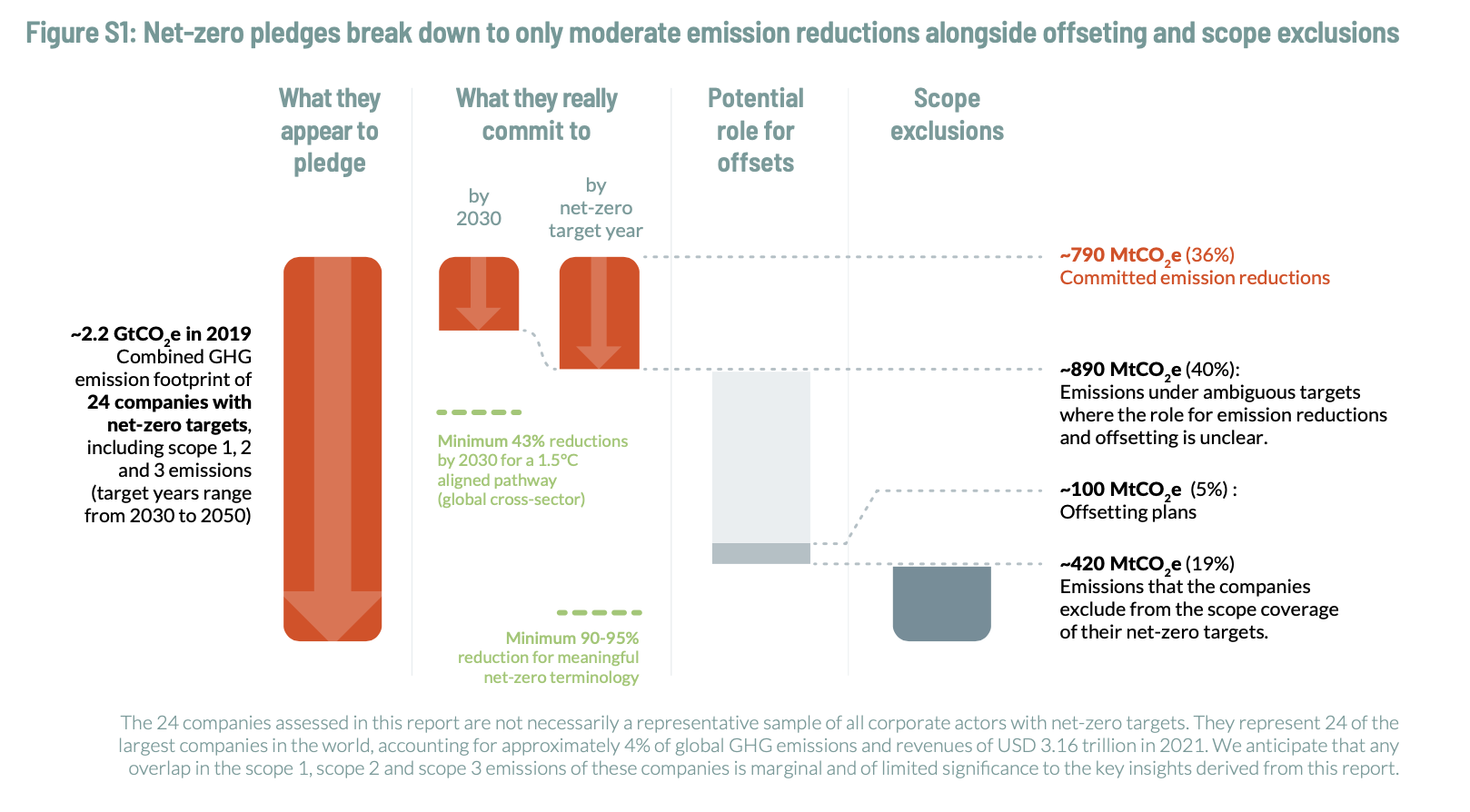

Climate commitments from 24 of the world’s largest self-proclaimed green companies are “misleading” and “wholly insufficient” to keep global temperatures from rising above 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), according to a searing report released Monday by the NewClimate Institute and Carbon Market Watch, two European environmental organizations. These two dozen companies have pledged to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, but their cumulative commitments cover only 36 percent of their total greenhouse gas emissions — in large part due to their reliance on spurious carbon offsets or their failure to address huge swaths of the emissions from their supply chains. For 17 of the companies, the authors highlighted an “inadequacy or complete lack” of actual plans to substantiate their net-zero pledges.

Companies are engaging in an “aggressive communications campaign” to state that they will be net-zero, said Gilles Dufrasne, Carbon Market Watch’s lead on global carbon markets, during a media briefing last week. “But that is simply not what they’re pledging. … I would categorize that as greenwashing.”

The report authors looked at climate commitments from some of the largest international companies that are part of the Race to Zero campaign, a global initiative that commits institutions to a credible pathway toward limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C. The researchers identified eight of the world’s highest-polluting sectors, including automotives, electronics, and fashion retail, and selected three companies from each sector. These companies are outspoken about their decarbonization commitments, which in some cases they have prominently advertised.

Overall, the report paints a bleak picture of corporate climate responsibility. It found 15 of the 24 companies’ climate pledges to be of “low or very low integrity,” eight to be of “moderate integrity,” and zero to be of “high integrity,” based on a range of factors like their commitment to long-term emissions reduction. Several pledges, including ones from Amazon and American Airlines, rely on misleading carbon credits linked to forests that are unlikely to sequester carbon for more than a few years. Others, like a 2040 carbon neutrality pledge from the French grocery giant Carrefour, simply omit so-called scope 3 emissions — the emissions from the products companies sell to customers. These emissions may represent more than 90 percent of a company’s climate pollution (98 percent, in Carrefour’s case).

Companies in some of the most polluting sectors — like the car company Volkswagen and the meat behemoth JBS — had no credible plans to change their business models or diversify away from activities that are inherently emissions-intensive. Others, including PepsiCo and Nestlé, have built hype around a practice called “insetting,” which involves offsetting emissions that originate within their supply chains. (For example, a company could close one of its factories and claim this cancels out the emissions from another one.) The NewClimate Institute and Carbon Market Watch said this is an “illegitimate” concept, and even more poorly regulated than most offsets.

Just one company — Maersk, the maritime freight giant — had a pledge deemed to be of “reasonable integrity,” as it was one of the only ones whose net-zero target covered 90 percent or more of its overall emissions footprint. Pledges from fast fashion company H&M, the automaker Stellantis, and the cement and concrete manufacturer Holcim also covered 90 percent or more of their carbon emissions, but those pledges performed more poorly on transparency or reliability.

Thirteen of the companies named in the report responded to Grist’s requests for comment. H&M, Mercedes-Benz, and Volkswagen said they welcomed the report for recognizing their sustainability initiatives and, along with Amazon, Ahold Delhaize, Foxconn, Samsung, and Thyssenkrupp, reaffirmed their previously stated carbon neutrality targets. Carrefour and Walmart disagreed with the report’s methodology and said it mischaracterized their emissions goals. Maersk responded to criticisms about its use of biofuels, saying it sees them as a transition fuel until alternatives are available at scale, and said its emissions targets are aligned with guidance from third-party verification organizations. Microsoft and Stellantis declined to comment.

Thomas Day, an expert on carbon markets and corporate climate action for the NewClimate Institute and a coauthor of the analysis, emphasized the importance of scrutinizing companies’ short-term emissions pledges, many of which have been “inappropriately” certified by third-party organizations. Almost all of the 24 companies analyzed by the NewClimate Institute have emissions reduction targets for 2030, and 16 of these have been certified by the Science-Based Targets Initiative, or SBTi — a widely respected certification body whose stamp of approval lends legitimacy to private sector climate commitments — but their pledges only a cover a median of about 15 percent of their total climate pollution between 2019 and 2030. This is in contrast to the global emissions reductions of 43 and 48 percent, respectively, that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says is necessary in that time frame to keep temperatures from rising past 1.5 degrees C.

“These companies may be members of voluntary initiatives, but nearly all companies making these pledges are making them in response to consumer and investor pressure,” Day said. “They’re making the case to regulators that they do not need to be regulated.”

In response to Grist’s request for comment, SBTi linked to a seven-page technical statement explaining some differences between the way it evaluates companies’ net-zero pledges and the report’s methodology, including different definitions of carbon offsets.

Eduardo Posada, an analyst for the NewClimate Institute, said the report made clear the need for greater clarity and enforcement of existing consumer protection laws, as well as new rules to keep up with the rapidly-evolving world of corporate greenwashing. As with food that’s certified “organic,” he said, decarbonization claims should be required to meet a list of criteria to prove they’re more than just empty words. The European Union is currently considering a crackdown on greenwashing, and federal agencies in the U.S. are in the process of tightening regulations on emissions disclosures and misleading environmental marketing claims.

Posada endorsed a wholesale ban on terms like “carbon neutral” and “net-zero” in advertisements, since they open the door to ambiguity and questionable carbon offsets. “The terminology is misleading in itself” and is likely to be misunderstood by the public, he told Grist. “‘Zero’ is OK because it means total or near-total decarbonization, but the ‘net’ is where all the tricks go into. Companies can do many things inside of that ‘net’ word.”

“We believe it would be more constructive, more helpful if companies actually committed to reductions instead of these slogans,” he added.

This article has been updated to include a response from Maersk.