Puerto Rico has more medical sterilization facilities per capita than anywhere else in the U.S. and its territories. These plants, where hospital equipment is fumigated before being introduced to the market, comprise a small but essential industry, one that hospitals rely on to ensure they have the sterile equipment necessary to safely treat millions of people each year.

All this sterilization, however, creates its own risks to human health. That’s because about 50 percent of all medical device sterilization in the U.S. and its territories uses ethylene oxide. While the chemical is employed for its unique ability to penetrate porous surfaces and destroy microorganisms without damaging heat-sensitive materials, it is also a potent carcinogen.

In August 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency published a list of 23 commercial sterilization facilities that emit enough ethylene oxide to elevate the cancer risk in nearby communities above the agency’s safety threshold. Four of Puerto Rico’s seven facilities made the list. This clustering of sterilization plants is directly tied to the island’s tax code, itself the vestige of a colonial past that continues to impact the economic futures of ordinary Puerto Ricans — and, in the case of these sterilizers, threaten their health as well.

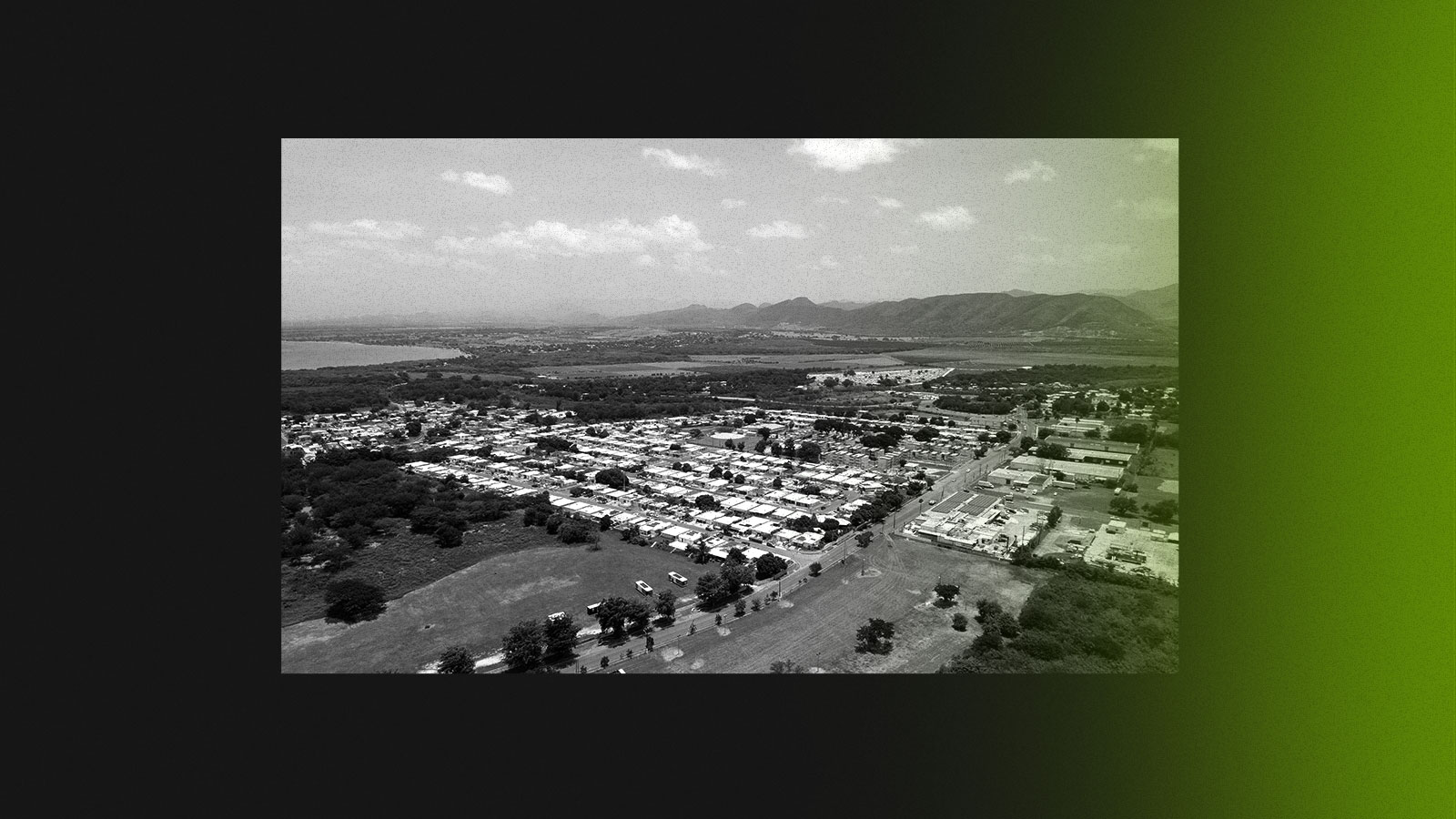

Documents from Puerto Rico’s Department of Economic Development and Commerce, or DDEC, as well as interviews with local officials, show that the agency grants and renews tax incentives to companies even if their operations pose a substantial risk to public health. Steri-Tech, for example, is the most toxic medical sterilizer in all of the U.S. and its territories, exposing residents in the southern Puerto Rican town of Salinas to a cancer risk 1,000 times higher than the level that the EPA considers acceptable. Yet despite its environmental and public health risk record, the company continues to enjoy lucrative tax breaks. Three other medical sterilization companies — Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Customed — have also received tax breaks and were estimated to elevate residents’ cancer risk, according to EPA modeling from 2022.

Puerto Rico’s system of tax incentives traces its roots to the 1940s, when the U.S. federal government began implementing programs designed to move the island away from its agrarian system and to a more industrial economy. The number of Puerto Ricans working in manufacturing steadily increased over the following decades, and in 1976, Congress decided to give the island’s economy a second jolt with a transformative policy known as Section 936. This new section of the federal tax code effectively gave U.S. corporations a complete federal tax exemption for operating in Puerto Rico. Pharmaceutical companies were by far the largest beneficiaries of the policy, flocking to the island to take advantage of the lucrative new tax incentives as well as the relatively cheap labor force and the bountiful aquifers, which provided a source of clean water they could use to manufacture medication.

The emergence of the island as a tax haven transformed both the biosciences industry and Puerto Rico’s economy. According to a 1992 report from the federal Government Accountability Office, for every dollar pharmaceuticals paid to a Puerto Rican worker, they saved $2.67 in taxes that they would have otherwise paid to the federal government. This came out to around $70,000 in tax breaks per worker every year. For their part, Puerto Ricans were promised stable long-term jobs in a sector that would spur economic growth. Indeed, by the mid-1990s, the industry had created an estimated 170,000 manufacturing jobs, a substantial sum on an island of 3.5 million people.

But all this growth came at a cost, one paid neither by the mainland-based companies nor the government that lured them to the island. Puerto Ricans worked the most dangerous jobs in the medical supply industry, risking exposure to toxic chemicals; in recent years, the island’s pharmaceutical operations saw more Office of Health and Safety Administration complaints, accident reports, and health and safety referrals than that of any other U.S. state or territory. A pattern of lax environmental regulation allowed the industry to pollute without substantial repercussions, dumping the toxic byproduct of pharmaceutical production into Puerto Ricans’ air, water, and soil.

After Congress voted to end Section 936 in 1996, citing excessive costs, the Puerto Rican government scrambled to put together a tax incentives policy of its own to keep pharmaceuticals on the island. Over the next decade, it enacted the Tax Incentives Act and the Economic Incentives Act, which were later consolidated in the Puerto Rico Incentives Code in 2019. The four medical device sterilization facilities that the EPA has found pose a significant cancer risk were granted tax breaks under these laws — in some cases as early as 1999 — and continue to benefit from them to this day. According to the most recent report of tax expenses from Puerto Rico’s Treasury Department, tax exemptions for materials and technology used in health services amounted to roughly $38 million through 2022. The report projects that, between 2023 and 2026, the treasury will lose out on an additional $39 million as a result of these incentives.

The DDEC approves tax breaks to companies. Puerto Rican tax laws grant the secretary of the agency the authority to deny applications for economic incentives if it determines that the concession is not in Puerto Rico’s best economic and social interest — a consideration that can include a company’s environmental impact. But in general, companies are only required to prove that they continue to meet fiscal requirements under the island’s tax laws by submitting financial and operational reports annually.

Amarilys Rosario Ortiz, manager of the Air Quality Area in the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, said that her agency does not send the DDEC its reports on environmental compliance, but instead maintains communication with the federal EPA. This suggests that the DDEC may not have critical information with which it could evaluate a company’s environmental impact. According to Peggy Pacheco, an environmental quality specialist who works in the natural resource department’s Inspection and Compliance Division, the agency inspects each sterilization facility roughly every five years, since sterilizers are categorized as a “synthetic minor” source of emissions, despite the high cancer risk the EPA has identified.

Following the approval of the Incentives Code in 2019, every two years the DDEC is supposed to issue a certificate of compliance to those companies who submit the required reports. If compliance reports are not submitted on time or if they are incomplete, the DDEC can fine companies up to $10,000 or revoke the tax incentives. However, this requirement is “not binding” on companies that were grandfathered in under older tax incentive laws, according to the director of the DDEC Business Incentives Office, Carlos Fontán Meléndez.

The DDEC has never revoked incentives on the basis of a company representing an environmental and public health risk for Puerto Ricans, and it insisted that questions for this story about environmental compliance be directed to the EPA instead. According to EPA regional air quality officials, the DDEC is not “delegated to enforce the Federal Clean Air Act or the Regulations for the Control of Air Pollution of Puerto Rico,” which are the prerogative of the EPA and the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, respectively.

Fontán Meléndez said that revoking an incentive following an EPA investigation, for example, would only happen if the federal agency “believes that this violation is irreparable” and orders the closure of the operation. In the case of the sterilization facilities, the EPA finalized new rules earlier this year requiring companies to install controls that reduce the amount of ethylene oxide released. It has not ordered any sterilizer on the island to shut down.

From 2009 up to April 2024, the DDEC revoked 267 tax concessions to manufacturing companies in Puerto Rico. Two of them belonged to Abbott Pharmaceuticals and St. Jude Medical, a company acquired by Abbott in 2016, which uses ethylene oxide for some of its operations. None of these were revoked for environmental noncompliance. The agency said most were revoked for a failure to submit annual reports. Fontán Meléndez said the DDEC has issued fines to some of these companies but would not provide a list or explanation of fines issued, claiming that the agency cannot disclose specific information about taxpayers who have an active tax concession.

DDEC Secretary Manuel Cidre Miranda also said that the Incentives Code “provides that there’s a responsibility to manufacture or address environmental issues responsibly,” and that the law does not need to be amended to better enforce environmental regulations. Medical device companies are already highly regulated, he argued, referring to the rules imposed by federal and state agencies, including the EPA and the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources.

“We’re more focused on those less regulated industries,” said Cidre Miranda. “From my position, I can tell you that I’m pleased with the security standards, with the metric standards that that industry has.”

Meanwhile, of the four companies that the EPA identified as elevating cancer risk with ethylene oxide emissions — Steri-Tech, Customed, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic — only the latter two responded to questions regarding what steps, if any, they have taken so far to implement the corrective actions required by the EPA, and whether they have notified the DDEC of activities related to this.

Medtronic said it has taken steps to add additional pollution control equipment and that it also upgraded facilities in accordance with national emissions standards, although it did not specify which ones. The company added that economic incentives have supported its expansion and that it maintains communication with the DDEC, among other agencies, to address concerns related to ethylene oxide, even though the DDEC does not require compliance information related to the chemical.

Edwards Lifesciences’ senior director of global communications, Howard Wright, said in a written statement that the company completed improvements to its ethylene oxide control system that can eliminate more than 99.99 percent of emissions. He did not say whether the company updates the DDEC on emissions records or corrective actions.

Luis E. Rodríguez Rivera, a professor at the University of Puerto Rico School of Law who headed the island’s natural resources department in the early 2000s, said that the true social cost of medical supply production, including environmental and public health effects, is not adequately considered by agencies like the DDEC. If these factors were considered, he argues, the cost of pharmaceutical products would be higher and the industry’s profits would suffer.

“It’s not unusual that these laws that promote economic development not only don’t internalize environmental impacts of the activities they are promoting, but go further and promote actions that limit the effectiveness of any health or environmental or safety protection that there may be,” he said.