This story was originally published by Honolulu Civil Beat and is republished with permission.

Wesley Yadao, 71, farms five acres of taro in a region of Kauai where generations of families have tended the starchy root vegetable in wet paddies fed by the Waimea River.

His tough-knuckled hands betray the necessity of a strong work ethic, an indelible link to his great-grandparents who planted the first seeds of the family’s taro-farming legacy.

“There’s a lot of memories in this valley,” said Yadao, who produces 900 pounds of taro a week with his wife and occasional help from charter school children.

Demand for the staple crop of the traditional Native Hawaiian diet is growing, farmers say, and about a dozen farms in Waimea struggle to keep up — optimistic circumstances for any food producer.

Yet today’s generation of taro farmers in arid West Kauai worry about the future of a cherished way of life.

A proposed renewable energy project promises to supply up to a quarter of the island’s total power usage by diverting 4 billion gallons of water a year from the Waimea River and its tributaries. Residents who rely on the watershed for fish, to grow much of the food they eat, or for commercial crop production fret about the effects of these diversions on the river’s health.

And while the project envisions promoting agriculture, farmers like Yadao worry that it will be at the expense of traditional practices like his that rely on the natural flow of the river.

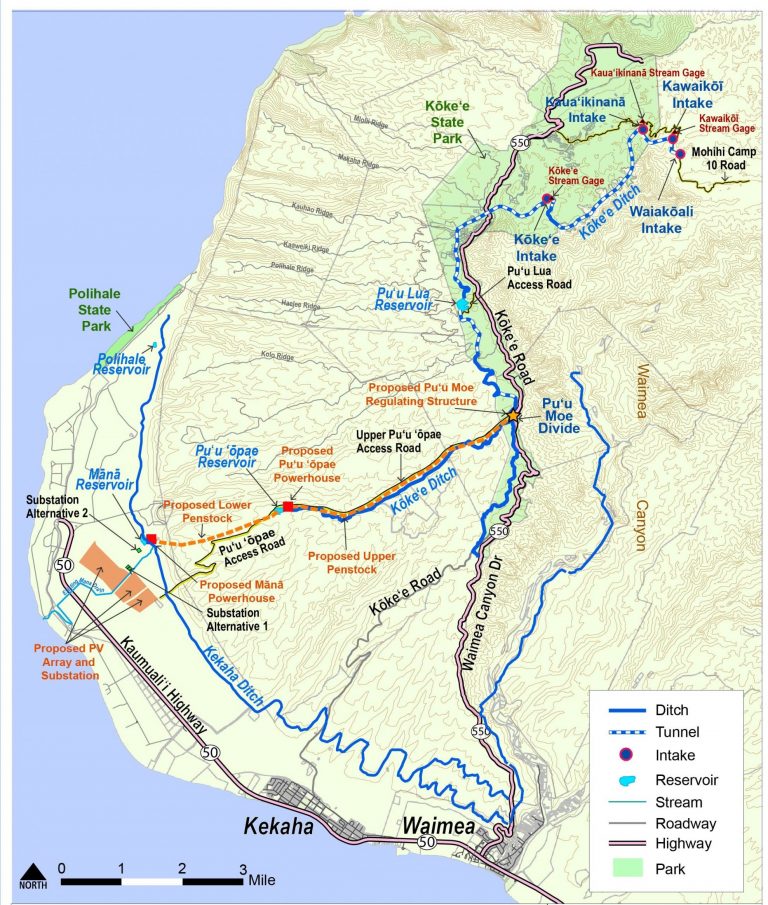

Conceived in 2012, the West Kauai Energy Project is an integrated pumped storage hydropower, solar, and battery project — the first of its kind in the world. Water diverted from the watershed using plantation-era ditch systems would move between preexisting reservoirs to produce power on cloudy days and at night, reducing the island’s reliance on fossil fuels when the sun doesn’t shine.

The project would give aging infrastructure new life as pillars of the island’s green energy future. Part of the project generates energy by moving water in a closed-loop system and is not in dispute. The subject of controversy is the portion of the system that would divert water outside of the watershed — a hotly contested plantation-era practice that for over a century dried up streams across the state in order to feed monocrop agriculture.

The Kekaha Sugar plantation used to extract water from the Waimea River to feed its lucrative export crop while undermining the viability of small family farms along the watershed. Even after the plantation’s closure in 2000, water continued to be piped and dumped into gulches, storm drains and ditches.

A watershed agreement forged in 2017 now sets an 11 million gallon daily limit for Waimea river water diversions, requiring that any diversion “must be justified with no more water taken than is needed for other beneficial uses.”

Kauai’s electric utility has proposed to supply over 6 million gallons of its water allotment to open up food production on dormant agricultural land where the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands plans to build 250 homestead farms and pastures as part of the envisioned Puu Opae Homestead Settlement. The energy project would also support these future farms by bringing in electrical access and road upgrades.

The rest of the diverted water would be made available for agriculture on the Mana Plains in fields managed by the Kekaha Agriculture Association and owned by the state Agribusiness Development Corp.

Farming would need to increase significantly in this region to make use of the water that the energy project would provide. But there is no comprehensive farm plan for the use of so much water on these lands. Critics worry that if there is insufficient agriculture to use the water at the end of the diversion, then a precious resource would be dumped and wasted.

A 3,600-page environmental assessment approved by the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources in late December found that the project would have “no significant impact” on one of Hawaii’s largest rivers. The agency’s approval precludes the project from performing a more rigorous environmental impact statement that community members say could help address their concerns.

West Kauai taro farmers and subsistence fishermen brought the project to a halt last month by filing a lawsuit against DLNR and its Board of Land and Natural Resources for failing to mandate the more tedious examination of the project’s environmental effects. The complaint says former DLNR Chair Suzanne Case improperly “rushed a rubberstamp approval” of the project’s environmental assessment three days before Christmas as one of her last acts as the department head.

DLNR spokesman Dan Dennison said the agency does not comment on pending litigation.

Image on left: Subsistence fisherman and fire captain Kawai Warren said he worries that a long history of water waste is on the verge of repeating itself. Brittany Lyte/Civil Beat Image on right: Kawai Warren and Wesley Yadao, a taro farmer, stand near the top of the plantation-era Kokee ditch system. Earthjustice

Represented by Earthjustice, the West Kauai farmers and fishermen who filed the lawsuit through the community groups Poai Wai Ola and Na Kiai Kai question how there could be no harm in diverting roughly 11 million gallons of water a day and then discharging some of that water onto the Mana Plain if there isn’t enough farming underway to make use of it.

The legal complaint argues that water dumped outside the watershed would collect sediment and pesticides left on the landscape from the plantation days on its way out to the ocean — a problem for the health of the nearshore marine environment.

“What we’re looking for is that commitment of one to one: For every gallon of water that they take from the watershed for hydroelectricity there needs to be one gallon of water made available for agriculture, ideally for taro farming,” said Marti Townsend, engagement specialist for Earthjustice, citing a term of a 2022 follow-up watershed agreement. “KIUC agreed to that, and our concern is that they are not going to be able to make good on that commitment.”

The addition of millions of gallons of daily water access could open up vast opportunities for the Kekaha Agriculture Association to expand farming on its thousands of acres, according to Mike Faye, who manages the farmers cooperative. Roughly 3,500 acres of active KAA farmland — mainly research seed corn but also vegetables and mango — utilize between 2 million and 3 million gallons of water a day, Faye said.

“We’re optimistically looking at this side of the island on Kauai with its great growing conditions — a lot of sun, for the most part good soil — and the missing part is this imported water,” said Faye, adding that KAA does not yet have a written farm plan for the water.

The utility has agreed to work with Poai Wai Ola to develop protocols to ensure that every drop of water diverted for hydroelectricity is, in fact, matched with water used for agriculture, according to KIUC spokeswoman Beth Amaro.

The farmers and fishermen say they aren’t against renewable energy. But they want full disclosure of the project’s environmental and cultural impacts.

“It’s not for us,” Yadao said of the fight for closer scrutiny of the project. “It’s for our great-grandchildren. For them, hopefully we can make the right decision.”

In the fight against climate change, Hawaii was the first state to commit to shift away from the fossil fuels heating the planet and create a purely renewable power supply by 2045. With roughly 60 percent of its grid now untethered from oil, Kauai’s electric utility is powered by the largest share of renewables in the state.

It’s also one of only a few utilities in the U.S. that’s capable of running on 100 percent renewable energy most of the day.

But when the sun disappears at night the utility’s battery storage kicks in, covering a portion of the evening peak when many families cook dinner, shower, and watch TV. Then the oil-fired generators rev up to meet the bulk of the island’s energy demand until morning.

The West Kauai Energy Project is poised to increase the utility’s renewable energy capacity to 80 percent, according to KIUC. It would achieve this in part by creating 12-hour energy storage capability that would stabilize the grid by bolstering electricity production from renewable sources when the sun’s not shining.

The project is estimated to save roughly 8 million gallons of oil annually, moving the utility closer to its goal of achieving 100 percent renewable energy production by 2033 — more than a decade before the state mandate.

Kauai’s energy portfolio currently includes 45 percent solar, 14 percent hydro, and 11 percent biomass. Finding new alternative energy sources or improving energy storage capacity through projects like the WKEP could be crucial to the effort to continue to phase out fossil fuels.

It’s not just about saving the planet, KIUC says.

There’s a financial incentive to embrace renewables. Hawaii’s electricity prices are higher than nearly anywhere else in the nation. For KIUC’s 34,000 members, the WKEP promises to reduce the cost of power by an estimated $157 million to $200 million.

The average ratepayer would save about $20 on their monthly electric bill, according to KIUC President and CEO David Bissell.

The advantage of transforming a mostly abandoned water diversion system into a renewable energy source is twofold: It saves time and money.

Constructing the WKEP would take up to three years at a cost of roughly $200 million, a tab that would be paid by the utility’s partner developer AES Corp, Bissell said.

“The ditches, water diversions and reservoirs are all relics of the plantation days and just need some rehabilitating,” Bissell said.

Eventually, KIUC will likely turn to biofuels to close the final 5 percent to 10 percent gap in its renewable energy portfolio, Bissell said. The WKEP stands to minimize the utility’s need for biofuels, helping to keep expenses in check. That’s because biofuels are an expensive renewable energy source that could impose a heavier hit on ratepayers.

“Finding ways to economically reach 100 percent is essential for our ratepayer members to be able to control their electric bill,” Bissell said. “This is great because it allows us to do that.”

The utility touts dozens more benefits, including temporary construction jobs and the use of the project’s rehabbed reservoirs for fire suppression and improved public trout fishing.

Kauai holds a prominent role in the production of taro, or kalo, a sacred crop tied to Hawaiian beliefs about creation.

Hanalei on the island’s north shore is the taro capital of Hawaii, home to farms that produce more than two-thirds of all the taro in the state.

Taro farming also has a storied heritage in Waimea, although many river-fed farms that once dotted the watershed were lost during the plantation era when water diversions left some agricultural regions dry.

Farming for taro across the islands has been declining year after year even as farmers say there is a growing demand.

The dozen farms that remain in Waimea are up against several threats, including aging farmers who find difficulty attracting a new generation to replace them and barriers to accessing land, water, and infrastructure.

Another concern: More frequent and severe drought. Farmers worry this expected consequence of climate change could reduce the volume of water in the Waimea watershed, jeopardizing a crop and a way of life that depends on the river.

Kawai Warren, a Kauai fire captain and subsistence fisherman who has lived on the west side for 40 years, said he worries that a long history of water waste in Waimea is on the verge of repeating itself.

“It’s not just the taro, but the life in the river that supports the nearshore fisheries that has been depleted by the plantation,” he said. “I thought it was time to let the river heal. But now they want to continue doing what the plantation did for 100 years.”

The project has been brought to a halt by the dispute, which has created frustration for residents who consider themselves protectors of the river as well as utility executives eager to achieve ambitious green energy goals. Until the lawsuit is resolved and the environmental assessment is cleared, KIUC can not move forward with securing permits and finalizing land agreements — precursors to starting construction.

For now, plans that constitute a giant leap forward for the island’s renewable energy future are stuck in limbo.

Civil Beat’s coverage of climate change is supported by the Environmental Funders Group of the Hawaii Community Foundation, Marisla Fund of the Hawaii Community Foundation, and the Frost Family Foundation.