It was less than a year ago, but everything seemed so different then. George W. Bush was still in the White House, but officials gathered at the annual international climate talks, held last December in Poznan, felt new hope in the chilly Polish air: President-elect Obama had, against many expectations, made it clear that combatting global warming was to be a priority for his incoming administration.

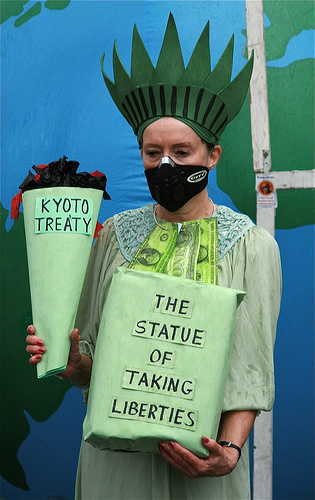

George W. Bush may no longer be president, but America is once again seen as the bad guy in the effort to negotiate a new climate change pact. Above, a gagged “Statue of Liberty” at a 2007 climate protest in Britain.jystewart via FlickrThe hope grew, if anything, in March when Obama’s new climate envoy, Todd Stern, traveled to Bonn and addressed the first of this year’s long series of climate negotiations. “We are very glad to be back, we want to make up for lost time, and we are seized with the urgency of the task before us,” he told the delegates, promising to engage “powerfully, fervently” in the talks, which were tasked with preparing for the vital climate negotiations in Copenhagen next month.

George W. Bush may no longer be president, but America is once again seen as the bad guy in the effort to negotiate a new climate change pact. Above, a gagged “Statue of Liberty” at a 2007 climate protest in Britain.jystewart via FlickrThe hope grew, if anything, in March when Obama’s new climate envoy, Todd Stern, traveled to Bonn and addressed the first of this year’s long series of climate negotiations. “We are very glad to be back, we want to make up for lost time, and we are seized with the urgency of the task before us,” he told the delegates, promising to engage “powerfully, fervently” in the talks, which were tasked with preparing for the vital climate negotiations in Copenhagen next month.

Things look very different today. In the eyes of most of the world, the United States has again emerged as the principal obstacle to a new international climate agreement, in stark contrast to India, China and other rapidly industrializing developing countries that, despite the widely held view of a year ago that they would be unlikely to cooperate on drafting a new pact, have actually moved further and faster to address the climate crisis.

As the final preparatory talks wound up in Barcelona at the end of last week without finalizing a negotiating text for Copenhagen, almost everyone had accepted that a new agreement would not be finalized in the Danish capital, thanks to the United States’ failure to deliver on last year’s hopeful signals.

Martin Kaiser, Greenpeace’s policy director, said U.S. intransigence was “threatening to kill the prospect of a legally binding Copenhagen treaty.” Oxfam added: “The U.S. shadow is looming large over the climate talks.”

Key delegates vented their frustration by breaking with protocol to point the finger towards Washington. “Clearly, the U.S. has been slowing things down,” said Artur Runge-Metzger, the European Union’s chief climate negotiator. Alicia Montalbo, chief negotiator for Spain (the next country to hold the rotating European Union presidency), echoed Kaiser’s sentiments more indirectly, saying: “There’s a certain level of frustration in seeing that not all countries share (the) vision.” More of the same came from Denmark’s climate minister, Connie Hedegaard: “We can’t imagine having an agreement without the United States, they have to be a part of it,” she told Agence France-Presse.

After visiting President Obama last week, Frederik Reinfeld, the Prime Minister of Sweden (and current EU president) said the slow progress of the U.S. Senate’s climate bill made adopting a legally binding agreement in Copenhagen impossible. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, addressing both houses of Congress on the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, devoted most of her speech to the need to address climate change, stressing: “We have no time to lose.”

Leaders across the globe occupying different spots on the political spectrum are also committed to achieving a climate deal soon. British Prime Minister Gordon Brown and French President Nicolas Sarkozy are on board, and they enjoy increasing support from such key developing country leaders as Hu Jintao of China, Manmohan Singh of India, Felipe Calderon of Mexico, and Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva of Brazil. Given the broad coalition for climate action, the Obama administration risks running into its greatest foreign policy crisis to date if it continues to stand in the way of a strong, new agreement.

In a sense, this is not Obama’s fault. He is the strongest advocate for action on climate change in the White House, just as his predecessor was its most fervent naysayer. He is personally as convinced of the importance of the issue as Merkel, Brown, Sarkozy, or any other leader — even if his closest political aides are not. And there is insufficient understanding in the rest of the world of the constraints imposed by the U.S. system of governance.

Never before has such a vital, international treaty depended so crucially on the 535 members of the U.S. Congress. Even previous environmental breakthroughs, such as the Montreal Protocol on the ozone layer or the Washington Convention on Endangered Species, were preceded by U.S. legislation. As such, the rest of the world is experiencing for the first time how its vital interests can be affected by American politics, as senators from coal or oil states object to legislation that would curb emissions from fossil fuels.

There is only limited understanding of Obama’s plight in the rest of the world, since in most countries the executive controls the legislature. It is understandable enough for a citizen of the Maldives, faced with the disappearance of his or her country due to rising sea levels, to become impatient that the “most powerful man on earth” is so constrained by his political system. But that is the fact of life, and the rest of the world needs to be careful not to make it more difficult to get the bill through Congress.

Mind you, the United States does not help when it attacks developing countries, as Stern did last week, for focusing “on citing chapter and verse of dubious interpretations…designed to prove that they don’t have any responsibility for action now, rather than thinking through pragmatic ways to find common ground to start solving the problem.” When those same countries have moved so much further on the climate issue over the last year than the Americans, this sort of rhetoric can only be seen as inflammatory.

Millions of words have been exchanged over the past year, but success at Copenhagen hangs on just one — trust. If there was trust, Obama could get the space he needs to win the political fight he faces at home. Unfortunately, it is a scarce and diminishing commodity as Copenhagen approaches. The president and his fellow leaders need to focus in the next few weeks on building it.