Tax credit transaction cost.This is part of a series of posts on distributed renewable energy that will be posted to Grist. It originally appeared on Energy Self-Reliant States, a resource of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s New Rules Project.

Tax credit transaction cost.This is part of a series of posts on distributed renewable energy that will be posted to Grist. It originally appeared on Energy Self-Reliant States, a resource of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s New Rules Project.

For two years, solar and wind energy producers seeking federal incentives have been able to take cash grants in lieu of tax credits. The stimulus act program helped keep the renewable energy industry afloat as the credit crunch and economic downturn dried up the market for reselling tax credits to banks and other investors with large tax bills.

The cash grant program is set to sunset at the end of this year, but solar and wind energy advocates are hoping it will be extended, for good reason:

In fact, the tax credits were always an awkward tool, some argue. Rhone Resch, the head of the Solar Energy Industries Association, said that many of the companies doing the installations were not making a profit either, so these tax credits were sold as “tax equity,” a secondary market, at a loss of 30 to 50 cents on the dollar to the seller. [Emphasis mine.]

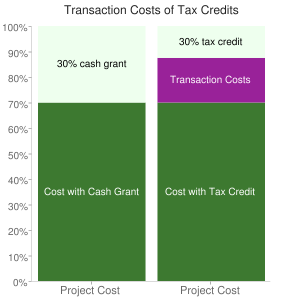

The tax credits were worth 30 percent of a project’s value, so the transaction costs of reselling the credits meant that renewable energy projects without sufficient internal tax liability were 13 to 21 percent more expensive than projects that could use the credits themselves.

This is dumb policy. Ratepayers pay a higher price for renewable energy because incentives filter through the tax code instead of the general fund.

But the cash grant vs. tax credit issue is just one symptom of a larger disease affecting American renewable energy policy. Transaction costs are increasing the cost of renewable energy in nearly every state with a renewable portfolio standard (RPS).

Under most state RPS policies, utilities put out requests for proposal to acquire renewable energy to meet the state mandates. These solicitations attract thousands of developers who all have to front their project development costs. But in California, for example, 90 percent of projects don’t make the utilities’ shortlist for the solicitation, stranding over $100 million in development costs.

Some of those projects may eventually get online, but most of that money is flushed because the U.S. prefers to let utilities act as gatekeepers to clean energy rather than open the market to any potential producer. It’s not the only way.

There’s a renewable energy policy that’s responsible for 75 percent of the world’s solar and half its wind power. It has the lowest transaction costs because there’s no fiddling with the tax code and no parasitic costs from auctions or solicitations. Instead, utilities are required to interconnect and take the power from any developed renewable energy project, and to provide a price sufficient to provide a reasonable return on investment (just like the utilities enjoy in rate regulated states).

The policy is funded entirely through the electricity system, so renewable energy doesn’t have to compete with other budget priorities.

It’s called a feed-in tariff.

The U.S. can extend the cash grant program, but it merely treats a symptom of the disease. A better policy awaits.