Climatopolis by Matthew Kahn has a deeply flawed main thesis, captured in its subtitle, “How Our Cities Will Thrive in the Hotter Future.” On page after page you will find assertions that are dubious, unsubstantiated, or just plain wrong. Also, the book does not appear to have been well-edited. Indeed, it contains at least one (repeated) glaring quantitative error that is so egregious it is very puzzling how it could have persisted to the final version.

Climatopolis by Matthew Kahn has a deeply flawed main thesis, captured in its subtitle, “How Our Cities Will Thrive in the Hotter Future.” On page after page you will find assertions that are dubious, unsubstantiated, or just plain wrong. Also, the book does not appear to have been well-edited. Indeed, it contains at least one (repeated) glaring quantitative error that is so egregious it is very puzzling how it could have persisted to the final version.

But most importantly, the author just doesn’t know what he’s talking about because he hasn’t done his homework. It bugs me that so many economists — in a discipline notorious for leaping all over non-economists who write on economic matters without doing their homework — write so much about climate change without reading the extensive climate science literature or talking to leading climate scientists.

Readers know I already debunked the book’s central thesis. So why am I doing another piece?

Well, the author sent me an email titled “Brad Delong’s question for you” with a link to a post by Berkeley economist Brad DeLong who apparently thinks that you can’t debunk a key thesis of a book unless you read every single word of it. He’s wrong about that — DeLong and I both did just fine eviscerating the nonsensical global-cooling/geoengineering chapter in Superfreakonomics. In any case, a very large fraction of Climatopolis is online and I read that, searched other parts, read writings that Kahn pointed me to, and saw how the notes were almost completely devoid of actual references to climate science.

I do have respect for DeLong as an economist, but he simply asserts the book is “very good” without defending that assertion at all or responding to my extensive debunking of it. Fundamentally, Climatopolis will appeal mainly to those who haven’t seriously read the climate science literature or talked to leading climate scientists. That would appear to include DeLong, who, while he has a better understanding of the climate than many economists, still managed to write this sentence earlier this year: “Unless the North Atlantic Conveyor shuts down and Europe returns to the climate of the Younger Dryas Era, global warming is not a huge deal for the North Atlantic economies for a century.” Not so — see, for instance, “U.S. southwest could see a 60-year drought like that of 12th century — only hotter — this century” and links to the literature below.

I suppose I’ll have to do a separate post on this, but global warming will almost certainly become the hugest imaginable deal for the North Atlantic economies with a quarter century. Indeed, the way it’s looking now, by the 2030s, if not sooner, all of the major economies of the world will be focusing all of their economic policy desperately on adaptation and mitigation. But I digress.

Author unfamiliar with relevant literature

Climatopolis is just not a good book. It’s not even a so-so book. That’s clearer now that I’ve read the whole thing. To start, the author just doesn’t know what he’s talking about. You don’t have to take my word for it. You can read this detailed review, “A Fantasy Future,” at the American Scientist by David Satterthwaite, a leading expert on the impact of climate change on cities (he coedited the book Adapting Cities to Climate Change), who concludes:

Unfortunately, it fails on the most important criterion: a good knowledge of the topic under discussion. There is little evidence that author Matthew E. Kahn, an economist, has familiarized himself with the literature on climate change and cities. For instance, there are only a few references to papers from the leading climate and urban journals, and no mention is made of any of the assessments of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Yet in the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report, which was published in 2007, one finds a version of Kahn’s main thesis that is more accurate and more nuanced than the one set forth in the book. The report indicates that many cities have a capacity to adapt to climate change, just as in the past they have adapted to environmental conditions and to frequent changes in resource prices and availabilities. The book goes further. Its subtitle, How Our Cities Will Thrive in the Hotter Future, suggests that cities will not merely adapt, but flourish; however, a subtitle that better reflects the content would be How Some Cities in a Few Prosperous, Large Nations May Benefit from Global Warming in the Next Few Decades.

In 14 pages of notes, there are two or three actual references to peer-reviewed climate science papers, one of which is, “Impact of a Century of Climate Change on Small-Mammal Communities in Yosemite National Park, USA,” which isn’t exactly on anyone’s list of top 500 papers you should read if you want to understand what will happen to cities and humanity because of human-caused global warming. The page of “suggested further reading” contained not a single peer-reviewed climate science paper.

For the record, if economists want to engage in this debate, if they want to make sweeping statements about what we face, if they want to insist that people have to read every single word they write, then are about three dozen articles they should start with:

- Royal Society special issue details ‘hellish vision’ of 7 degrees F world — which we may face in the 2060s!

- A stunning year in climate science reveals that human civilization is on the precipice

And before Kahn complains that most of those papers were published while his book was being printed, here’s a bunch of earlier ones that spell out what we face:

Economists who fail to read the literature will likely end up putting stuff out like Climatopolis.

The big, sloppy blunder plus many smaller ones

Ironically, while I have been urged to read this book closely to review it fully, apparently I have ended up reading this book more closely than any of t

he editors or perhaps the author himself. On pages 211-212, Kahn writes:

A carbon permit price of $50 per ton of carbon dioxide is predicted to raise the price of gasoline by 26 percent …

Consider the trucking industry. Its average fleet fuel economy is roughly 6.5 miles per gallon — so traveling 1,000 miles requires 154 gallons of gasoline. At $3 a gallon, this costs $462. If carbon dioxide emissions are priced at $25 per ton, then gas prices would rise by 50 cents per gallon. If gasoline costs three dollars per gallon (pre-carbon tax), the price of gas could increase by as much as 16 percent.

No.

Like any economist, Kahn is quick to use numbers and do calculations. But he needs to double check the ones he publishes.

Let’s set aside the confusing construction “A carbon permit price of $50 per ton of carbon dioxide” which would be considerably clearer without the first “carbon.”

Let’s (temporarily) set aside the fact that trucks use diesel fuel, not gasoline.

I knew the number was wrong from my days at the Department of Energy working on the Five Lab study, which notes the key fact to remember about a carbon price: “$50 per ton of carbon corresponds to 12.5 cents per gallon of gasoline.” Translating to CO2 and tons tells us that if CO2 is priced at $25/ton, gas prices would rise 25 cents per gallon — not 50 cents.

That is a factor of two error. Could happen to anyone, right?

I would call that only a medium-sized error, except for one thing — the author references a footnote which does the calculation from first principles:

A gallon of gasoline creates roughly 22 pounds of carbon dioxide. This equals (22/2000) tons; valued at $25 per ton this creates 25 x 22/2000 dollars’ worth of social cost.

Uhh, Prof. Kahn, “25 x 22/2000 dollars” is 27.5 cents — not 50.

D’oh! Kahn’s footnote gives the right answer, but the text that cites the footnote gives the wrong answer! And not just once, but twice. On page 213, Kahn writes, “It is possible that by the middle of the twenty-first century carbon taxes could be $100 per ton. If carbon prices rise this high, this would be the equivalent of placing a $2-per-gallon tax on gasoline.” No. Again, $100 a ton price for CO2 is closer to $1 a gallon tax on gasoline.

But wait, there’s more sloppiness. In Kahn’s calculation above he writes, “A gallon of gasoline creates roughly 22 pounds of carbon dioxide.” In fact, as the EPA notes here, “CO2 emissions from a gallon of gasoline … = 19.4 pounds/gallon” whereas “CO2 emissions from a gallon of diesel … = 22.2 pounds/gallon.” (The U.S. Energy Information Administration uses 19.5 and 22.4.)

Kahn has done his calculation in the footnote with the correct fuel for trucks, diesel, but he insists on calling the fuel “gasoline” in both the text and the footnote. Double D’oh!

This kind of easily-checked sloppiness runs throughout the book. If I wanted to waste another hour I could give you a half a dozen examples. Here’s one. Kahn devotes a page and a half to a discussion he titles, “The Birth of a Hydrogen Hummer.” Seriously. It includes these lines:

If smart engineers could design a hydrogen Hummer, Arnold Schwarzenegger could have the best of both worlds, enjoying his tanks while releasing zero carbon emissions. Carbon pricing in a social media campaign celebrating the virtuousness of owning such a vehicle would stimulate demand for it.

Uhh, Prof. Kahn, back in February, the media reported that the deal GM had to sell Hummer failed, at which time this section should’ve been pulled from the book entirely. On April 7, 2010, “General Motors officially said it is shutting down the Hummer SUV brand.”

Also, more than 90 percent of U.S. hydrogen is made from natural gas in a process that releases considerable carbon dioxide. Carbon-free hydrogen is certainly possible to make, but quite expensive. Kahn has no discussion whatsoever of this issue here.

Back in March 2009 (if not earlier), it was clear that California simply didn’t have the money needed to put together even a minimal hydrogen infrastructure. Again, Kahn has no discussion of the well-known hydrogen fueling infrastructure problem.

Basically, Kahn just opines on stuff that he doesn’t know very much about in this book, not just climate science but also energy. On page 201, he writes:

Climate change will increase the demand for electricity, and climate change mitigation effort (such as a carbon tax) will mean that we are increasingly generating electricity using unreliable, renewable power generation (such as wind turbines). When the wind does not blow or the sun does not shine, these “green” renewables produce little power. Serious spikes in electricity prices are likely to occur.

Seriously, this is about the depth with which he approaches most subjects. He appears not to heard very much about energy storage — he might start here: “The Holy Grail of clean energy economy is in sight: Affordable storage for wind and solar.” He appears not to have heard about concentrated solar thermal power at all, since it can rather trivially generate power when the sun doesn’t shine (see “Concentrated solar thermal power Solar Baseload — a core climate solution“). While he can imagine and opine on a carbon-free hydrogen Hummer, a vehicle that has no future, he is apparently unaware that many believe it quite plausible that electric cars and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles could help provide some of the storage for intermittent renewables. For the record, if we put in place a steadily rising price on carbon and other intelligent clean energy problems, there is no reason to think we will see more electricity price spikes than we have in the past, and we’d probably see fewer.

Book’s central thesis is wrong

For completeness’s sake, let me revise and extend my earlier debunking.

A key “thesis” of this book is that people will just move to northern cities and be fine. And so you will learn on page 7 … wait for it … “Moscow is unlikely to suffer from extreme heat waves.” Talk about your badly timed books.

On page 75, he says, “Moscow scores high on my list.” He just seems to miss the point that climate change means extreme weather events on top of a moving average. But then he has done precious little actual research into the science.

You can read an interview with Kahn on Grist, “Don’t like the climate? Move to Fargo, says author of Climatopolis.” I actually thought this was one of Grist’s jokey headlines, but you can search the book for “Fargo.” On page 51, y

ou’ll learn:

The current residents of North Dakota’s cities, such as Fargo, might not be too happy about having loud-mouthed New Yorkers moves [sic] in by the millions …

As Brad Johnson noted last year:

North Dakota’s climate [PDF] is beginning to spiral out of control. In the last 20 years, Red River floods expected to occur at Fargo only once every ten years have happened every two to three years. 2009’s unprecedented flooding made it the third year in a row with at least a “ten-year flood.”

In fact, 2009 was the eighth “ten-year flood” of Fargo since 1989. They just don’t make ten-year floods like they used to.

So I’m skeptical that millions of New Yorkers will be rushing to the likes of Fargo, with its metropolitan population of 200,000.

On page 33, Kahn calls Salt Lake City, Utah a “climate safe city.” The southwestern city is Kahn’s #1 choice as the most “climate resilient” U.S. city. Not!

“Salt Lake City cannot flood,” he writes on page 7. Apparently it never occurred to Kahn to Google “Salt Lake City flood” or he would have seen this:

State Street/800 South Salt Lake City — City Creek Flood — 1983

State Street/800 South Salt Lake City — City Creek Flood — 1983

D’oh!

But I’ll grant that, in general, the big climate problem facing Salt Lake City isn’t too much water.

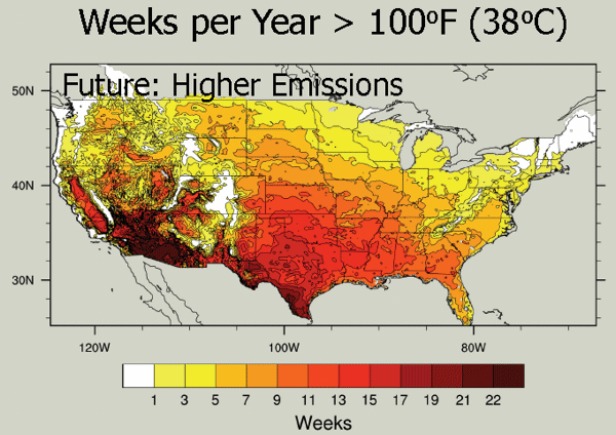

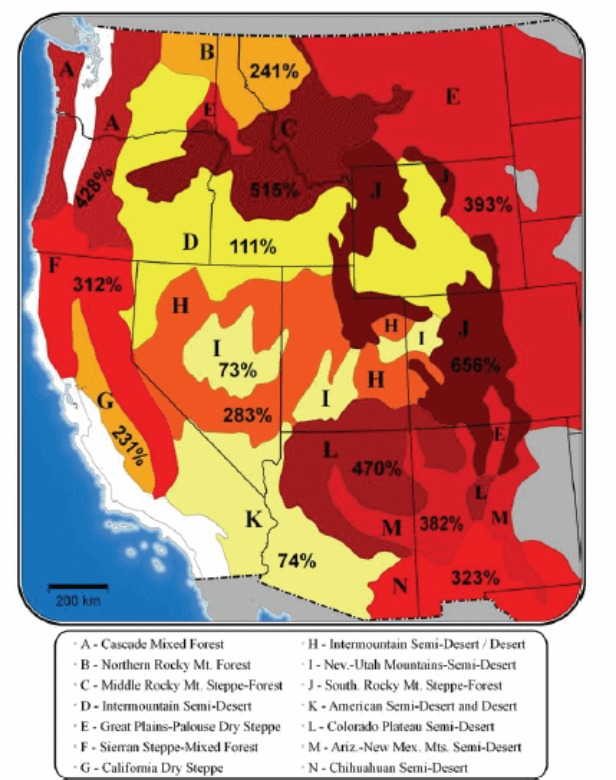

In a terrific March presentation, climate scientist Katherine Hayhoe has a figure of what staying on the business-as-usual emissions path (A1F1 or 1000 parts per million) would mean (derived from the NOAA-led report):

Hey, looks to me like the greater Salt Lake City would only be above 100 degrees F for most of the summer. Let’s move there!

Hey, looks to me like the greater Salt Lake City would only be above 100 degrees F for most of the summer. Let’s move there!

I’m sure the rest of the year would be climate safe … although in fairness to would-be eco-immigrants, the travel brochure should probably include this chart from the National Academy of Sciences 2010 report, Climate Stabilization Targets: Emissions, Concentrations, and Impacts over Decades to Millennia:

Yes, that is just from a 1 degrees C (1.8 degrees F) warming (by mid-century). We’re facing a lot more of that by century’s end if we listen to the likes of Kahn.

Sure, there might be a few hundred percent increase in median annual burn area around Salt Lake City, but surely the burn season won’t last more than six months out of the year, eight tops, so I’m sure Salt Lake City will be climate safe a few months of the year.

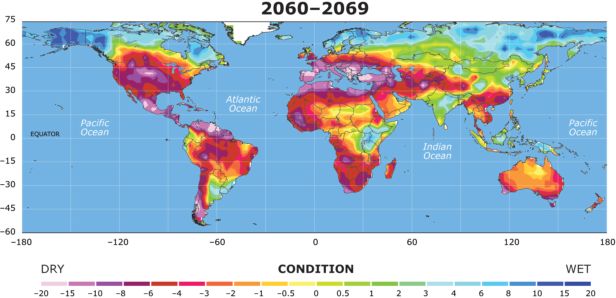

Back in 2007, Science ($ubreq) published research that “predicted a permanent drought by 2050 throughout the Southwest” — levels of aridity comparable to the 1930s Dust Bowl would stretch from Kansas to California. This year, the National Center for Atmospheric Research warned that by mid-century, the Southwest faces a drought index worse than that of the 1930s dust bowl.

“The maps use a common measure, the Palmer Drought Severity Index, which assigns positive numbers when conditions are unusually wet for a particular region, and negative numbers when conditions are unusually dry. A reading of -4 or below is considered extreme drought …”

See also two more studies discussed here: “U.S. southwest could see a 60-year drought like that of 12th century — only hotter — this century.”

So, no, Salt Lake City is not one of the U.S. cities with a very bright climatic future. Quite the reverse.

On page 70, he writes, “people sent to Houston will be safe from scary climate change risks such as flooding”! Well, yes, it rises to about 43 to 50 feet above sea level, but parts of the city are quite near the coast and low-lying. And has Kahn never heard of hurricanes? I dare say that by the second half of the century, the citizens of Houston, especially the eastern suburbs, will be concerned about flooding pretty much every summer.

I apologize for not warning you to put your head in a vise for this review.

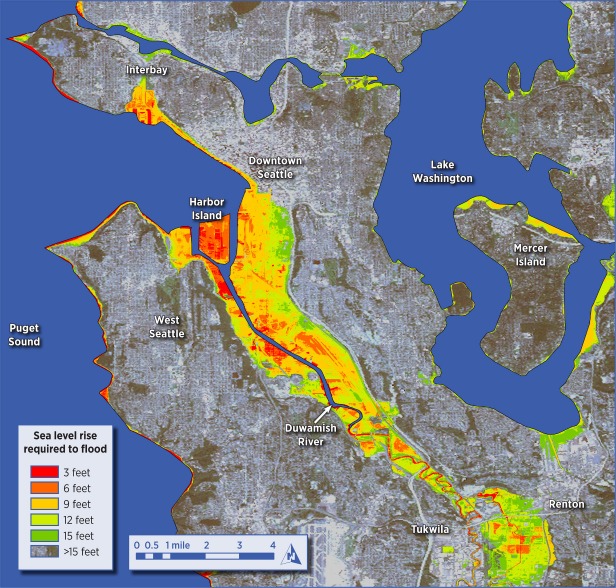

Kahn tells Grist of another “winning” city: “I think that Seattle will compete much better in the hotter future.” Really?

Sure, Seattle is a great city to live in now, and it wouldn’t be utterly devastated by the first three feet of sea level rise. But assuming we listen to Pollyannas like Kahn and don’t take strong action to sharply reduce emissions, then I hardly think a lot of people will be rushing to move into Seattle in the second half of this century, when everybody knows what is coming, what can’t be stopped, and what they risk under the worst-case scenario:

- Sea levels may rise three times faster than IPCC estimated, could hit six feet by 2100

- West Antarctic ice sheet collapse even more catastrophic for U.S. coasts

- New study of Greenland under “more realistic forcings” concludes “collapse of the ice-sheet was found to occur between 400 and 560 ppm” of CO2

As you can tell, Kahn’s book is almost devoid of actual science. The notes are stuffed with citations to newspaper pieces and articles by economists, but,

as I’ve pointed out, only a few references to actual, peer-reviewed climate science studies.

Given that over a year ago, the U.S. Global Change Research Program published an exhaustive multi-agency analysis of Global Climate Change Impacts in United States — see “Our hellish future: Definitive NOAA-led report on U.S. climate impacts warns of scorching nine to 11 degrees F warming over most of inland U.S. by 2090 with Kansas above 90 degrees F some 120 days a year, and that isn’t the worst case, it’s business as usual!“) — you’d think that the book would contain extensive references to it, but it doesn’t.

I know what you’re thinking. Kahn must be assuming a lot of mitigation for cities like Salt Lake City and Moscow to thrive. You think wrong!

David Satterthwaite makes a good point about two of the book’s “major flaws” in his review:

The first is that Kahn does not recognize that reduction of greenhouse gas emissions needs to be among our highest priorities right now. As the IPCC assessments make clear, any delay in getting an effective global agreement to reduce emissions makes it all the more unlikely that we will be able to avoid dangerous climate change. The book focuses too much on the short term — the likely impacts over the next few decades — and ignores times further in the future, when the effects of climate change may be grave if we take no action now. Kahn, although he acknowledges that large-scale reductions in carbon emissions would be required to lower the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, does not appear to understand that well-off households will need to do a lot more than buy an efficient washing machine and air conditioner and the latest Prius.

The second problem is that Kahn does not understand the scale and nature of the risk facing most cities (and national economies) in low- and middle-income countries. The book purports to be about cities worldwide; there are passing references to places such as London, Paris, Berlin and Masdar (in Abu Dhabi), and a chapter is devoted to cities in China. But the chief focus is on cities in the United States: A whole chapter is devoted to New York City, and large portions of another chapter deal with Los Angeles; Miami, New Orleans, Detroit, Salt Lake City and others are also discussed. Kahn assumes that low- and middle-income countries will have problems similar to those of wealthy countries, and that cities in the poorest nations will have the same adaptive capacity as prosperous Chinese cities. He admires China, and although he has no good word for governments in wealthy democracies, he thinks that China will have an adaptation edge because of its governance, and because of its skilled population. He vastly overestimates the capacity of cities in low-income and many middle-income nations to adapt. He also greatly overestimates the likelihood that insurance will support needed adaptations; only a very small proportion of urban residents in low-income nations have disaster insurance. After all, why should insurance companies offer policies to people with limited ability to pay, whose levels of risk are already high and increasing?

The book is focused on rich countries. Bangladesh — you’re on your own, you don’t even merit an entry in the book’s index!

And Kahn is not a mitigation guy. Indeed, as we’ve seen, he knows about as much about energy as he does about climate science. He writes on page 5:

I see no credible signs global emissions will decline in the near or medium future. Although the carbon mitigation agenda — the plan to reduce our emissions — is a worthy goal, we are unlikely to invent a magical new clean technology that allows us to live well without producing greenhouse gases.

Where is Harry Potter when you need him to solve the climate crisis? If only there were some technologies in existence today!

No, Kahn’s “vision” is “that we will save ourselves by adapting to our ever-changing circumstances.”

In short, good luck, billions of poor people post-2040. No need to push hard for magical mitigation. Just buck up and walk it off … all the way to Moscow and Salt Lake City! I’m sure you will be welcomed with open arms. Or at least with arms.