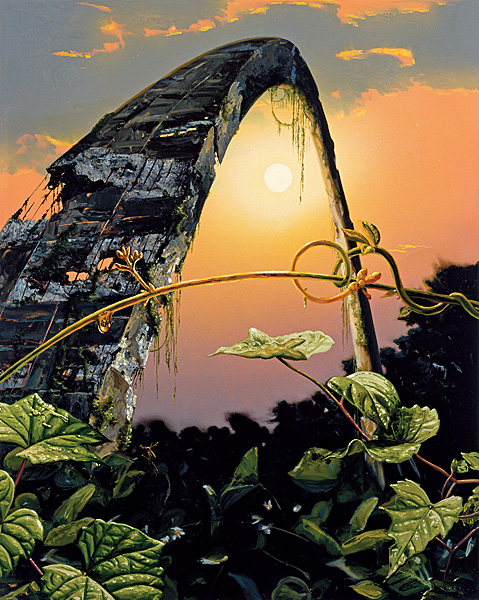

“(Untitled) St. Louis, 2005”Image: Alexis RockmanWhat role should art play in efforts to fight climate change and inspire people to address it? As the climate movement struggles to regain its bearings and look for new tools to reinvigorate itself after the failures of the 111th Congress, Copenhagen and Cancun, this question may be as relevant as any other that movement leaders and activists are asking themselves, especially given the unique role of art as a political and cultural magnifying glass.

“(Untitled) St. Louis, 2005”Image: Alexis RockmanWhat role should art play in efforts to fight climate change and inspire people to address it? As the climate movement struggles to regain its bearings and look for new tools to reinvigorate itself after the failures of the 111th Congress, Copenhagen and Cancun, this question may be as relevant as any other that movement leaders and activists are asking themselves, especially given the unique role of art as a political and cultural magnifying glass.

It’s also a question one can’t help but ask after visiting painter Alexis Rockman’s exhibit, “A Fable for Tomorrow”, now showing at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through May 8th, 2011. Many of the works in the exhibit seem to inhabit a zone somewhere between art and activism. They possess an energy that seems to reach out and pull you into the twisted and ruined worlds Rockman has documented and envisioned, before throwing you back into your life with a heightened urge to do something to stop the trajectory of destruction.

Indeed, much of Rockman’s oeuvre reads like a visual indictment against the vast catalog of offenses that humanity has committed against the natural world that we depend upon for survival. Among the particular transgressions Rockman has highlighted with his brush we find genetic engineering, factory farming, and of course, the mother of them all: climate change — a subject which Rockman addresses with particularly unnerving and humbling clairvoyance in his American Icons series. The Icons paintings depict symbols of American power and prestige ultimately undone by an abuse of the very powers that willed them into reality, such as a crumbling Gateway Arch, or the more fanciful, (Untitled) Mt. Rushmore with floodwaters lapping at the chins of the granite presidents. And our incoming freshman class of congressional climate deniers might want to go and check out a small canvass on which the U.S. Capitol Building emerges from an overgrown landscape, draped in a thick blanket of vegetation like the ruins of a Mayan temple.

Reflecting on the importance of Rockman’s work to our awareness of climate change, legendary climate organizer, author and activist Bill McKibben wrote in Orion Magazine that the paintings “complement the new satellite photos showing, for instance, that the North Pole has 20 percent less ice than it did when Apollo sent back those loving shots of our island Earth and we all pretended that we cared.” Yet for all their poltical potentcy, Rockman has a tendency to downplay his paintings’ real world political resonance. While readily admitting that “just about everything we do is political,” when asked if he views his work as a form of activism his response was self deprecating: “Only in the most marginalized sort of way.” As an example, Rockman pointed to his epic 2004 painting, Manifest Destiny — now on display at the Smithsonian exhibit — which depicts the flooded, decaying ruins of a climate-change-ravaged New York City.

“That painting,” he says, “came from desperation that people refused to see the reality of climate change.” With very little public discussion of the crisis, he felt compelled to make a statement about the consequences of our complacency, and he “felt a tremendous relief when Al Gore came in and made An Inconvenient Truth.” By bringing the climate issue to a mass moviegoing audience, Rockman felt that the Academy Award winning documentary, “let him off the hook,” suggesting that political inspiration is a job best left to politicians. He also suggested that film in general might be a better artistic medium for inspiring public action.

Rockman’s deference to film can be seen in his tendency to depict iconic locations as the victims of environmental collapse — a formula that comes right out of Hollywood disaster movies where major landmarks are always the first things to go. And no doubt he’s right that film does have a capacity to reach a larger audience; but that fact shouldn’t be used to discount the unique power of more “rarified” fine art like Rockman’s canvasses. Indeed, seeing those post-apocalyptic images set in frames and hung on the walls of a Smithsonian gallery seemed to imbue them with more gravity and reality than even the very best computer-generated sound and fury Hollywood could conjure.

Some visitors to the exhibit, such as Alan Braddock, agree. An assistant professor of art history at the Temple University, Tyler School of Art, Braddock explained how he has seen firsthand the power that Rockman’s works have to connect his students to the political and cultural issues that they confront. Addressing Rockman from the audience during the question and answer session at an exhibit lecture last week, Braddock insisted on the artist’s role as a force in the realm of political activism, telling him “I think you are the person that can bring [these issues] to a larger audience.”

Following the lecture, Braddock compared the political relevance of Rockman’s paintings to those of Diego Rivera, whose Rockefeller Center mural Man at the Crossroads stirred controversy that provoked its destruction in 1934. “Artists like Rivera were taking a risk and playing with fire, by addressing politically charged subjects,” Braddock said. “Through his work Rockman is playing with another kind of fire, and challenging the status quo. I think it will be interesting to see how his reputation as an important voice grows.”

Following his debut at a forum as prestigious as the Smithsonian, it’s likely that Rockman’s reputation will in fact only continue to grow. And it’s a good thing too. Though a somewhat reluctant player in the political arena, there is little doubt that he remains one of the world’s most inspiring and potentially influential creative voices regarding the environmental crises we are facing.

As those of us daily laboring within the trenches of climate activism know all too well, our movement needs all of the sources of inspiration and creative thinking that we can get. So as we look for new ways to motivate activists into action, we could do a lot worse than encouraging people to visit “A Fable for Tomorrow,” and we can only hope that there will be more of the same to come from Alexis Rockman.