As the border organizer for Sierra Club’s Environmental Justice program, I bounce back and forth across the U.S.-Mexico border supporting grassroots environmental activists. More than the food, language, or currency, the biggest difference from one side to the other is what issues are considered “environmental.” Perhaps nowhere else on earth is there such a long border between such a rich country and such a struggling one, and this disparity seems to carry over to which issues take priority.

Reynosa residents head to a community water source.

Photos: Oliver Bernstein.

For example, Laguna La Escondida in Reynosa, Mexico, a water source for the surrounding community whose name means Hidden Lagoon, is also an important migratory bird stopover point. Reynosa citizens concerned about their environment are working to clean up the lagoon to protect their families’ health from the waste dumped into its waters. Neighboring Texas citizens concerned about their environment are working to clean up the lagoon to prevent habitat destruction for hundreds of migratory birds. This binational effort is a terrific start, but it avoids confronting the issue of poverty. For all their goodwill and concern, the Texans’ narrow focus on bird habitat prevents many of them from seeing the bigger problem — human habitat.

Since the enactment of NAFTA in 1994, rapid industrialization along the border has led to some of the fastest population growth in either country. Almost 12 million people now live in Mexico and the United States along the nearly 2,000-mile border, and by 2020 that number could reach 20 million. This is not “smart growth,” but instead a ferocious growth to support the movement of consumer goods.

NAFTA was supposed to bring economic prosperity to Mexico, but the poverty and human suffering along the border tell a different story. Mexico’s more than 3,000 border maquiladoras — the mostly foreign-owned manufacturing and assembly plants — send about 90 percent of their products to the United States. The Spanish word “maquilar” means “to assemble,” but it is also slang for “to do someone else’s work for them.” This is what’s really going on; the maquiladora sector produced more than $100 billion in goods last year, but the typical maquiladora worker earns between $1 and $3 per hour, including benefits and bonuses. Special tariff-free zones along the border mean that many maquiladoras pay low taxes, limiting the funds that could improve quality of life.

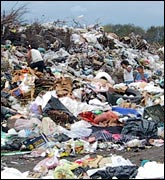

Those who don’t work in the maquiladoras live in their shadows. The industrial growth has drawn more people and development to the region, putting additional pressure on communities and the environment. Towns that until recently were small agricultural settlements now produce toxic chemicals for a worldwide market. Informal, donkey-drawn garbage carts cannot keep up with the waste stream from booming border cities. The natural environment suffers, indeed, but the most immediate suffering is human.

Pepenadores, or scavengers, sift through a landfill in Matamoros.

I recently visited a community near Matamoros, at the eastern end of the border, where the streets and canals were filled with trash. Rather than a classic litter campaign, the local activists explained that their biggest concern was the roads. If the local authorities don’t pave the road, they told me, the garbage trucks cannot get in and pick up the waste. Even burning the waste would be preferable to having to live with it in their homes, they say. The activists lament the polluted canals and the litter, but their focus is on the people. Without regular pickups, families live with trash piling up in their houses, and their children get sick.

South of Tijuana, on the western end of the border, a small environmental group advocates for more drains and sewers. Heavy seasonal rains flood the valleys and bring sewage and trash tumbling down to the beaches. While a goal of the local campaign may be to have cleaner beaches and unpolluted water, the way to reach that goal is by talking about quality-of-life issues like proper drainage from homes, regular trash pickup in outlying areas, and safe drinking water — something that 12 percent of border residents do not have. In the United States, these issues are all too often considered a given, lumped into the category of “basic services.” But even in the U.S. there are people who suffer as we ignore their poverty, having decided that it is not an environmental issue.

People are an important part of an ecosystem. If they are poor and unhealthy, then the ecosystem is poor and unhealthy. Many Mexican activists know this too well, but the closest thing the mainstream environmental movement in the United States has to this integrated people-and-poverty approach is the often neglected environmental-justice movement. The EJ movement works for justice for people of color and low-income communities that have been targeted by polluters. The EJ movement is our salvation — but we must stop viewing it as extracurricular to the business of conservation.

It’s time to support the right to a clean and healthful environment for all people. This means that residents in the border region should not suffer disproportionately from environmental health problems because of the color of their skin, the level of their income, or the side of the international line on which they live. It also means that environmental activists should not look past human poverty to save an endearing species, but must look instead at the big picture.

The cries of intense poverty and injustice across the world are getting louder. It is time for the environmental movement to listen, and to act.