By Janet Larsen

Half the world’s pigs—more than 470 million of them—live in China, but even that may not be enough to satisfy the growing Chinese appetite for meat. While meat consumption in the United States has fallen more than 5 percent since peaking in 2007, Chinese meat consumption has leapt 18 percent, from 64 million to 78 million (metric) tons—twice as much as in the United States. Pork is by far China’s favorite protein, which helps to explain the late-May announced acquisition of U.S. meat giant Smithfield Foods Inc., the world’s leading pork producer, by the Chinese company Shuanghui International, owner of China’s largest meat processor. China already buys more than 60 percent of the world’s soybean exports to feed to its own livestock and has been a net importer of pork for the last five years. Now the move for Chinese companies is to purchase both foreign agricultural land and food-producing companies outright.

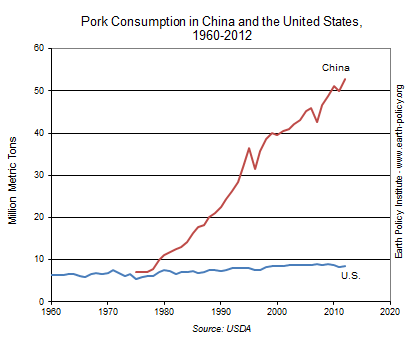

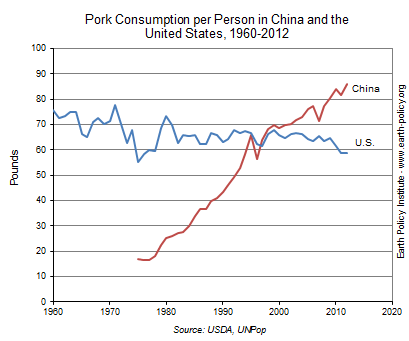

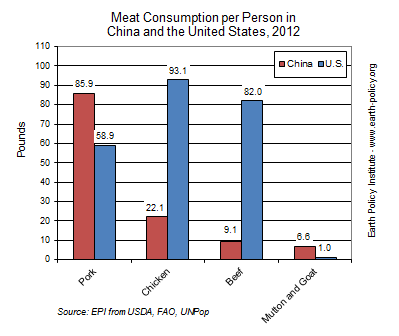

People in China ate 53 million tons of pork in 2012—six times as much as in the United States. On a per person basis, consumption in China first eclipsed that in the United States in 1997, and it has never looked back. Now the average Chinese eats 86 pounds (39 kilograms) of pig meat each year, compared with 59 pounds in the United States. As demand rises, pork is starting to shift from household- or farm-scale production into larger factory-like operations. Overcrowding in these facilities has been blamed for pollution and the spread of disease, as well as for the recent dumping of thousands of dead pigs into a river flowing into Shanghai.

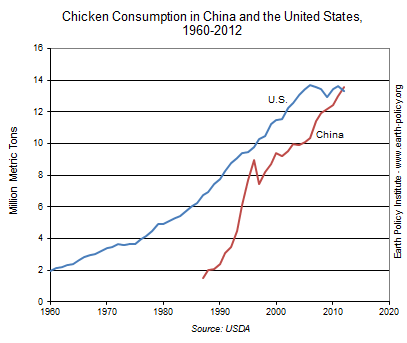

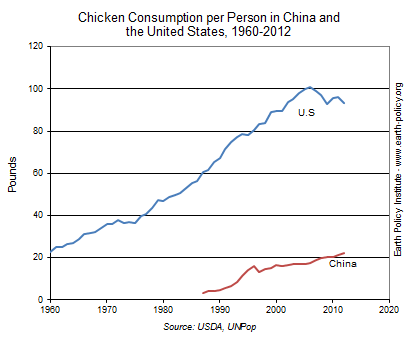

Chinese chicken production and processing have also consolidated, as sadly seen in the recent fire at a large poultry plant in northeastern China that reportedly killed at least 120 people. China’s chicken intake just recently caught up with that in the United States, with 13 million tons eaten in each country. It took China just 25 years to make the consumption leap achieved by the United States over a half-century.

Chicken is America’s meat of choice, and U.S. individual diets are four times heavier with poultry than Chinese diets are. However, as fast-food restaurants in China multiply, chicken consumption is rising. If the Chinese ate as much chicken per person as Americans do, their flocks would need to quadruple—as would the grain and soybeans used in the feed rations.

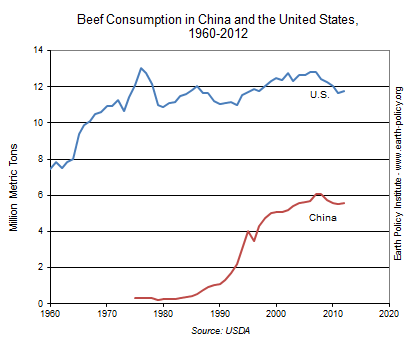

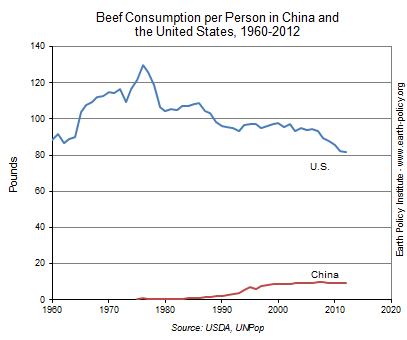

As for beef, grazing land limitations and higher costs have made this meat far less popular in China than in the United States, with 5.6 million tons consumed in 2012, or 9 pounds per person. The average American, in stark contrast, ate 82 pounds of beef that year. Total beef consumption in both countries appears to have peaked.

The Chinese eat nearly as much mutton and goat (close to 7 pounds per person annually) as they do beef, while those meats barely register in U.S. diets. New steakhouses are trying to lure affluent Chinese toward red meat, but they are unlikely to reach the masses. If the Chinese ate as much beef as Americans do today, they would need 50 million tons of it, 90 percent of current world consumption.

With the average income in China poised to reach U.S. levels as early as 2035, heavier beef consumption theoretically could become economically feasible. Ecologically, though, it may never be possible. Grasslands are unable to sustain herds much larger than the existing ones, as evidenced by the vast dust bowl forming in northern China, largely from overgrazing by sheep and goats. Thus, getting more beef would mean intensive use of feedlots. But cattle take more grain and soybean meal per pound than all other livestock and poultry. In recent years China has imported some grain, though imports still make up a small share of its total supply. China’s soy production, however, has barely budged since 1995, while soy use (mostly for feed rations) has shot up fivefold. Imports have made up the difference. (See data.)

Hogs put on about twice as much weight as cattle per pound of feed, and chickens grow even faster. Smithfield Foods in the United States has become remarkably “efficient” at fattening hogs en masse; such expertise is a big attraction for China. Yet even though the United States has a better reputation on food safety than China, U.S. factory farms have their problems as well in terms of the contamination of meat and the massive quantities of waste generated by large groups of animals. The widespread use of antibiotics in U.S. industrial meat production has been linked to growing bacterial resistance to antibiotic treatment. And one feed additive still used in the United States to help pigs gain lean weight—ractopamine—has been banned in China because of feared negative health effects. According to reporting by Reuters, Smithfield began limiting the use of ractopamine on some, but not all, of its animals last year, with an eye on the Chinese market.

Given the existing land degradation and pollution that are making it harder for China to produce more—and safer—food, it is not difficult to see why foreign acquisition of both land and food producers is becoming increasingly attractive. Yet just as the American diet has been shown to be a dangerous export—accompanied by spreading obesity, heart disease, and other so-called diseases of affluence—ramping up American-style factory meat production is not without risk.

For more information, see “Meat Consumption in China Now Double That in the United States,” by Janet Larsen, and the latest book from Earth Policy Institute, Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity, by Lester R. Brown.

Copyright © 2013 Earth Policy Institute