Space is the place where race, poverty, and the environment get sorted out, for better or worse. And the spaces where we live, work, learn, and play are the places where integration succeeds or fails, argues Sheryll Cashin. The Georgetown University law professor wrote 2004’s The Failures of Integration: How Race and Class Are Undermining the American Dream, one of the most important and provocative books on civil rights in recent years. (Read an excerpt from the book.)

Sheryll Cashin.

Photo: Institute on Race & Poverty.

Like the environmental movement, the civil-rights movement has become too focused on litigation, says Cashin. While legal rights are essential, she says, the most important cause of segregation and poverty in America is the simple fact that even after 50 years of legally enforced integration in the aftermath of Brown v. Board of Education, poor people and people of color still live in spatially isolated communities. Space is the problem. But it could be the solution too.

With information and mapping tools now widely available and accessible online, communities can put all their concerns on the same map. Some are doing just that, and coming up with new solutions for integration and the environment. But to truly integrate what Cashin calls our “life space,” more environmental, civil-rights, education, and economic development organizations need to break out of their own boundaries to integrate the tools and organizing needed to bring people together in a common space.

Cashin spoke to Grist from her home in Shepherd Park, an integrated neighborhood in Washington, D.C.

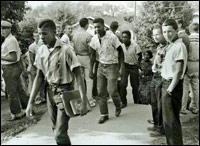

Students approach a newly integrated Tennessee high school in 1956.

Photo: Library of Congress.

People tend to think of the civil-rights movement as one of the great success stories of American history. And yet integration has failed. Why?

The chief gains of the civil-rights movement were that we delegitimated discrimination. The vast majority of Americans now believe that no one should be limited in their access to anything based on race. But the unfinished business of the civil-rights movement is actually ordering our society in a way where people really do have opportunities, so that the vision of an egalitarian society is actually true for people in their daily lives.

The reason it’s not true for people in their daily lives is that we’ve not yet made the advances to date that we should have in housing. We haven’t really opened up our life space to racial and economic integration. There’s a lot of intentional policies, both historic and current, that encourage segregation, exclusion, and homogeneity, instead of integration, heterogeneity, and inclusion. My initial impulse in writing this book was to give up on the integrationist ideal because it is too hard.

What’s so hard?

The hardest question, in my view, is this business of opening up neighborhoods and schools and institutions in a truly inclusive way.

Some of the issues that you see as important — affordable housing, for instance — involve development. Doesn’t this often conflict with environmental goals?

The existing pattern of development, the way the physical space of America is being developed, is in conflict with the goals and aspirations of environmentalism. Frankly, in brutal terms, a lot of what drives sprawled, leapfrog development is white families who want to have this elusive American dream, of a poverty-free, good-school existence, where [their] kids will be free of crime.

I’m not saying people are racist when they make these choices, but I think an increasingly diverse American society, with people who are different, creates fear in a lot of people. And our policies reflect that fear. And sprawl development leads to more people in the car, more auto gas emissions, more eating up of open space and land. And if you are a person who is concerned with sprawl, and if you are a person who is concerned with auto emissions, I think you need to understand that fundamental issues of race relations in this country are part of — not all of, but part of — the impediments to you getting saner public policies adopted. And I think you need to begin to look for allies beyond the environmental community to get you to 51 percent in any policymaking realm, because after all, you’re not going to succeed in your policy agenda until you get to 51 percent.

In an increasingly diverse world, we’re rapidly moving toward the day when we’re going to be a majority-minority America like California and Hawaii are today. If you don’t have the skill sets and the empathy to identify other communities with some potentially common goals and build those coalitions, you’re going to continue to be marginal. You’re going to continue to lose battles. And I’ve got to say, I’m not an active member of the environmental movement. But I consider myself an environmentalist. You know, I care, I recycle, I try not to overuse energy, all those things. But from my perspective, everything I see, the environmentalists are losing. And they’re losing badly. Am I wrong about that?

I don’t think so. So much of your argument seems to come back to schools, and environmentalists traditionally have paid little attention to education. Is there a case for environmentalists getting involved in educational equity and education reform?

Yes. Here’s where the intersection is: much of what fuels suburban sprawl and white flight is the chase for quality schools. There’s a book called The Two-Income Trap that shows there has been a run-up in bankruptcies because two-income families with children have been engaging in these bidding wars to get into the most expensive house they can afford. That fuels this outward development. If we could create more stable racially and economically diverse communities, there would be much less pressure on outward development.

You write that GIS [Geographic Information Systems] is one of the most powerful tools to help people in communities visualize and understand their communities and envision solutions. Could you describe why?

The real expert on this is Myron Orfield, who was a state representative and senator in Minnesota. He got the state to pay for a GIS study to look at where public infrastructure investments were going. They found this general pattern of the favored quarter. Often there will be a quadrant that is overwhelmingly white and affluent that is getting a disproportionate share of public dollars that fuel growth. And middle-income people are actually subsidizing it. And the central city was subsidizing it.

He was able to form a coalition, once he could put the data together, that transcended boundaries of race and class to work together around these interests. They realized [all] of us are in the same boat. They formed a majority in the state legislature. And they passed a series of progressive laws, including a regional authority that had strong powers over land use. It helps a lot when you put objective facts on the table.

If you could set up the perfect mapping tool for communities to grapple with these questions — say a Google Earth that could focus on your community and include all the information you needed to identify problems, ask questions, and brainstorm solutions in a spatially specific environment — what would it look like?

It’s not for me to tell a community what they should be mapping, although I have some ideas. But if you want to build a groundswell, to get hundreds of thousands of people involved, then involve them in identifying the issues that they care about and think ought to be tracked. In Seattle, they track not just school quality and testing, but salmon spawns, and what the salmon population is, air quality, number of units of affordable housing. All of these give you a clear, objective sense of how your community is doing, and you can use that information to bring in allies.

You write about some communities that are already doing this. Which ones inspire you?

Chattanooga, Seattle, a number of communities do this. What inspired me generally was that people who care about sustainable development have been empowered through this. Individuals and organizations found power and allies through this and interconnections. And they relate them back to public policy choices. And that inspires me. Individuals feel powerless to change anything. And if you’re sitting at home, you are powerless. There are mechanisms for making a difference, but you’re going to have to find allies, and find or build institutions or coalitions.

You live in a neighborhood that the Washington Post has described as “fairly well-integrated.” What’s so great about Shepherd Park?

It’s not a perfect community. It is stably integrated. You have mostly whites and blacks living together. It’s integrated down to the neighborhood block level. We are close in to the city. I get to work in 20 to 30 minutes. I can walk from where I am to restaurants and take public transportation to the gym and movies. I live in a beautiful home. The neighborhood is pretty stable. There’s some crime, but not a lot. There are people who are affluent and not affluent. And the public school — I don’t have kids yet, but I’m working on it — it’s a good public school. It could be better. But it’s solid. It works for the kids. And it shows you can live in a diverse society.

How could it be better?

More of the families who are in this neighborhood could send their kids to the public school. In the book, I analogize community to being in a marriage. A marriage is work. You have to work at communication and negotiate differences. It takes people who are committed to moving across boundaries of their race and class.

You were born and raised in Huntsville, Ala. You dedicate The Failures of Integration to your parents, who were political activists. What kind of imagined community did they see for you?

They imagined the community that they created for themselves. My parents were activists, but also members of the Unitarian church, although both became Baptists later. I grew up in a household where the most fascinating people would come through. My parents lived a very diverse life, with friends from a lot of different realms. They modeled for me how they wanted to be in the world. These were two people with very strong black identities. They wanted me to value who I was as a black person and value black institutions, but also not cut myself off from exciting, interesting things.

What would you imagine for your children?

Basically the same. I would like my kids to be able to have a broad array of choices, in terms of living, in terms of schools. I’d like them to go to institutions that actively cultivate diversity, where everyone’s included, so it’s a true community of humanity. It may sound idealistic, but that’s what I hope for.