This story was originally published by Project Earth/Fusion and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Air travel seems to get increasingly unpleasant as time goes by. Tighter security, more passengers, fewer amenities, and additional fees all add up to an often unfriendly experience in the skies (not to mention being forcefully dragged off an overbooked plane). Now, a new study in the journal Climatic Change posits that climate change is going to make this whole endeavor even worse by making it harder for planes to get off the ground.

You may recall earlier this summer when a 120-degree heatwave in the Southwest forced American Airlines to cancel more than 40 regional flights due to dangerous takeoff temperatures. This led to a number of passenger delays and a lot of internet explainers and hand-wringing.

While the heatwave approached record-breaking levels, in the future this type of heat will be more common, and thus more disruptive.

The first global analysis of this impact, the study found that in coming decades during the hottest parts of the day between 10 and 30 percent of fully loaded planes may have to remove fuel, cargo, or passengers — or else wait for cooler hours to fly. Overall, the authors estimate that if greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, payload weights may have to be reduced by up to 4 percent on the hottest days. This would mean removing around a dozen passengers from a 160-seat aircraft, a significant number for an industry operating on razor thin margins. However, if carbon dioxide emissions are significantly reduced, the authors say this impact could be as little as 0.5 percent.

“This points to the unexplored risks of changing climate on aviation,” coauthor Radley Horton, a climatologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said in a statement. “As the world gets more connected and aviation grows, there may be substantial potential for cascading effects, economic and otherwise.”

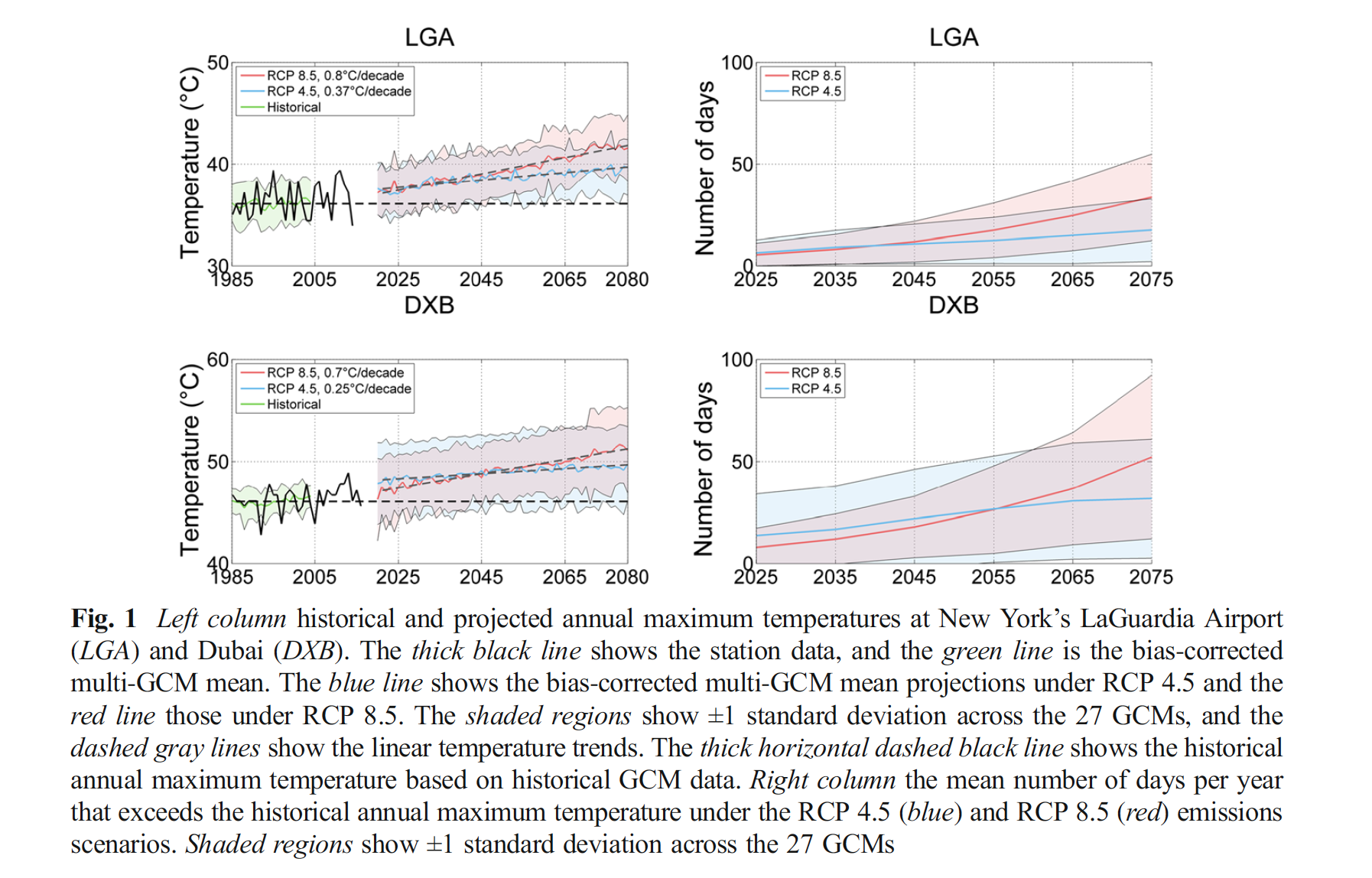

The pain won’t be evenly distributed, and airports with shorter runways and in hotter areas or at higher elevations are likely to suffer more. At New York’s LaGuardia, which apparently has short runways, the authors state that a Boeing 737-800 may have to offload weight half the time during the hottest days. Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, will likely be even worse off, as its long runways will fail to compensate for the intense heat. New York’s JFK, London Heathrow, and Paris’ Charles de Gaulle will likely be less affected thanks to their longer runways and milder climates.

Lead author Ethan Coffel, a Columbia University PhD student, told Project Earth that while aircraft could be modified for better takeoffs in hot weather, more likely “would be rescheduling the most affected flights to cooler hours of the day or potentially extending airport runways.”

Climatic Change

So why do hotter temperatures make taking off harder? The study lays it out simply:

As air warms, it spreads out, and its density declines. In thinner air, wings generate less lift as a plane races along a runway. Thus, depending on aircraft model, runway length, and other factors, at some point a packed plane may be unable to take off safely if the temperature gets too high. Weight must be dumped, or else the flight delayed or canceled.

Weather is already a major challenge for flyers. Snow storms, high winds, and other unpleasant forecasts can cause major delays and cancellations that cascade across the aviation system, leaving passengers upset and stranded in their wake.

Not only will climate change make taking off harder, but it is going to increase the instances of severe weather events, such as heavy rains, that are known to disrupt fights. Sea-level rise will also creep up on a lot of coastal airports, causing costly airport repairs or even relocations. And turbulence is forecast to get worse, too.

Meanwhile, in typical climate change ironic fashion, air travel is becoming a greater and greater contributor to planet-warming emissions. Right now, the global aviation industry is responsible for about 2 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, with the U.S. accounting for nearly 30 percent of this total. But as other countries rapidly expand their commercial flight infrastructure the industry will continue to grow at breakneck speed for the foreseeable future. In fact, aircraft emissions are expected to grow by 50 percent by 2050. Meanwhile, efforts to reign in associated emissions are slow moving and largely toothless. However, new, more efficient technologies that cut back on fuel use could also save airlines a lot of money, the the incentive is there — although major reductions will be extremely technologically challenging.

Only just last year did the Environmental Protection Agency declare jet engine exhaust to endanger public health due to its contribution to climate change. At that time, regulating jet emissions was seen as just one element of the Obama administration’s goal under the Paris climate agreement to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by up to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025.

Well, in the ensuing year, climate change deniers have occupied the presidency and the top position at the EPA, and the U.S. is now on track to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. With Trump and Scott Pruitt in charge, whatever regulations were in store are likely to slow to a crawl.

Long gone are the days when someone like Janet McCabe, EPA’s former Acting Assistant Administrator for Air and Radiation, could say things like:

Addressing pollution from aircraft is an important element of U.S. efforts to address climate change. Aircraft are the third largest contributor to GHG emissions in the U.S. transportation sector, and these emissions are expected to increase in the future. EPA has already set effective GHG standards for cars and trucks and any future aircraft engine standards will also provide important climate and public health benefits.