North Carolina is home to 31 coal ash pits where Duke Energy stores an estimated 111 million tons of toxic waste produced by coal-fired power plants. The state is also home to thousands of manure pits, known euphemistically as “lagoons,” which hold approximately 10 billion pounds of wet waste generated each year by swine, poultry, and cattle operations.

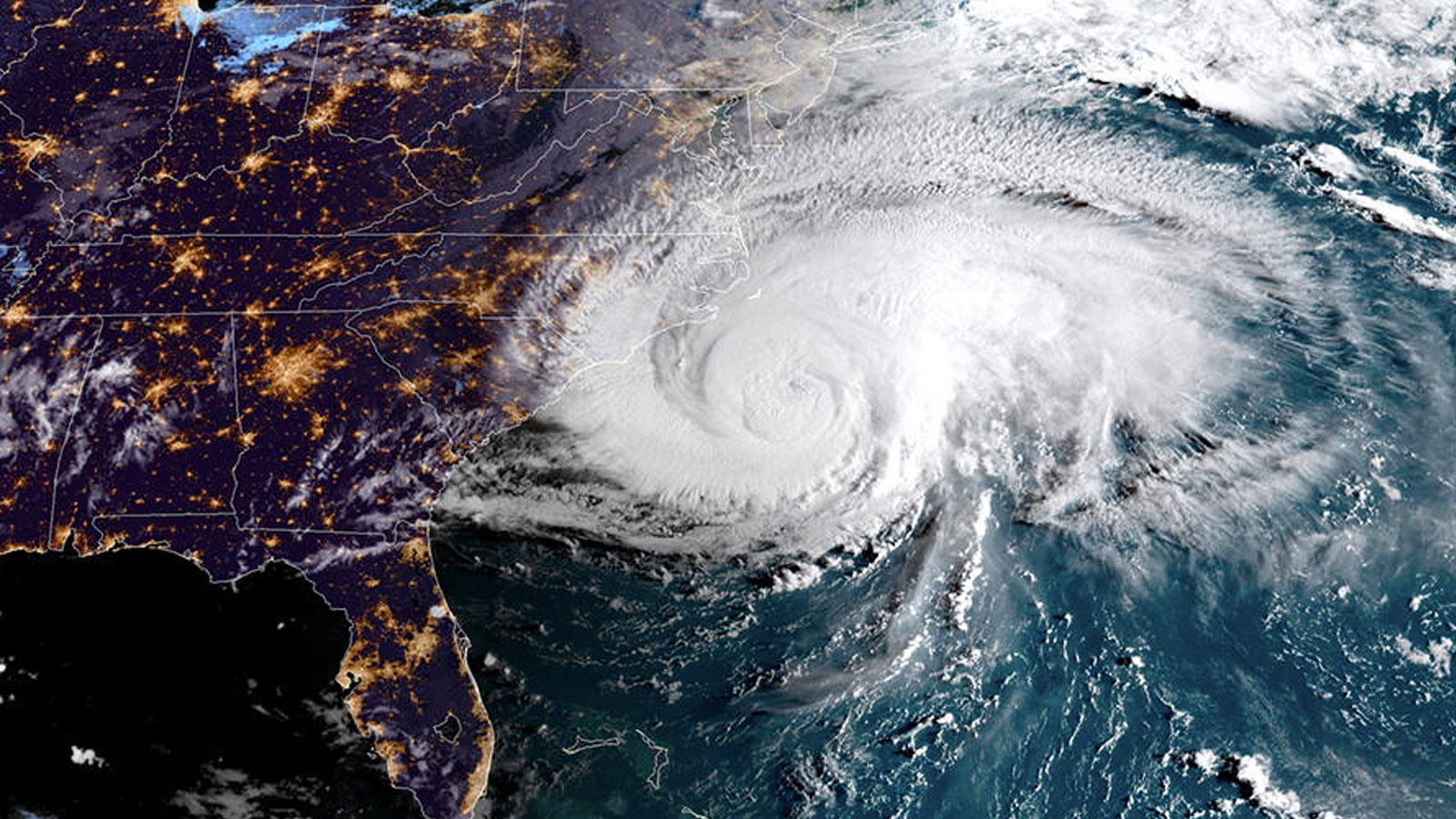

A handful of news outlets are reporting about the danger of coal ash and hog manure spilling into North Carolina’s waterways in the wake of Hurricane Florence. Bloomberg covered the serious environmental and public health risks and the Associated Press warned of a potential “noxious witches’ brew of waste.”

There’s precedent for these concerns. In 1999, Hurricane Floyd, which struck North Carolina as a Category 2 storm, washed 120 million gallons of hog waste into rivers, Rolling Stone later reported. As AP noted this week, that was just one part of the mess caused by Floyd:

The bloated carcasses of hundreds of thousands of hogs, chickens and other drowned livestock bobbed in a nose-stinging soup of fecal matter, pesticides, fertilizer and gasoline so toxic that fish flopped helplessly on the surface to escape it. Rescue workers smeared Vick’s Vapo-Rub under their noses to try to numb their senses against the stench.

The media has been amping up its coverage of potential Hurricane Florence damage. But so far they’re missing an important part of the story — that African-Americans and other communities of color could be hit particularly hard by the resulting pollution. They’re also failing to note how the Trump administration has been loosening regulations and oversight in ways that could make coal ash and hog-waste spills more likely.

There’s an environmental justice component to this story

After Floyd, North Carolina taxpayers bought out and closed down 43 hog factory farms located in floodplains in order to prevent a repeat disaster. But when Hurricane Matthew hit the Carolinas as a Category 1 storm in 2016, at least 14 manure lagoons still flooded.

Even if they’re not widespread, hog-waste spills can still be devastating to those who live nearby — and many of the unfortunate neighbors are low-income people of color.

Two epidemiology researchers at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill published a paper in 2014 with a very straightforward title: “Industrial Hog Operations in North Carolina Disproportionately Impact African-Americans, Hispanics and American Indians.” They wrote, “Overflow of waste pits during heavy rain events results in massive spills of animal waste into neighboring communities and waterways.”

A Hurricane Floyd-flooded hog waste lagoon. JOHN ALTHOUSE / AFP / Getty Images

Tom Philpott explained more about that research in Mother Jones in 2017:

As the late University of North Carolina researcher Steve Wing has demonstrated, [North Carolina’s industrial hog] operations are tightly clustered in a few counties on the coastal plain—the very part of the state that housed the most enslaved people prior to the Civil War. In the decades since, the region has retained the state’s densest population of rural African-American residents.

Even when hurricanes aren’t on the horizon, activists are pushing to clean up industrial hog operations. “From acrid odors to polluted waterways, factory farms in North Carolina are directly harming some of our state’s most vulnerable populations, particularly low-income communities and communities of color,” Naeema Muhammad of the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network said last year.

Poor and rural communities of color are heavily affected by coal ash dumps as well. The New York Times reported last month on an environmental-justice campaign against coal ash pollution in North Carolina. Lisa Evans, a lawyer with the environmental group Earthjustice, told the Times, “Coal ash ponds are in rural areas, particularly in the Southeast. Those communities have less power and less of a voice.”

The Trump administration recently loosened coal ash rules

The first major rule finalized by Andrew Wheeler, acting head of the Environmental Protection Agency, loosened Obama-era requirements for coal ash disposal. The change, which will save industry millions of dollars a year, could lead to more dangerous pollution. The Washington Post reported about this in July:

Avner Vengosh, a Duke University expert on the environmental impacts of coal ash, said that scaling back monitoring requirements, in particular, could leave communities vulnerable to potential pollution.

“We have very clear evidence that coal ash ponds are leaking into groundwater sources,” Vengosh said. “The question is, has it reached areas where people use it for drinking water? We just don’t know. That’s the problem.”

The Trump administration is also going easy on factory farms like the industrial hog operations in North Carolina. Civil Eats reported in February that there’s “been a decline in the number of inspections and enforcement actions by the [EPA] against concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) since the final years of the Obama administration.” Last year, more than 30 advocacy groups filed a legal petition calling on Trump’s EPA to tighten rules to protect communities from factory farms.

North Carolina Republicans aren’t helping things either — they’ve gone easy on coal plants and hog operations. And in 2012, the GOP-controlled state legislature actually passed a law banning state officials from considering the latest sea-level rise science when doing coastal planning. ABC reported on the development at the time:

The law was drafted in response to an estimate by the state’s Coastal Resources Commission (CRC) that the sea level will rise by 39 inches in the next century, prompting fears of costlier home insurance and accusations of anti-development alarmism among residents and developers in the state’s coastal Outer Banks region. …

The bill’s passage in June triggered nationwide scorn by those who argued that the state was deliberately blinding itself to the effects of climate change. In a segment on the “Colbert Report,” comedian Stephen Colbert mocked North Carolina lawmakers’ efforts as an attempt to outlaw science.

“If your science gives you a result you don’t like, pass a law saying the result is illegal. Problem solved,” he joked.

As Hurricane Florence bears down on North Carolina, journalists should make sure that their stories include the people who will be hurt the most by waste spills and other impacts, as well as the businesses and lawmakers who have been making such environmental disasters much more likely to occur.

Lisa Hymas is director of the climate and energy program at Media Matters for America. She was previously a senior editor at Grist.