Coral reefs cover just 0.1 percent of the ocean floor, but provide habitat to 25 percent of sea-dwelling fish species. That’s why coral scientist C. Mark Eakin, who coordinates the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coral Reef Watch program, is surprised that the warning he has been sounding since last year — that the globe’s corals appear to be on the verge of a mass-scale bleaching event — hasn’t drawn more media attention.

Bleaching happens when corals lose contact with zooxanthellae, an algae that essentially feeds them nutrients in symbiotic exchange for a stable habitat. The coral/zooxanthellae relationship thrives within a pretty tight range of ocean temperatures, and when water warms above normal levels, corals tend to expel their algal lifeline. In doing so, corals not only lose the brilliant colors zooxanthellae deliver — hence, “bleaching” — but also their main source of food. A bleached coral reef rapidly begins to decline. Coral can reunite with healthy zooxanthellae and recover, Eakin says, but even then they often become diseased and may die. That’s rotten news, because bleaching outbreaks are increasingly common.

Before the 1980s, large-scale coral bleaching had never been observed before, Eakin says. After that, regionally isolated bleaching began to crop up, drawing the attention of marine scientists. Then, in 1998, an unusually strong El Niño warming phase caused ocean temperatures to rise, triggering the first known global bleaching event in the Earth’s history. It whitened corals off the coasts of 60 countries and island nations, spanning the Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Red Sea, Persian Gulf, Mediterranean, and the Caribbean. We functionally “lost between 15 percent and 20 percent of the world’s coral reefs” in ’98, Eakin said. Only some have recovered.

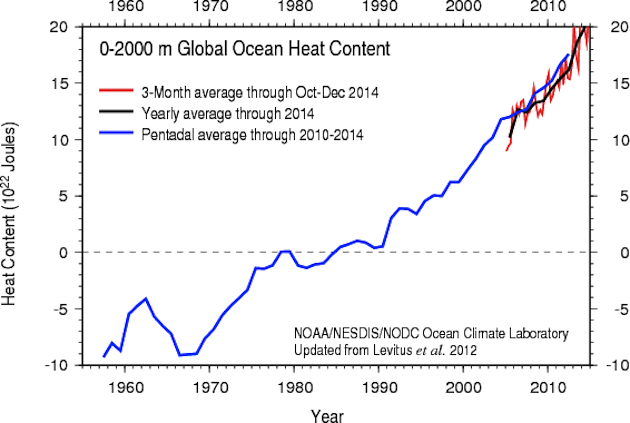

Eakin is concerned about a relapse, because the oceans are relentlessly warming, driven by climate change from ever-increasing greenhouse gas emissions. As heat builds in the ocean, he says, corals become more vulnerable to bleaching.

NOAA

As a result, it no longer takes a classic strong El Niño to cause warming and trigger mass bleaching. This current El Niño, after starting strong last year, has essentially collapsed, in what Eakin calls a “highly unusual” pattern. Even so, the northeast Pacific is experiencing “very warm” water, he said. Overall, the oceans’ waters have warmed so much in recent years that most coral areas are “right on the verge of having enough heat stress to cause bleaching and it doesn’t take nearly as much to start one of these global-scale events,” he said. Since 1998, there have been two major beaching events, neither driven by a strong El Niño. In 2005, the Caribbean ocean experienced its worst-ever bleaching event despite a relatively tame El Niño year, and in 2010, the second-ever globe-spanning bleaching event occurred, again during a mild El Niño. It wasn’t as severe as the 1998 disaster, but unlike the earlier one, it “didn’t have a strong El Niño driving it,” Eakin says.

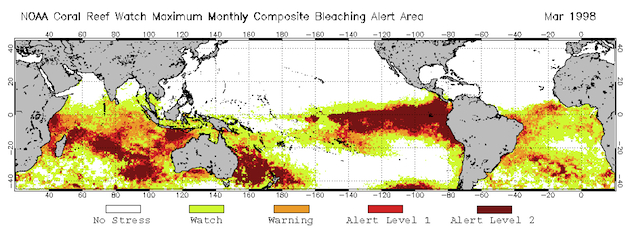

Which brings us to 2015. During our phone conversation, Eakin directed me to this page on NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch site. He asked me to consider the below chart, which shows the water-temperature patterns that prevailed in spring ’98 — bleaching was most severe where the color is darkest red, signifying the most severe warming.

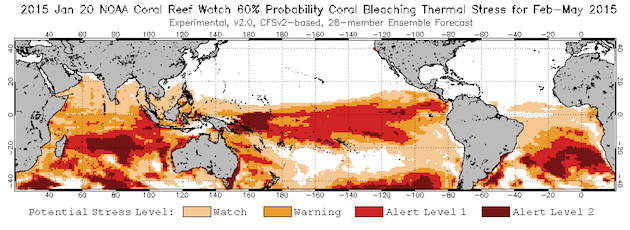

Then he directed me to the latest NOAA analysis, taken this month, that forecasts warming patterns four months into the future.

He called the warning currently happening in the Indian Ocean (the one on the left in the above charts) “amazingly similar” to the situation in ’98, which foretells a warming pattern that could subject corals to a ’98-scale bleaching crisis. “If you look at where we were in 1998 and look at where we are now, you see that the ocean is primed to respond with a sustained high temperature during the warm season in a way that previously took a big El Niño, and now doesn’t,” he said.

Again, a mass bleaching doesn’t translate directly to mass coral die-off, because corals can recover. But the recovery takes decades — large corals grow about 1 centimeter per year, Eakin says — and the bleaching events are coming faster and faster, each one stalling recovery and causing new damage. The emerging pattern for large-scale events looks like this: 1998, 2005 (confined mainly to the Caribbean), 2010, and now, quite possibly, 2015.

And another facet of climate change makes recovery even more difficult, Eakins added: acidification, which comes about as the oceans sponge up more and more carbon from the atmosphere. Heightened acidity makes it harder for corals to absorb the calcium carbonate they need to build and maintain their skeletal structure.

Eakin says it will take major action to reverse climate change to save the globe’s coral reefs. Currently, carbon dioxide makes up nearly 400 parts per million of the atmosphere, and for corals to thrive, we’ll need to throttle that back to 350 ppm or possibly even 320 ppm, he said. Those are ambitious goals. Making corals resilient enough to survive until we can manage to do that, he added, will require taking action against “local stressors” that also harm them, like overfishing and pollution.

“People say corals are the rainforests of the sea. But coral reefs are more biodiverse than rainforests,” he said. “It ought to be the other way around: Rainforests are the coral reefs of the land.” And these glorious cradles of oceanic life aren’t getting any stronger. “The punch that knocks a boxer out in the ninth round doesn’t have to be as hard as the punch that would knock him out in round one,” Eakin said.

This story was produced by Mother Jones as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced by Mother Jones as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.