Elliot Diringer, a veteran environmental journalist and a deputy press secretary in the Clinton White House, is now director of international strategies at the Pew Center on Global Climate Change. The center is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to providing credible analysis and innovative solutions to address climate change.

Tuesday, 17 Jul 2001

BONN, Germany

It’s a fair bet that many in the diplomatic horde converging on Bonn for the latest round of global warming talks would rather be somewhere else.

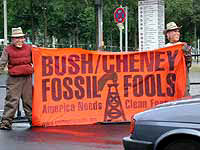

Banner at a protest outside yesterday’s talks.

Photo: Independent Media Center.

In the past when they’ve gathered, the government negotiators charged with forging an international strategy against climate change could usually expect to produce enough forward movement, however incremental, to go home declaring success. Until, that is, the unsettling impasse last fall in The Hague, where tough decisions were due but longstanding differences proved too difficult to bridge.

This time around, the outlook is gloomier still. Indeed, “success” in Bonn might best be defined as averting an outright collapse.

Nearly a decade ago, at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, nations committed themselves ever so tentatively to the fight against global warming. I covered that heady affair as a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle. Five years later, having just joined the environmental policy office in the Clinton White House, I was a U.S. delegate to the historic Kyoto conference, where industrialized nations went the next step, pledging to finally start taking real steps.

Now I come as an “observer” representing the Pew Center on Global Climate Change, an independent nonprofit that is part think tank, part catalyst for corporate action against global warming. My first observation is not a cheery one: Nearly a decade after the search began, the formula for mobilizing a genuine global effort against our greatest environmental threat seems as elusive as ever. Apart from the raft of high-stakes issues still dividing countries, the world’s largest emitter, the U.S., has now renounced the Kyoto Protocol, declaring it “fatally flawed.”

The official conference agenda calls for picking up where The Hague left off. Negotiators will again spend long, tedious hours haggling over the issues that bedeviled them last time: Should nations be forced to achieve most of their emission reductions at home, or be free to purchase all the emission credits they want from countries with spare ones to sell? How much credit should be allowed for carbon sucked from the atmosphere by forests and farms? How much money will rich countries provide poor countries to help them cope with and combat global warming?

But the real questions looming over the resumed Sixth Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change are more basic: With the United States now refusing to go along, is the rest of the industrialized world still prepared to continue down the path charted in Kyoto? And if not, what is the alternative?

Dreary prognosis, colorful critical mass ride in Bonn.

Photo: Independent Media Center.

Chances are that when weary negotiators head home 10 days from now, those questions will be left begging. Barring an unexpected turn of events — say, a sudden breakthrough when G8 leaders gather later this week in Genoa — there will be no decisive outcome to COP6. Europeans will be unable to persuade Japan to join them right now in an unequivocal embrace of Kyoto, providing the critical threshold to put the treaty into effect. Ministers will speechify and take stock, then jet back to their capitals to weigh options for the next round, this October in Marrakech.

This dreary prognosis, particularly when set against the growing scientific certainty that global warming is already upon us, might all too easily be cause for despair. I prefer the long view.

An effective global response to climate change would, if mounted, be the largest experiment in directed change ever undertaken. It would shape countless policies, investment decisions, and technology choices for decades to come, with the goal of gradually weaning industrialized nations from fossil fuels, and keeping the booming developing world from becoming ever more dependent. The challenge is unprecedented, and getting 180 nations to agree on the best way to meet it may well be the greatest diplomatic feat ever attempted.

For all the recent setbacks, there are in fact encouraging signs. Even without a global framework, many nations, both developed and developing, have begun taking concrete steps to curb their emissions. The public and press are more attuned than ever. And the corporate community, which at the time of the Kyoto in 1997 was still in deep denial, is coming around. Major companies like those we work with at Pew are taking, and demanding, real action.

But this momentum, however modest, will be lost unless nations commit themselves to mandatory action with legally binding targets. That was the premise going into Kyoto, and for all the negotiations since. But in rejecting the Kyoto, the U.S., for now at least, rejected that basic premise as well.

Japan still holds out hope of luring the Bush administration back to Kyoto; the European Union favors forging ahead with or without the U.S. The U.S., having offered no alternative or even saying when it might, has promised not to stand in the way. “If other countries want to shoot themselves in the foot,” one American official told me, “they’re welcome to.”

Unless the U.S. offers up a credible alternative, and does it soon, the best course may well be for other countries to settle outstanding differences and make Kyoto real. These two weeks in the city by the Rhine will, hopefully, give us a clearer picture of whether that’s possible — or whether it’s time to contemplate other paths forward.

Either way, our ultimate goal must remain the same: an international agreement that includes all the major emitters and delivers real reductions in greenhouse gases at a price the world can afford. It’s a tall order. But it’s why we’re here.

Wednesday, 18 Jul 2001

BONN, Germany

I can say from experience that anyone representing the U.S. at international climate negotiations has to be prepared to be cast as the villain — sometimes unfairly, but not always without cause.

Being the world’s largest climate polluter makes the U.S. an easy target. Over a decade of negotiations, it has also put the U.S. at the center of action, whether blocking binding emission targets when the first climate treaty was forged in 1992 in Rio, or contributing some of the best features of the Kyoto Protocol when it was negotiated five years later.

But as countries meet here in Bonn to try again at making Kyoto real, the dynamic is very different. The U.S. continues to cast a long shadow, and draw blame. But it’s not nearly the presence it once was.

Activists in Bonn poke fun at the Bush administration.

Photo: Greenpeace.

The big difference, of course, is the Bush administration’s renunciation of the Kyoto Protocol. As the self-declared pooper at this latest Kyoto party, the United States is wisely keeping a lower profile. It is fielding a m

uch smaller delegation than in the past and has dispensed with daily press briefings. Still, as negotiators haggle behind closed doors, American diplomats are not simply sitting on the sidelines.

Despite rejecting Kyoto, the U.S. remains a party to the Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiated (and signed by George Bush the Elder) in Rio — the foundation for all the bargaining that has taken place since. And the negotiating agenda here actually is a mix of “Convention” issues and others relating specifically to Kyoto. U.S. negotiators are engaging directly on the former, while approaching the latter a bit more gingerly.

The Convention issues relate largely to developing countries and how the developed countries will deliver the technology and financial assistance promised them in Rio. Negotiators have just started on the thorniest of those issues — a proposal for industrialized countries to provide developing countries with $1 billion a year in new aid. The U.S. would pay roughly 40 percent (its contribution to greenhouse gas emissions in 1990), a sum it’s not about to fork over.

On the Kyoto issues, the U.S. has promised it’s not here to obstruct. But U.S. negotiators are speaking up, sometimes forcefully, when they feel it’s necessary to “protect U.S. interests.” They define these interests largely as guarding against legal precedents that could affect future treaties on other matters. For instance, the U.S. opposed a proposal that would give developing countries a majority of seats on the board overseeing Kyoto enforcement, fearing it could serve as a model for future bodies.

This highly selective approach to negotiating has left traditional U.S. allies frustrated. The U.S. customarily negotiates as a bloc with other “Umbrella Group” countries — Japan, Canada, Australia and other industrialized nations outside the European Union. Without the full engagement of its biggest partner, the group is now less coordinated and, consequently, wields less clout

“One of our biggest problems right now,” complained a Canadian delegate, “is that the most important member of the Umbrella Group is only there part-time.”

Many in industry also miss a stronger U.S. voice. Companies that may be affected by Kyoto whether or not the U.S. is a party — for instance, those operating or competing abroad — have in the past counted on the U.S. to ensure that the treaty’s rules would be reasonable. Some industry representatives meeting with the U.S. delegation last night urged it to get more engaged on issues like emissions trading and carbon sequestration. “I don’t understand why we’re just sitting there quietly,” one representative said testily.

“The president has made clear that the United States does not support the Kyoto Protocol,” responded a lead U.S. negotiator, “and we are not going to be dragged back into it.” Besides, he added, when it comes to shaping a treaty, an avowed non-party is not likely to have much credibility with other countries.

Environmentalists, meanwhile, worry that the U.S. may be all too engaged. Watching for bad precedents, they fear, will prove to be legalistic cover for a stealth attack on Kyoto. “It gives them carte-blanche to try to block anything they see fit,” said Kailee Kreider of the National Environmental Trust, a Washington-based advocacy group.

Asked by the press today about the U.S. role, conference Chair Jan Pronk voiced no complaints. “The United States is not — I repeat not — obstructing,” he said. “They are constructively participating in the negotiations.” Still, the divisions among other countries remain deep and numerous. So little headway was made in the first two days that Pronk canceled an open plenary session Tuesday night in which negotiators were to report on their closed-door talks.

Ultimately, how the U.S. behaves here on nitty-gritty issues may have little bearing on whether the international community can mount an effective response to climate change. Kyoto’s fate will likely remain an open question at least until the next round, this October in Marrakech. Hopefully by then, the U.S. will have told the rest of the world how it would like to proceed, and other nations can decide whether to join it, stick with Kyoto, or find another way forward.

U.S. negotiators may never be able to shake the role of villain. But maybe by the time of Marrakech, they’ll at least be ready to play.

Thursday, 19 Jul 2001

BONN, Germany

About a year ago, Bob Page and his wife were hiking high in the Canadian Rockies in an area they had last visited 10 years before. Approaching a vast expanse of ice known as the Saskatchewan Glacier, they were stunned by what they saw.

“The glacier had retreated about a kilometer,” he told me. “Suddenly, there was a new valley there we hadn’t seen before. That sight was just so powerful.” Page knew instinctively that he was viewing stark evidence of global warming.

Today, Page is hiking the corridors of a stuffy conference center half a world away. He is one of the thousands gathered here in hopes of resuscitating the global drive to keep the world’s glaciers intact and avert the many other threats posed by our planet’s warming.

Chair Jan Pronk speaks in the conference center in Bonn.

Photo: Greenpeace.

Page, however, is not part of the army of environmental NGOs whose representatives routinely buttonhole negotiators and issue press statements hounding governments to action. He is a company man, a vice president for the Canadian-based TransAlta Corp., one of North America’s largest emitters of greenhouse gases.

His message, nonetheless, is much the same: Serious consequences await us unless governments and businesses alike get down to the job of protecting our climate. TransAlta, Page said, is fully committed to doing its part. The electric power provider, which generates much of its energy by burning coal, has set a goal of reducing net carbon emissions from its Canadian operations to zero by 2024.

Claims of corporate commitment to the environment are often greeted with skepticism by greens and the public, frequently with good reason. But one of the most profound shifts in the climate debate in recent years is the emergence of leading corporations that don’t simply talk the talk — they are also taking concrete steps to cut emissions and calling on governments to step up their efforts.

To be sure, there are powerful corporations that continue to dispute the scientific evidence of climate change and oppose real efforts to address it. Their views seem to hold sway at the highest levels in Washington. But a growing number of others, including TransAlta and 35 other major corporations we work with at the Pew Center on Global Climate Change, are stepping up to the climate challenge.

Many of them are here pressing their case. They want a strong international agreement that sets binding targets for reducing emissions. They also want clear, sensible rules that allow for emissions trading, carbon sequestration, and other creative approaches that will enable countries and companies to meet those targets without sending economies or profits into a tailspin.

As ministers arrived here today, and the talks turned from “technical” to “political” issues, the odds still appeared low for such an agreement being struck here in Bonn. The goal is to agree on rules for implementing the Kyoto Protocol so countries can weigh ratifying the treaty, even though the U.S. has rejected it. While negotiators reported progress on some issues, big differences remain on the tougher ones and, in some cases, positions appear to be hardening.

Companies are addressing climate change for a host of reasons. Many are taking a long-term strateg

ic view — picturing how the world will look decades from now and how they can best position themselves in it. Some, like major insurers, see enormous risk from the potentially catastrophic impacts of a warming climate. Some companies see profit potential in marketing renewable energy and energy-saving technologies, or in becoming brokers in the emerging emissions-trading market. Some simply accept that mounting scientific evidence and public pressure will eventually lead to stiffer government controls. After three decades of environmental wrangling, these companies have learned that they’re better off engaging early to help shape rules that are both effective and workable.

TransAlta is counting on good rules to help meet its zero-emissions target. Although the company is investing in renewable energy and new technologies to capture and bury carbon from the coal it burns, its strategy depends heavily on “offsets” — essentially, paying for actions to reduce or avoid carbon emissions elsewhere as a way of compensating for its own releases.

In one of its more novel projects, TransAlta is supporting a company in Uganda that will market a feed supplement to help cattle digest their food better. Healthier cattle not only produce more and better meat and milk, but they also emit less methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. TransAlta is also one of the pioneers in emissions trading, forging the first trans-Atlantic carbon trade last year with a German electric firm.

But the company will not get emissions “credit” for such transactions unless governments agree on rules for trading and other offset mechanisms. “Unless the market mechanisms are in place,” said Page, “it just won’t happen.”

Even as governments waver, however, financial markets are beginning to recognize the long-term risk of rising carbon emissions and reward companies taking steps to minimize them. Earlier this year, Page said, stock analysts quizzed TransAlta on its carbon outlook. “This was the first time in history we’d been questioned by analysts on our policies in this area,” he said.

Failure here in Bonn will be disappointing, but it will not deter TransAlta from its carbon-cutting strategy, according to Page. “A global agreement of some kind is very important to us as a company,” he said. “If Kyoto does not survive, we hope the son or daughter of Kyoto will emerge soon.”

Friday, 20 Jul 2001

BONN, Germany

After four days of slogging through dense text, clearing away underbrush, and settling some of the simpler issues before them, climate negotiators today got down to the real business at hand. And while no one with any sense would predict the outcome, it was possible for the first time in a long while to detect a few glimmers of hope.

“We’re making a little progress. Sneaking forward,” a senior Chinese diplomat told me smilingly during a break in negotiations.

On all the key issues — how much emissions-cutting credit countries can claim for carbon soaked up by soils and trees; whether the international market in emission credits will be free or capped; how rich countries will help poor countries address climate change — major gaps remained.

But lots of subtle signs (something about the body language, if you will) suggest that this time negotiators would much rather go home with a deal.

The tactics and tone are not like those at the deadlocked talks last fall at The Hague. Negotiators are not throwing up all sorts of procedural objections just to keep the talks from going forward. When ministers took the podium yesterday at the start of the high-level segment of the talks, their speeches focused more on positions, with less of the posturing and vitriol seen in the past.

“Everyone was on very good behavior,” said Tom Jacob of DuPont, a veteran observer of climate negotiations. “They were going out of their way not to be offensive while still staking out their positions. There was a remarkable degree of diplomacy.”

Diplomacy, of course, is what these gatherings are supposed to be about. But climate change, an issue that literally implicates every nation on earth, poses more than the usual challenges of treaty-making. It calls for near-term action to avert a long-term threat, something difficult enough for one government, let alone 180. Technically, the issues are complex — frankly, impenetrable to the uninitiated. The economic stakes are high. And the debate is fraught with all the pent-up tensions between the North and the South.

What’s more, each delegation must calculate not only how its position will be received by counterparts here, but, perhaps more important, how it plays at home — how it bears on the next election, the domestic economy, the national budget, and the president’s or prime minister’s standing in the polls.

So it is no surprise that these affairs are chaotic, unwieldy, and not prone to success. The process itself is mysterious, and often the focus of intense debate. At the outset this morning, the way forward was so unclear that the official printed agenda said simply: “Programme to be determined.”

By early afternoon, the parties agreed on how to proceed. They anointed a “small” group of 35 with a set number of seats at the table for each of the negotiating blocs, including the European Union, the Umbrella Group (the U.S., Japan, and other developed countries outside the EU), and the G77, which represents developing countries. For each seat at the table, each bloc was allowed two additional observers.

The plan was for this group to meet behind closed doors, surfacing periodically to report on progress or lack thereof, and leaving thousands of other delegates, observers, and press to mill about, swapping rumors and business cards.

Although the atmosphere inside the talks has been subdued, activists outside have tried to brighten things up.

Photo: Greenpeace.

Photo: Greenpeace.

The atmospherics here are somewhat more subdued than at past climate conferences, in part by design. The center of activity is the glitzy Maritim Hotel, where participants must show conference badges and pass through metal detectors in order to enter. Inside, climate junkies hobnob while keeping watch for key delegates who might actually know what’s going on. But this time, booths where organizations like mine ordinarily distribute literature and show the flag are not allowed, perhaps to minimize distractions so delegates can stay focused on their work. Police barricades ring the hotel, and vans crammed with bored officers and riot gear are parked at strategic spots.

Press operations are housed several hundred yards away. So are the offices of the many environmental organizations represented here, perhaps to avoid an unseemly spectacle like the one at The Hague, where as the talks collapsed, spokesmen for competing green camps jumped atop tabletops in the conference hall, trying to drown out one another as they spun the press.

The groups can stage their protests — this morning, a parade of polar bears struggled to unfurl a banner as delegates arrived — but only from a safe distance.

Back in the Maritim, some delegates suggest that the best possible outcome here is a partial agreement that at least keeps things moving forward. But the hope is that by Sunday night or Monday morning the group of 35 will reach agreement on all the key issues on implementing the Kyoto Protocol. Ministers would then bless the package and head home, leaving their teams to convert the broad outlines into painstaking text. This, in turn, would have to be formally approved, probably at the next round of negotiations this October in Marrakech.

Then countries would ratify the protocol — President Bush has made clear that the U.S. would not be among them — and Kyoto would be a real working treaty.

Given how long it’s taken negotiators to get not very far, it might seem highly implausible that in a mere 48 hours a grand deal could be struck. But as demonstrated in the final chaotic hours in Kyoto, if everyone really does want to get to yes, it can be done.

That’s the optimistic scenario, anyway. Check back to see how things really turn out.

Monday, 23 Jul 2001

EN ROUTE FROM BONN, Germany

I was working the cell phone from the backseat of a Mercedes cab rushing to the airport a few hours ago, and, suddenly, I was struck by the spirit of the scene I’d just left behind.

Moments earlier, a beaming Jan Pronk had slammed down his gavel to seal a deal keeping the Kyoto Protocol alive. A hall full of exhausted delegates (some had haggled through the night, while others draped the floor and couches of the Maritim’s smoky corridors) exploded in applause. Against all odds, Pronk’s idiosyncratic brand of diplomacy had managed to move nearly the entire world forward in the fight against global warming.

I couldn’t help but think back eight months to a very different scene in The Hague, where Pronk’s earlier efforts as conference chair had ended in acrimony and despair. I was with the U.S. delegation at the time, and while virtually no one was faultless in the failure there, I hadn’t felt particularly proud about the part we had played.

The events of the intervening months have left me more troubled than ever about America’s “contribution” to what so obviously must be a global effort to stem a global threat. The events of this morning provide a powerful balm. Despite my government’s refusal to lead or even go along, the rest of the world, for now at least, has resolved to push ahead.

In the plenary hall, ministers were still taking turns congratulating one another and reciting the many challenges yet ahead. But I couldn’t stay. It’s my son’s birthday tomorrow and I don’t want to miss it. So I grabbed a cab and dialed reporters while cruising down the Autobahn for Cologne, lending my voice, and that of my organization, to the worldwide declaration of success.

Now I’m 35,000 feet over the northern Atlantic, halfway home. Out the window of the 747, I can see the gleaming glaciers of Greenland, so vast and remote, and seemingly impervious. Looking down, I wonder how much they’ve retreated since we began tinkering with the chemistry of our atmosphere. I’m reminded that in the race against global warming, we’ve barely begun.

Kyoto, the imperfect instrument that might finally mobilize our efforts, remains a work in progress. Nations drew the basic outlines four years ago in Japan. In Bonn, they filled in the broad brushstrokes. Later this year in Marrakech, they must add the finishing touches. The goal is ratification by enough countries to put the treaty into effect by the time of Rio+10, a major environmental summit late next year in Johannesburg.

Given the extraordinary array of complexities and competing interests, getting Kyoto up and running would be a remarkable achievement. But it would be only a start. Kyoto promises just a fraction of the reduction in greenhouse gases that ultimately is needed to avert climatic disaster. And it offers no real strategy to bring on board the developing countries, whose growing prosperity and populations could completely overwhelm even the most strenuous efforts of industrialized nations.

There remains also, of course, the matter of the U.S. There are all sorts of ironies in today’s outcome in Bonn. This is a deal that, in most major respects, would have satisfied U.S. negotiators in The Hague. In other words, now that the U.S. has renounced Kyoto, other nations are willing to make the concessions that conceivably might have kept us on board.

Although some of those who counseled President Bush to reject Kyoto no doubt hoped to deliver the treaty a fatal blow, their advice may well have had the opposite effect. In unilaterally proclaiming its own response — an emphatic no — the administration cast in stark relief a legitimate question: Is Kyoto the way forward? With the taste of failure still fresh from The Hague, and with a decade of diplomacy at stake, the rest of the world decided the only possible answer was an equally emphatic yes.

8T?ly, the 178 countries that backed the treaty did it in a way that leaves the door open for the U.S. to come back. The particulars of how that could be done may be negotiated in due time. What’s more critical right now is that the U.S. begin genuine efforts at home to curb its soaring greenhouse gas emissions. Here, too, the administration appears to have inadvertently created new momentum. All sorts of bills are being drafted on Capitol Hill, and the prospects for action have never been better. Who knows? By this time next year, Bush might be signing legislation that finally puts the U.S. on the path to climate protection.

My son Ty was barely a year old when I flew off to Rio to cover the Earth Summit, the conference where the international effort against global warming first took shape. Tomorrow, he turns 10. We’ve made some headway. I’d like to think that by the time he turns 20, we’ll have made a whole lot more.