With the release of the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report, the debate over climate change has noticeably shifted from arguments about the reality of human-induced climate change to a debate over how to address the problem.

For example, here on Gristmill an interesting debate has broken out over whether a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system is best to price carbon emissions (e.g., here or here or here). This is exactly the kind of thing we need to be debating, and I’m glad to see it.

Given that climate change is a serious risk, what prudent actions should we take to head off that risk? Below, I lay out the five elements of a successful strategy (summarized from a long discussion in chapter five of my book on climate change).

1. A long-range goal. An effective mitigation program needs a long-term goal to motivate action. For example, if we decide we want to limit global temperature increases to 2-3 degrees C, then (given mid-range estimates of climate sensitivity) we need to stabilize CO2 at 500-550 ppmv.

Given this long-term goal, we can determine the lowest cost emissions pathway to get to that stabilization level:

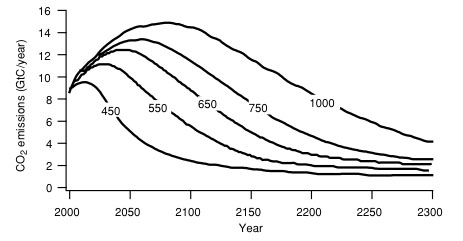

CO2 emission scenarios that would lead to stabilization of the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere at 450, 550, 650, 750, and 1,000 ppmv. Source: adapted from Figure 6.1, 2001 IPCC synthesis report.

These emission scenarios all have a similar appearance, with emissions initially rising, then turning and declining sharply. The lower the CO2-stabilization target, the sooner this reversal occurs. Stabilizing at 550 ppmv, for example, requires emissions to peak at 11 GtC around 2035, then decline to 7 GtC by 2100 and 3-4 GtC by 2200. Stabilizing at 1,000 ppmv, on the other hand, allows emissions to grow until nearly 2100, with a slow decline over the following two centuries.

The scenarios in the figure are not the only way to reach a specified CO2 stabilization target. There are many paths to reach each target, including some that start cutting emissions immediately and others that make larger cuts starting later. But the shape of the scenarios, in which early emission growth is followed by sharp reductions later, makes the cost of attaining the concentration targets low. There are four reasons this shape tends to reduce costs: it avoids premature scrapping of long-lived capital equipment such as power stations; it allows more time to develop new low-emitting technologies; it allows time for the natural carbon cycle to help remove early emissions from the atmosphere by the time the concentration target becomes binding; and by delaying emission-reduction expenditures, it reduces their present value through discounting.

The lack of a long-term goal is one of the main failings of the Kyoto Protocol. The KP defined limits for emissions averaged over 2008-2012, and left completely undefined what the next step should be. This omission has become one of the major contributors to the present stalemate we are now experiencing in negotiations for the KP follow-on. A long-term goal gives stability and context to the overall planning environment that is missing from today’s debate.

2. Short-term actions. A successful emissions reduction program must do two things: a) motivate private-sector actors to invest money to develop the technology that will be required, and b) motivate the private sector to adopt that technology.

Putting a price on greenhouse-gas emissions does both things. By putting a price on emissions, companies know that research into new technology to reduce emissions will pay off because a market for the technology will exist.

Pricing emissions could be done through either a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system. The price could be low at first, but it must rise over time following a pre-announced schedule. And the private sector must be convinced that the politicians have the backbone to stick to this schedule.

3. A political strategy. This is the most difficult part of designing an effective policy. What countries make the first cuts? How then does the regime expand to include all countries? For both practical and philosophical reasons, countries like China and India are unlikely to agree to participate in the first stage of any GHG reduction regime. On the other hand, these countries must eventually be brought into the regime. And given the rate of growth of emissions from China and India, they must be brought in as soon as possible.

4. Adjusting policies over time. There must be a procedure for reassessing and adjusting efforts over time. Although emissions reductions must begin despite present uncertainty, the presence of uncertainty means that policies cannot be established once and for all. In particular, the form and stringency of policies, the mix of technologies being developed and adopted, and even the long-term goal for climate stabilization will all have to be repeatedly reassessed and potentially revised over the many decades it will take to stabilize the climate. A similar process has been used to great effect in the Montreal Protocol.

The most serious challenge for such a process will be balancing the need for policies to respond flexibly to new knowledge and capability with the need for a stable and credible policy trajectory to allow orderly investment and planning.

5. Adaptation. People, organizations, and communities will adapt to changing climate conditions on their own, but government policy can also aid adaptation in several ways. Governments might undertake specific adaptation measures by spending public money — to build seawalls, for example. Or they might require adaptation measures by private citizens, such as changing zoning codes to restrict building in coastal areas, flood plains, or other vulnerable areas.

Of particular importance is the role of information — climate predictions, impact studies, information about potential responses, or technical assistance — in promoting adaptation. Such information can help people shift from reacting to climate change that has already occurred toward anticipating future changes.

Adapting to anticipated climate changes tends to be more effective and less costly, particularly for planning and investment decisions with time horizons of decades or longer. Improved climate analysis and projections can also reduce the risk of private actors mistaking short or medium-term climate variability for a longer-term trend.

Many potentially valuable adaptation measures will not be specific to climate, but rather will reduce the general vulnerability of people and society to many kinds of risks. For example, strengthening public-health infrastructure will help reduce health risks from climate change, but will also provide enhanced capacity to respond to other health threats. Strengthening emergency-response systems and implementing policies to promote development and poverty reduction would similarly help to reduce vulnerability both to climate change and to other threats.