Time to clean house: The FDA’s photos of the conditions at Wright County Egg, shown at the hearing, include piles of decomposing chickens at the back of the hen houses. Factory farms have a high rate of mortality, but they’re supposed to clean up after themselves better than this.Photo: FDA

Time to clean house: The FDA’s photos of the conditions at Wright County Egg, shown at the hearing, include piles of decomposing chickens at the back of the hen houses. Factory farms have a high rate of mortality, but they’re supposed to clean up after themselves better than this.Photo: FDA

Wednesday’s House Energy and Commerce Committee’s hearing on the egg recall brimmed with interesting information on the two interlocking companies — Wright County Egg and Hillandale Farms — that sent out 550 million potentially salmonella-tainted eggs and sickened at least 1,700 people. For a conventional account of what went on at the hearing, check out this The New York Times report. It has the goods on “habitual violator” Jack DeCoster’s public apology, as well as the sparks that flew as Congress members did their posturing and grandstanding.

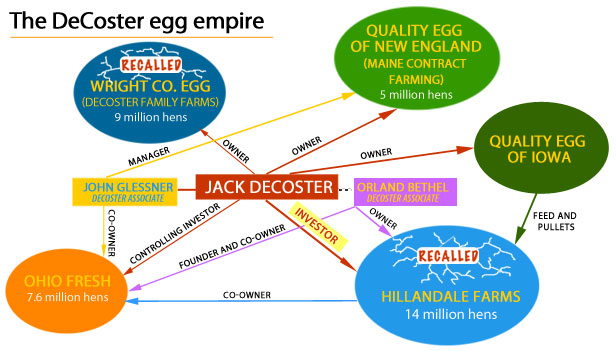

I’m more interested in the subtle details that emerged. For students of the food industry and the corporate machinations behind the recall, the day’s events were nothing short of riveting. In two earlier posts — here and here — I established that Jack DeCoster stands at the top of a sprawling empire of companies that, combined, sell more eggs than any other. The key piece of the puzzle has been establishing links between DeCoster’s Wright County Egg and Hillandale, on its own the nation’s third-largest producer. The following graphic might be helpful in keeping the ties straight.

Grist infographc

Grist infographc

The clueless CEO and the crafty capo

In what was probably the most memorable moment in Wednesday’s hearings, Orland Bethel, the elderly chief executive of Hillandale, tensely invoked his Fifth Amendment rights and refused to testify. I don’t believe I’ve ever witnessed someone “take the Fifth” outside of the movies or television. Drama!

I didn’t really understand Bethel’s move until I realized that the subcommittee had released two juicy emails between Bethel and John Glessner, Jack DeCoster’s longtime lieutenant and business collaborator. First, some quick background. Glessner and DeCoster are intimately linked. In this post, I showed that on at least three occasions — one in Iowa, one in Ohio, and the other in Maine — Glessner has acted as the public face of entities really owned by DeCoster. The two men have even, as I show in that post, been convicted of a crime together. As the Cleveland Plain-Dealer memorably put it, “In several court filings over the past decade, Glessner shows up as either DeCoster’s employee or as someone buying farms from him.”

In his emails to Glessner, Bethel seems desperately determined to dissociate his company from the toxic DeCoster name. The first email, dated Aug. 30, concerns Ohio Fresh Eggs, a company officially co-owned by Bethel and Glessner but in which DeCoster is known to be the chief investor.

“What is the status of Ohio Fresh Eggs and DeCoster,” Bethel opens his email, raising a question that many of us have been asking. Whatever the status is, Bethel makes clear, he wants DeCoster to vanish:

Unfortunately Hillandale Farms can have absolutely no association with Jack, anywhere. We will move in another direction in Ohio if we can not get it officialy [sic] done. We have to be able to say how it is with no half truths. I will be happy to try and help make it happen.

The “no half truths” bit is interesting, suggesting that Bethel assumes Glessner might be familiar with deceit as a business strategy.

Then Bethel writes something that strikes me as downright poignant: “It seems that if was Glessner and Hillandale that we could tell the world our customer base would embrace us.”

OK, so there are grammatical issues with that sentence that would make any editor wince, but the way I read it, Bethel is saying that if they can show the world that Ohio Fresh Egg is owned by Hillandale and Glessner, with no association to DeCoster, than the company can thrive unaffected by the recall and by DeCoster’s growing infamy. The poignant part is that Bethel seems to be disregarding that Glessner himself carries the full taint of DeCoster: he is clearly DeCoster’s longtime fixer and front man. Bethel is behaving like a politician trying to publicly distance himself from a mafia boss while also embracing the boss’ consigliere.

Bethel then turns his attention to events in Iowa, site of the hen facilities that produced the recalled eggs: “WE [sic] are not sure how we want to proceed in Iowa as we have been told by Costo [sic] and Wal Mart that they will not be doing any business if Jack and his people have any involvement in management or ownership.” Again sounding like a figurehead exec asking an underling for key information about his company, Bethel ends the email like this: “What is the latest in Iowa? Give me the good and the bad.”

In the second email, dated Aug. 31, Bethel ramps up the urgency as the FDA’s investigation of Hillandale’s Iowa operations gets more intense. The FDA has hit his Iowa offices with a search warrant, Bethel reports, and part of what they’re investigating is “corporate structures and records.” Sounds like the FDA, too, wants to know more about precisely who owns what in the DeCoster/Hillandale empire.

Again, Bethel expresses determination to distance himself from DeCoster; and again, he finds it necessary to reject deceit as a business strategy:

Hillandale needs to totally disassociate itself from Jack and it has to be real. Hillandale has a good business base but it will all be gone if I don’t move quickly and i won’t try to deceive the public.

Bethel alludes approvingly to an “outline” that Glessner has concocted, evidently a plan for proceeding in the wake of the recall. “I need to talk directly with you to explore what you have in mind and see if we are on the same page,” he writes.

To me, the fascinating thing about the emails is that Glessner, DeCoster’s fixer, emerges as Bethel’s go-to guy for both strategy and action. And Bethel clings to the notion that he can cut ties to DeCoster while remaining close to Glessner. It’s all very bizarre.

Feed milling about

The other big bombshells came from Peter DeCoster, who testified alongside his father. In his opening statement — which he read more or less verbatim from a previously released prepared speech (text here) — the younger DeCoster declared that “in May of this year, FDA inspected our feed mill. No deficiencies were cited.” Hmmm. There had been no other reports of such an inspection previously.

The claim is significant, because investigators are zeroing in on the DeCosters

‘ feed mill as the probable source of the outbreak. Recall that in its post-outbreak inspection, the FDA found deplorable conditions in the feed mill: signs that wild birds were feasting on feed and holes throughout the storage system large enough for rodents to crawl through. The storage area for bone meal, a component in industrial hen feed, was particularly dodgy: “Feed grain level sensor leading into ingredient storage bin 7, containing meat and bone meal, was off to the side with approximately a 2-inch gap. Avian-like feces were observed on top of this feed sensor.”

So FDA inspectors showed up to the same place in May and everything was fine? Peter DeCoster made that claim under oath. According to Des Moines-Register correspondent Phil Brasher, who attended the hearing, FDA deputy commissioner Joshua Sharfstein later flatly denied that the FDA had inspected the facility in May. (An FDA press officer is looking into the claim for me. Check back later for updates.)

Peter DeCoster made another claim under oath that the FDA’s Sharfstein later challenged, Brasher reports. In his testimony, Peter DeCoster strongly suggested that the salmonella outbreak stemmed from the bone meal that Wright County Egg had purchased and mixed into feed. In other words, the whole thing came from the outside!

Not so fast, counters Brasher:

Joshua Sharfstein, the FDA’s principal deputy commissioner, told reporters after the hearing that there was widespread salmonella contamination on the farm and that there was no reason to believe that the feed ingredient, meat and bone meal, was the source of the bacteria.

“The FDA has not reached that conclusion at all,” he said. Because of a lack of prevention measures, the farms were spreading the bacteria rather than catching and eliminating the contamination, he said.

From Bethel’s emails to Glessner, it sounds like the corporate offices are in as much disarray as the hen houses and the feed mill.