Photo: Mark Kjerland & super.heavy via flickrTalk with healthy-food advocates in urban centers across the country, and frequently, you’ll hear the same story. It goes something like this:

Photo: Mark Kjerland & super.heavy via flickrTalk with healthy-food advocates in urban centers across the country, and frequently, you’ll hear the same story. It goes something like this:

Once upon a time, this city was full of grocery stores. Then came urban renewal/an economic downturn/a mass exodus of the wealthy and, one by one, the groceries closed up and moved to the outskirts of the city. Since then, there have been Safeways/Krogers/Publix that have set up shop here and there, but they all end up leaving. Now we have 100 liquor stores for 25,000 people in this part of town, and the closest these stores come to selling fruit is the Arbor Mists in the drink cooler.

Thus, the United States has ended up with so-called “food deserts,” low-income enclaves that lack easy access to grocery stores selling healthy food and fresh produce.

It’s not only the biggest cities that have lost their grocery stores. While it’s hard to find a good grocer in parts of Atlanta and New York City, fresh veggies can be equally difficult to come by in places like Durham, N.C.; Tucson, Ariz.; and Nashville, Tenn.

According to Miriam Liebovitz of Community Food Advocates, a Nashville organization working to increase access to healthy food, carless residents of South Nashville must frequently take multiple buses and spend hours in transit to the nearest supermarket. “We’re working on getting policy incentives, tax and building incentives, to try and get grocery stores into Nashville neighborhoods,” she says.

Marketing justice

The work done by organizations like Community Food Advocates falls under the phrase du jour “food justice,” a term that’s all about equity, says Oran Hesterman, an agronomist and food systems expert who now heads up Detroit’s Fair Food Network. Those working for food justice believe people should have equitable access to healthy food, equitable opportunities to produce such food, and equitable chances to find living-wage jobs in the food and agriculture system.

Hesterman, like others in the food-justice field, see problems like skyrocketing obesity rates and diabetes as symptoms of a broken food system in need of extensive rebuilding. Their research shows that “the symptoms of that broken system show up in our low-income communities quicker and more harshly,” he says.

Alison Alkon, a sociologist at California’s University of the Pacific who studies the food-justice movement, likens it to the fight for environmental justice that sprung to life in the 1970s, when low-income communities and communities of color realized they were being hit with a double environmental whammy — extra exposure to toxic operations on the one side, and lower access to environmental amenities like parks and clean air on the other.

These residents also say they want what most people already have easy access to — a full-service grocery store in their neighborhood that would offer a wide range of products for one-stop shopping.

But like environmental justice issues, the causes and impacts of lack of access to food frequently have multiple historic causes, ranging from structural racism to poor urban planning.

“Planners did not actively try to make neighborhoods underserved … but by certain planning decisions, the end result was the same,” says Samina Raja, a planner at the University at Buffalo.

Due to a push from activists and local communities, planners are starting to include food access in how they manage city planning, but there’s a ways to go, says Raja. “Not having paid attention to food for several decades, we’re in a pretty dire situation in terms of disparities and justice.”

As the country’s obesity epidemic looms large and Michelle Obama continues to push healthy food initiatives, numerous cities have started to think about how lack of access to healthy food can affect the health of their residents, and thus reduce the amount of money they spend on healthcare for diet-related problems.

“Ultimately, it’s the best preventative medicine we have — eating healthy,” suggests Hesterman, pointing to efforts like Pennsylvania’s Fresh Food Financing Initiative, which provides incentives for grocery stores to open in underserved, low-income areas, as a model cities around the country are looking to follow.

Declaration of independents

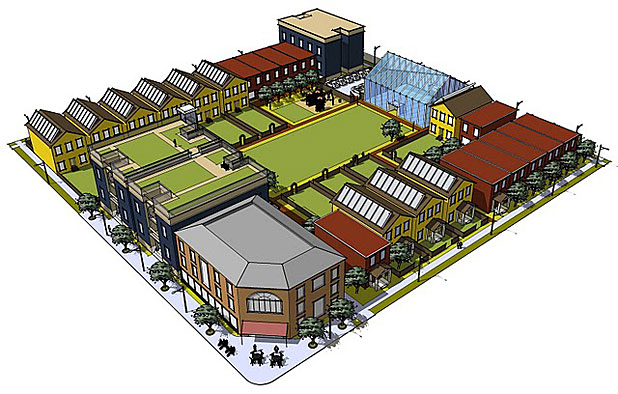

Building grocery stores in an underserved area is one concrete step toward making access to food more equitable, but it’s neither a simple task nor a straightforward solution.

As with many young social movements, there is tension between what the activists — who often come from outside the impacted communities — seek, and what those experiencing the problem view as the cure.

Activists often push to create (frequently small) independent grocery stores, cooperatively- and community-owned, or to get fresh produce in existing corner stores through programs such as Healthy in a Hurry in Louisville, Ky., and the Healthy Bodegas Initiative in New York City.

Research and focus groups completed by Hesterman’s Fair Food Network, the Oakland research group PolicyLink, and academics like sociologist Alkon, however, show that many residents of low-income neighborhoods do not yet use the alternative venues offered by food justice groups. These residents also say they want what most people already have easy access to — a full-service grocery store in their neighborhood that would offer a wide range of products for one-stop shopping.

West Oakland, Calif., is one of the few communities to have successfully created a small-scale cooperative grocery stores. Thus far, it’s received a positive response from the community, says James Berk, one of seven worker-owners at Mandela Foods Cooperative. The marketplace, located across the street from a major public transportation hub, stocks fresh and organic produce and offers classes on cooking and nutrition.

This video from PolicyLink celebrates Mandela’s first year in operation:

As you can see, Mandela looks very different from a standard grocery store, with bulk bins selling organic beans, grains, and dry goods taking up prime real estate in the space. At 2,500 square feet, it’s about the size of a corner store, although it takes a strong stance against selling liquor.

“The closest thing that we come to alcoholic beverages is kombucha [a fermented tea],” says Berk.

Berk, a West Oakland resident, speaks from personal experience when he dismisses chains such as Safeway in favor of cooperatively- and community-owned stores like Mandela: “They’re just out there to make their buck. There’s no interest, and they can just pack their bag up and leave. There have been grocery stores here in the past, but they don’t last long.”

While stores like Mandela may be in for the long haul, they still have some growing to do. Its vegetables might be fresh and its employees friendly, but Mandela does not yet sell household goods like toilet paper and cleaning products, and has received mixed reviews by local news outlets for its lack of visibility to the community it is working to serve.

People’s Grocery, another Oakland food justice group, was once known for its mobile produce truck that sold fresh food to West Oakland residents. It’s since left the grocery business to focus on nutrition education classes, an affordable “veggie box” service, and a food industry job training program, according to Victoria Fabella, operations manager for the nonprofit. The organization sees this education and training work as building the foundation for a better food system in West Oakland, she says.

Brahm Ahmadi, a co-founder of People’s Grocery and one of the brains behind the produce truck, is now raising funding for a West Oakland grocery store that would, in a model similar to Mandela’s, serve low-income West Oakland residents. Hank Herrera, who once led Oakland’s HOPE Collaborative, a WK Kellogg Foundation-funded community food project, has also started a for-profit company working to build grocery stores around the city’s underserved areas.

Similarly, the Chicago-based Fresh Family Foods, a project of food justice activist LaDonna Redmond, aims to be a community wellness center, offering nutrition workshops to local residents while also selling healthy food. Like Mandela, Fresh Family Foods differs significantly from mainstream grocery stores in its offerings and operating hours. And like many food justice cooperatives and alternative food provisioning models, it’s been a long, slow slog for the store to get up and running, mostly because of difficulties in raising money, says Redmond.

“You can’t get enough capital to actually open the store, and if you are lucky enough to get someone to open the store, you have to get enough volume for the equation to work for you. You have to purchase food at an affordable price so you can sell it to people at an affordable price. And a single store isn’t able to be competitive because you can’t get the volume,” she explains.

Redmond ran her project, formerly known as Graffiti and Grub, as a produce market with limited hours last year. She opened full time in August, and managed to do this by spreading out the risk and expense involved in starting a store. Redmond teamed up with a Chicago restaurateur and community businesswoman to open the 3,000-square-foot shop, which not only offers staples, fresh produce and meat, but also sells several local African-American producers’ wares, including bakery goods, specialty popcorn, and prepared meals.

Watch video of the newly opened store:

Release the chains

Chain grocers, although perceived as more convenient by residents, come with their own well-chronicled issues, such as displacement of local businesses and creation of primarily low-wage jobs.

Chicago, home base of both the Obamas and Redmond’s small-scale food project, has recently approved Walmart’s expansion into low-income, underserved areas in the city’s South side. Walmart and the city tout this move as directly following Michelle Obama’s push to eliminate food deserts, part of the Let’s Move anti-obesity campaign. Obama’s campaign has been supported by the Department of Agriculture, which is providing $400 million this year to bring grocery stores into underserved areas.

When the grocery store that comes in is Walmart, however, food justice advocates have a hard time celebrating, says sociologist Alkon.

“Michelle Obama and her Healthy Kids campaign is in the process of making all this public money available for large chain grocery stores to go in inner-city neighborhoods, and, for example, Walmart is really excited about it.” says Alkon. “And food justice activists are kind of like, hey, wait a minute, we helped make this problem well known, but the solution is really different from what we envisioned.”

Hesterman, of the Fair Food Network, says at this stage in the game he appreciates experimentation to increase access at multiple levels. He points to Detroit’s “Double Up Food Bucks” program, which allows food stamp recipients to get a matching dollar for every food stamp dollar they spend at a farmers market, up to $20 per visit.

“The great thing about on-the-ground projects is that you can create living, breathing examples of how the system could work differently,” he says.

Hesterman hopes these smaller projects — popping up in places like Nashville, Oakland, Philadelphia, and Durham — will lay the groundwork for a broader movement politically and socially.

“We need to find ways to really connect a much broader population and much broader interest area to this issue,” he emphasizes.