For decades, the federal government has watched idly while a few gigantic companies grabbed ever-greater control of the food industry. As big players gobble smaller ones, they concentrate power at the top of the food chain — and apply relentless pressure to cut costs, giving rise to many of the things I hate about the food system. Workers, farmers, the environment, animals, public health — all get abused so that mega-retailers like Walmart, meat producers like Smithfield, and corn processors like Cargill can keep costs down while profitably selling cheap food.

Well, in a sharp break from its predecessors, the Obama Justice Department is actually acknowledging the problem and contemplating actually doing something about it. The DOJ has been holding public meetings to let players in the food system air out their views on the issue.

I will be very surprised — and very pleasantly so — if anything substantial comes of the exercise. But it’s fascinating to watch it play out.

Over on Eclectic Edibles, blogger Shwankie found an interesting tidbit while watching the C-Span feed of recent hearings in D.C. Apparently, a representative from the Food Marketing Institute got to mouthing the food industry’s main defense of consolidation: that it benefits U.S. consumers by allowing us to spend less on food as a percentage of income than the citizens of any other country in the world.

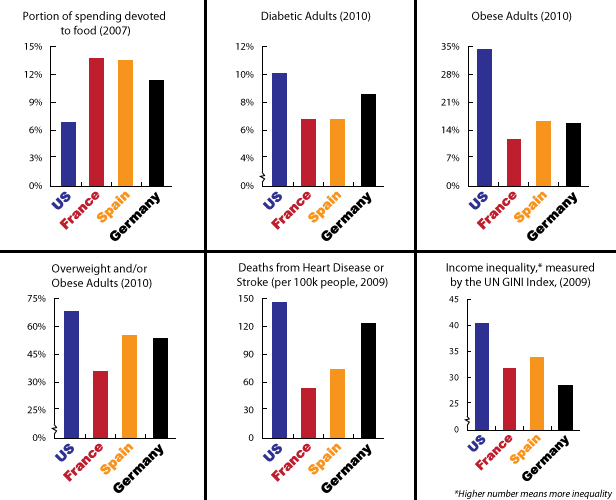

Comparing U.S. consumers’ food expenditures to those of the French and Spanish, the flack concluded that our tightly consolidated food industry is serving us a higher “quality of life” along with all the burgers and frozen dinners.

Shwankie very smartly shredded that assertion by coming up with a little chart comparing food expenditures and various diet-related troubles among the United States, France, and Spain. She didn’t give her data sources, so I felt uncomfortable reprinting her chart. Inspired by her, I came up with my own version. I threw Germany into the mix, just to broaden the sample.

Pay now or pay later: Americans’ and Europeans’ consumption habits reveal different priorities — and those incur different penalties. Spending metric reates to food consumed at home. Sources: USDA and OECD

Pay now or pay later: Americans’ and Europeans’ consumption habits reveal different priorities — and those incur different penalties. Spending metric reates to food consumed at home. Sources: USDA and OECD

Now, correlation does not prove causation. But if the food industry wants to claim that its abundance of cheap crap delivers higher quality of life, it will have to explain why our citizens come down with diet-related maladies at rates so much higher than those in countries where food is pricier. For most of us, “quality of life” does not dovetail with gaining too much weight, getting diabetes, and dying of a heart attack.

I added to my chart a metric not found in Shwankie’s post: the United Nations’ “Gini index” of income inequality. That’s my tribute to U.K. researchers Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, whose book The Spirit Level: Why Equality Makes Societies Stronger has been blowing my mind.

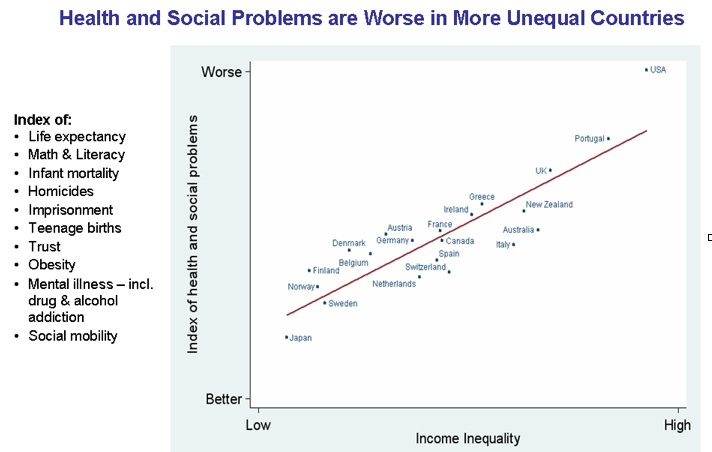

If the food-industry rep is probably dead wrong that cheap food increases quality of life, Wilkinson and Pickett point to a factor that actually seems to: income equality. Below, find their chart tracking income equality against a broad quality-of-life index.

From The Spirit Level slides, made available by The Equality Trust.

From The Spirit Level slides, made available by The Equality Trust.

To me, cheap food underpins our highly inequitable income system. If we’re going to have a large low-income class, a perpetually squeezed middle class, and a small caste of super-rich, then a cheap food system plays a vital role in keeping those at the bottom fed — if under-nourished.

Wilkinson and Pickett’s inequality work has provided me with a new way of looking at food-system reform. It may be that that a food system predicated on slashing costs — at the expense of the environment, workers, animals, and public health — is a symptom of a broader problem: an economic system that concentrates power and income at the top. It may well be that we can’t really reform the food system until we reform the economy. That’s an idea I’ll be mulling and teasing out in the new year.