Central Valley almond trees reflected in flooded irrigation water.

Central Valley almond trees reflected in flooded irrigation water.

To many people — particularly environmentalists and family-farm aficionados — the Westlands Water District, on the dusty west side of California’s San Joaquin Valley, conjures up an image of a sprawling empire of large-scale agribusiness. Roughly 600 farmers own land within the district, and grow a veritable cornucopia of tomatoes, almonds, pistachios, lettuce, cantaloupes, grapes, and other crops.

Many farms here are huge, to be sure: One family farms at least 25,000 acres. But there are plenty of smaller farmers like 42-year-old Shawn Coburn, who grows 1,200 acres of mostly almonds. And to him, Westlands is an American Eden.

“There’s a long list of haters,” says Coburn. But “we have the best dirt out there. It’s the best ground in the world.”

There’s only one problem. While the soil here may be good, there’s not much water. At least not since 2007, when a federal judge drastically cut back farmers’ water supplies to protect endangered fish in the Sacramento and San Joaquin river delta in the geographic heart of the state. A three-year drought began clobbering California that same year, making life even tougher for farmers like Coburn.

In 2009, farmers in Westlands had their annual water supply rationed to just 10 percent of what they’re entitled to under their contracts with the federal government. (More about that later.) Here and in neighboring irrigation districts, farmers were forced to idle, or “fallow,” about a quarter-million acres of cropland because of drought and pumping restrictions, which cost them somewhere around $350 million in losses.

Farms in Westlands make up a little less than one-tenth of the roughly 6.9 million acres of farmland in California, and other parts of the state are facing their own water crunch. But paradoxically, no one has been hit harder than the farmers here. Despite being widely viewed as one of the most powerful participants in California water politics, Westland’s contracts for water from the federal government are some of the most vulnerable to being shorted, thanks to the arcane hierarchy by which water is apportioned during dry times.

The water shortage is unquestionably taking its toll. “It’s changing the landscape,” says Coburn. What’s happening here is providing a sneak peek at the problems that farmers not only in California, but all over this drying world, will soon confront. Farmers are shifting to higher dollar-value crops that will cover the water price hikes — but, paradoxically, are more sensitive to drought. They’re pumping groundwater as an emergency supply of water — and burning through that safety net even as it saves them from the current dry spell. And some farmers here are beginning to think about an exit strategy from agriculture altogether.

Water shipment down

On a farm, nothing happens without water. And in California’s Central Valley, which includes the Sacramento Valley to the north and the San Joaquin Valley to the south, virtually all of the farmed acreage is irrigated. Irrigation districts like Westlands are local-government entities that hold long-term contracts for water supplied by two massive water projects: the Central Valley Project, which is operated by the federal government, and the State Water Project. The districts, in turn, sell water to individual farmers within their boundaries.

Yet as demand for water has grown throughout the state, as efforts to protect endangered species have increased, and as drought has darkened the water forecast — a problem that’s likely to become more frequent with climate change — irrigation districts, particularly those on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley, have found themselves increasingly unable to supply farmers with water. Even though Westlands, for instance, holds water contracts with the federal government, it signed those contracts relatively late, compared with other districts. As a result, when water supplies are tight, the government “shorts” Westlands’ contract to ensure that other irrigation districts with better contracts get their water.

That water crunch is spurring farmers to make a wide array of adaptive responses. Water rights are generally tied to specific pieces of land, but water can be moved — bought, sold, and swapped, just like stocks — to areas of greatest demand, and diverted to those who can pay the most for water. In drought years like 2009, farmers make extensive use of transfers to cover water-supply reductions. But the less water is in supply, the dearer prices become.

Water shortages are also changing the menu of crops grown in California. Take the case of cotton, for instance. Cotton has long a favorite whipping boy of environmentalists and agricultural reformers because it is government subsidized and relatively thirsty. In 1979, California farmers grew about 1.6 million acres of the stuff. But over the past three decades, cotton has largely shuffled off the stage in California. In 2009, the state’s farmers grew only 191,000 acres.

When a farmer plants an almond tree, he’s practically handcuffed to that tree. He’s banking that, after the tree takes a couple years getting up to full steam, it will produce a crop for roughly the next quarter century.

Many farmers say that one of the primary factors behind that decline, in recent years especially, has been water scarcity, which has driven up prices for water. Cotton has never had spectacular margins, so farmers are always vulnerable to big increases in the price of the “inputs” it takes to grow the crop. And, in the face of the water cutoffs, Westlands farmers have had to pay as much as four times what they normally do for water.

“That’s what drove cotton out of the west side,” says Marvin Meyers, a longtime Westlands farmer who now grows mostly almonds and olives. Farmers who use the water to grow higher-value crops like almonds “can afford to pay more,” Meyers says, “because the almond returns are greater than you would have gotten for cotton.”

Watering the desert: Irrigation in the Coachella Valley.Photo: AquaforniaIndeed, since roughly the mid-1980s, California’s agricultural landscape has shifted from low-value commodity crops to ones that make more money for farmers: not just almonds, but wine grapes, pistachios, walnuts, and pomegranates. As cotton acreage has decreased, almond acreage has been steadily growing. In fact, it has roughly doubled since 1986, to around 800,000 acres. (No other state in the U.S. grows almonds on a commercial scale; and, in fact, 90 percent of the world’s supply is grown here.)

Watering the desert: Irrigation in the Coachella Valley.Photo: AquaforniaIndeed, since roughly the mid-1980s, California’s agricultural landscape has shifted from low-value commodity crops to ones that make more money for farmers: not just almonds, but wine grapes, pistachios, walnuts, and pomegranates. As cotton acreage has decreased, almond acreage has been steadily growing. In fact, it has roughly doubled since 1986, to around 800,000 acres. (No other state in the U.S. grows almonds on a commercial scale; and, in fact, 90 percent of the world’s supply is grown here.)

A shift to better-paying crops, along with higher water prices, has also created the incentive for farmers to invest in water-efficient technologies like drip irrigation. In Westlands today, more than half of the farmed acreage is now drip irrigated, and it’s not uncommon for growers who focus on permanent crops, like Coburn and Meyers, to have 100 percent of their farms under drip systems.

Ironically, though, such moves haven’t relieved overall water stress. While farmers have become more efficient, they’re not using any less water. In fact, an acre of almonds in Westlands actually uses as much as 40 percent more water than cotton.

The giving trees

Farmers don’t talk much about the fact that

a water shortage is forcing them to grow crops that are actually more water intensive. But they are more candid about another twist in the hard new reality of water scarcity.

“Field crops” like tomatoes, lettuce, and melons give a farmer a little flexibility when a bad drought comes calling. If things get really bad, he can simply let the crop go for the year — leave it unwatered, try to ride out the year, and give it another shot the next year.

But tree crops — permanent crops — are different. When a farmer plants an almond tree, he’s practically handcuffed to that tree. He’s banking that, after the tree takes a couple years getting up to full steam, it will produce a crop for roughly the next quarter century. Pomegranates are productive for 25 years or more, too. And grapevines produce for 45 years on average, but can keep going up to 100. With these plants, the farmer can’t let the tree or vine go unwatered for a single year, no matter how bad a drought might roll through. No water, and it dies — and with it goes the initial investment, plus the potential earnings over the rest of what otherwise would have been a fruitful life.

“It just raises the risk curve,” says Mark Borba, who farms about 10,000 acres for himself and others on the west side. “You have that year-to-year uncertainty of, ‘Will I be cut so severely in water allocation that my crop investment will actually die?'” he says. “It can all come crashing down in one year.”

This move toward higher-value permanent crops has created an inflexible, “hardened” demand for water by erasing many farmers’ ability to roll with nature’s hydrologic punches. And that, too, is reshaping the geography on the west side. “Some people who have planted permanent crops are going out and buying land with no intention of farming it, but just getting that water and using on their (existing) crops,” Borba says.

Other farmers have taken a different tack, partly to avoid being shackled to orchards or vineyards that they can’t afford to not water. Last year, the total value of almonds grown in Westlands was the highest of any crop grown in the district. But not far behind was tomatoes. California isn’t a big fresh-tomato state, like Florida. Instead, farmers typically grow under long-term contract for processors, which themselves contract to large companies like Campbell’s and Heinz. The margins on tomatoes aren’t as high as, say, almonds or grapes, but they’re better than cotton — and a multi-year contract gives growers a dependable income over the life of the deal.

At least it does as long as they can hold up their end of the bargain and keep delivering tomatoes to the processor. An acre of tomatoes uses about the same amount of water as an acre of cotton, so short water supplies make it difficult to meet the contracts. That has spurred some larger growers to rent ground with better water rights outside of Westlands and move part of their tomato crop there. Just as some farmers are transferring water from one piece of ground to another to cope with water shortages, others are transferring their crops to farmland with better water.

Groundwater hogs

Water may not be flowing for California farmers, but cash is — at least for now. “Most of the [crops] that we grow here in California are at record or near-record prices,” Borba says. That’s due in large part to the fact that the state has a huge export market, and the weak dollar has driven prices up.

That has tempered the economic losses that farmers have suffered, but it hasn’t solved the underlying lack of water, which affects farmers’ ability to get the financing they need. Banks have always assessed each farm’s vulnerability to drought when its owner applies for financing, although they are loath to say much about the process publicly.

“You can’t take a brush and paint the whole San Joaquin Valley with one color,” says Vernon Crowder, an agricultural economist with Rabobank, which has emerged as one of the largest lenders to farmers in the area. “Everybody’s water situation is unique.”

Bankers now scrutinize farmers’ water options much more closely, and some farmers say, have become much more cautious about the risk they’re willing to take on.

“Listen, any banker who stays in this ag thing ought to have their head examined,” Borba says, and laughs. “It’s like financing a riverboat gambler who tells you, ‘Just give me another $50,000 bucks.'”

The trump card for these gamblers is groundwater, which farmers can turn to when their irrigation districts can’t provide a full delivery — and which banks see as a crucial element of farmers’ contingency plans. But as Crowder says, “the groundwater isn’t going to last forever.”

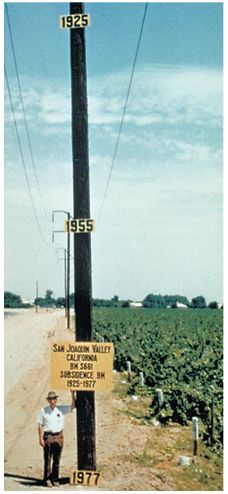

Not forever, and possibly not for much longer. A breathtaking groundwater “overdraft” has been run up in the Central Valley. So much water has been pumped out of the aquifers beneath the valley that the land over it is actually collapsing. An iconic photo taken in 1977 (left) shows a researcher standing next to a utility pole in Westlands; attached to the pole is a sign indicating the ground level in 1925, when pumping in the area began. It is roughly 30 feet over his head.

The current drought has only worsened that situation throughout the valley. A year ago, measurements beamed down by a pair of NASA satellites revealed that farmers in the Central Valley had pumped out enough groundwater since October 2003 to fill Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the nation.

And regardless of the self-defeating logic of turning to groundwater, a new well can cost anywhere from a half-million dollars to a million per pop. Many farmers — and smaller ones, in particular — simply can’t afford to make those kinds of investments to keep their farms going.

“You hear in the news about all these short sales, and that homeowners are upside down,” Borba says. “Well, there’s a lot of this land out here that’s upside down.”

Growers are bracing for what they see as the inevitable shakeout driven by this most recent round of drought — and, potentially, the sort of consolidation that originally made Westlands’ name synonymous with large, corporate farms. Many smaller farmers recognize that the economic clout of their more well-heeled neighbors — and cities like Los Angeles — will prevail when water gets really tight. They are keeping a wary eye on the weather, and especially the La Niña pattern that is taking hold, which will likely bring drier weather this winter. If that happens, the water that is available will only get more expensive for those who need it — and more valuable, for those who have it.

And so, although they’re not always eager to say so, many smaller farmers are quietly working out a Plan B in the back of their minds. In late November, as Shawn Coburn drove to look at one of his almond orchards on the west side, he allowed himself a moment of candor.

“I just want to make sure I’ve got a good exit strategy, when I sell the little bit of water I’ve got left,” he said. “Then I can get the fuck out of here.”