When I visited Detroit in June, I expected to find a kind of post-apocalyptic metropolis — a crumbling, near-empty city plagued by crime, poverty, and despair. As expected, every neighborhood I visited did feature empty lots, abandoned factories, and crumbling buildings. I didn’t see a single full-service supermarket — the city doesn’t have one — but I saw dozens and dozens of liquor stores. Although the city’s economic and social problems are stark, as I covered in my Detroit overview for Feeding the City, what I found amid the post-industrial rubble was a veritable beehive of community organizing.

And in the fashion of a city truly after my own heart, food has emerged as the key motivating force of Detroiters’ efforts to re-imagine their town as a thriving, livable place. I was struck by the cooperation on display — the way new-wave restaurateurs, market farmers, food-justice activists, and nonprofit advocates work together toward the goal of a healthy, inclusive food system where a food desert once stood. And while plenty of work remains to be done before that vision can be achieved, my week in Detroit left me with little doubt that it would be.

Here are three representatives of the spirit driving the 21st-century version of the Motor City.

Chard bargain: The author picking up some locally grown produce on a recent visit to Detroit.

Chard bargain: The author picking up some locally grown produce on a recent visit to Detroit.

Grown in Detroit

Detroit-wide

On a hot Saturday in June, I toured Detroit’s bustling Eastern Market, a glorious relic from that pre-automobile age when cities commonly had a central food market. Most days of the week, Eastern Market functions as a wholesale market selling produce and meat sourced from all over the country. (Locavores shouldn’t scoff — it’s probably Detroit’s most robust source of fresh food.) But on Saturdays, most of Eastern Market becomes a real farmers market, featuring produce from Michigan’s rich agricultural land. When I visited a few months ago, there was a festive air under the soaring ceiling as I made my way past stands featuring gorgeous piles of cherries and other stone fruit, along with greens, cabbage, beets, and more.

The stand that caught my eye had a large sign proclaiming “Grown in Detroit,” over an array of delicious-looking produce. Grown in Detroit is a cooperative of the city’s 37 market gardens; it gathers their produce and sells it, providing a direct link between a public hungry for fresh produce and its budding crew of urban food producers.

Grown in Detroit grew out of the city’s Garden Resource Program, a joint project of several local non-profits including Greening of Detroit, which administers it. The Garden Resource Program provides seeds and compost to to Detroit’s 1,200 vegetable gardens (including the market gardens that sell through Grown in Detroit). Ashley Atkinson, 31, director of urban agriculture and project development for Greening of Detroit, told me that Grown in Detroit started when several gardeners in the Garden Resource Program network decided they were growing “a ton of food and were ready to sell it.” Rather than each producer attempting to launch and maintain a farmers market stand, with all the logistical headaches and expense of moving food around the city and keeping it fresh, they decided to form a cooperative that would bundle all the produce.

The program launched in 2006, with a modest $600 in sales, Atkinson told me. Today, it sells Detroit-grown goods at farmers markets across the city, as well as to restaurants. Sales reached $43,000 in 2009, and are projected to hit $60,000 this year. If urban agriculture is going to reach its economic potential, city growers will need to be able to market their produce efficiently. Grown in Detroit, a creative partnership between the city’s market gardeners and local non-profits, provides a model for doing just that.

Brother Nature Produce

Corktown, Detroit

Visit Brother Nature Produce during the summer, and you might think you’ve entered an idyllic rural vegetable farm. A dozen or so raised beds teem with vegetables in various stages of growth, surrounded by three hoop houses. Here and there in the surrounding area, you see stand-alone houses; but most of what you see in the distance is open fields and a smattering of trees.

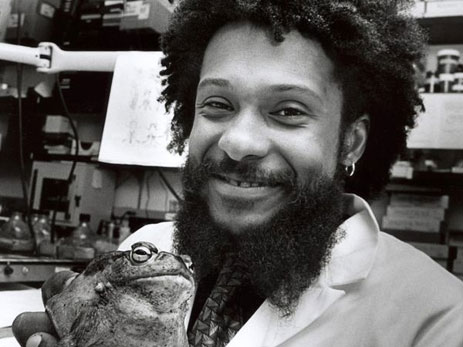

Bro in chief: Greg Willerer of Brother Nature Farm.(Tom Philpott)You’d never know it, but Brother Nature is plunked down right in the middle of Corktown, Detroit’s oldest neighborhood. “This used to be a densely populated area with a vibrant economy,” Brother Nature’s proprietor, Greg Willerer, explained to a tour of the farm I attended during the summer’s U.S. Social Forum. But Corktown, like the rest of the city, got caught up in brutal postwar economic decline (described in my recent essay); and was devastated by the Detroit Riots of 1967, during which dozens of the neighborhood’s houses burned down. According to Willerer, 85 percent of the original housing stock in his section of Corktown has vanished since the neighborhoods post-war heyday.

Bro in chief: Greg Willerer of Brother Nature Farm.(Tom Philpott)You’d never know it, but Brother Nature is plunked down right in the middle of Corktown, Detroit’s oldest neighborhood. “This used to be a densely populated area with a vibrant economy,” Brother Nature’s proprietor, Greg Willerer, explained to a tour of the farm I attended during the summer’s U.S. Social Forum. But Corktown, like the rest of the city, got caught up in brutal postwar economic decline (described in my recent essay); and was devastated by the Detroit Riots of 1967, during which dozens of the neighborhood’s houses burned down. According to Willerer, 85 percent of the original housing stock in his section of Corktown has vanished since the neighborhoods post-war heyday.

Amid such devastation, Willerer is rooting a business designed to sprout hope along with organic greens. Last year, he left a 15-year career as a middle-school teacher to devote his full attention to Brother Nature.

The two-acre farm surrounding his Corktown home started as a backyard gardening project six years ago. Focusing mainly on salad greens, Brother Nature operates two farmers market stands and sells to several Detroit restaurants. And in spring 2010, Brother Nature debuted Detroit’s first and only community-supported agriculture (CSA) program, with 25 members; it also rolled out an occasional “guerrilla cafe” that transforms the farm’s produce into street fare served from a vintage Airstream bus.

If it sounds like a lot of work, it is. At the U.S. Social Forum in June, Willerer addressed his 50 or so guests with the easy manner of a professional public-school teacher as well as the sleepy look of a farmer at the height of the growing season.

“The industrial food system has failed us here,” he said. “We have to figure out how to feed ourselves, and Brother Nature is part of that.” He told us that he saw Brother Nature as part of a broader movement to bring food justice to Detroit. He teased out a vision of a city full of small market gardens, providing both abundant food and space for kids to safely learn and play. He ended by drawing our attention to a bed of heirloom spinach that had gone to seed, its overgrown stalks bristling with seeds Willerer was planning to use for a future planting. He ripped off several long stalks and passed them through the crowd, urging us to take home seeds and plant them.

D-Town Farm

Rouge Park, Detroit Chairwoman extraordinaire: Marilyn Nefer Ra Barber, head of D-Town Farm.(Michael Hanson)In a corner of sprawling Rouge Park, the City of Detroit for decades ran a tree nursery, cultivating saplings that would grow into full glory along the city’s boulevards and in its parks. But the city’s post-’40s economic collapse forced a severe rollback of public services. A city that could barely keep its schools open could ill afford to run a tree nursery, so the Rouge Park facility lapsed into disuse by the 1980s.

Chairwoman extraordinaire: Marilyn Nefer Ra Barber, head of D-Town Farm.(Michael Hanson)In a corner of sprawling Rouge Park, the City of Detroit for decades ran a tree nursery, cultivating saplings that would grow into full glory along the city’s boulevards and in its parks. But the city’s post-’40s economic collapse forced a severe rollback of public services. A city that could barely keep its schools open could ill afford to run a tree nursery, so the Rouge Park facility lapsed into disuse by the 1980s.

But now, the once-overgrown space is in bloom again. This year, after years of negotiations between the Black Food Security Network and the city, D-Town Farm has emerged on a two-acre corner of the old nursery. D-Town has a 10-year lease from the city and is in negotiation to add an adjacent five acres to the garden. If all goes well, the project could be a model for creative land reuse in a city with thousands of acres of vacant land.

I toured D-Town during my June trip to Detroit. Neat lines of giant trees, remnants of the nursery, marked out the borders of the space. Although planting only began in the spring, D-Town already had the bustling vibe of a start-up project. Hovering over raised beds bordered by scrap wood, volunteers tended crops ranging from lacinato kale to tomatoes. Bees buzzed merrily along through the flower buds, gathering pollen for D-Town’s two hives. In a corner shaded by those old nursery trees, logs were stacked in overlapping squares, ready any day now to sprout shiitake mushrooms. A greenhouse stood ready for winter production.

“D-Town is a community self-determination project,” Black Food Security Network director Malik Yakini told me. He sees it as a kind of laboratory for the potential for urban agriculture — a place where people can learn intensive organic gardening techniques and bring them back to their neighborhoods. “The purpose is to show how underused or un-utilized city land can be put to productive use, and to mobilize people to work on their own behalf,” Yakini said.

For Yakini, mobilization is key. “One of the challenges of organizing African-Americans for this work is that many of our people associate agriculture with enriching someone else … slavery and sharecropping enriched whites with our labor,” he said. “What we’re doing is reframing agriculture for African Americans as an act of self-determination and empowerment.”

And once a significant number of Detroit’s African-Americans, four-fifths of the city’s population, rallies around around the potential of urban agriculture, the city’s politicians will have little choice but to make food production a priority for the city’s massive vacant land base. Because if they don’t, “if people aren’t mobilized to work on their own behalf, the politicians will come in to do what they want to,” Yakini warned.