Watchdogs say the Nuclear Regulatory Commission compromised public safety with its decision late last month to grant long-term renewal of the operating licenses for the Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant in southern Maryland.

Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant.

Photo: Dan Hamilton.

With the decision, the plant, tucked on a rural peninsula along the shore of the Chesapeake Bay, became the first of the nation’s 103 commercial nuclear reactors to win a 20-year extension of its operating licenses. Environmentalists fear the NRC’s move could portend a new wave of nuclear plant license extensions around the country, giving the nuclear industry a big boost at a time when many think it should be going the way of the dinosaur. At least 27 more nuclear plants are likely to seek similar extensions by 2003.

Though Calvert Cliffs’ previous licenses for its two reactors extended through 2014 and 2016, the plant’s owner, Baltimore Gas and Electric (BGE), requested the early renewal so it could make long-term plans in the face of approaching utility deregulation. The extension will allow the reactors to keep operating until 2034 and 2036.

Public Citizen and the National Whistleblower Center, two Washington, D.C.-based watchdog groups, claim the NRC streamlined the renewal process in a way that prevented the public from adequately addressing questions about the plant’s safety. The National Whistleblower Center sued the NRC last year, arguing that the new fast-track approval system did not give the opposition enough time to build a case against relicensing.

“Since NRC rewrote the rules, they have basically obviated any public participation,” said James Riccio, senior analyst for Public Citizen. Some information relevant to the renewal process was not made available by the NRC until after public hearings, Riccio claims.

A federal appeals court ruled in favor of the National Whistleblower Center last November, finding that the NRC’s fast-track system moved too quickly, but in an unusual move, the court threw out that decision 11 days later and ordered another hearing. New arguments were heard early last month and the case is still pending. But the NRC didn’t wait around for the court to issue a final ruling before giving Calvert Cliffs the go-ahead.

NRC = No Regulatory Criteria?

Riccio said the NRC gave Calvert Cliffs a “rubber stamp,” despite safety concerns that critics raised during the renewal process. The Union of Concerned Scientists submitted testimony faulting the NRC’s environmental impact statement on the plant for giving only superficial consideration to the plant’s potential impact on people.

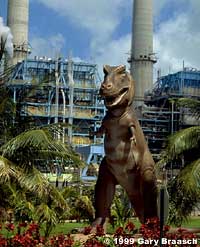

A T-rex at the Turkey Point Nuclear Power

Plant in Florida — which is the real dinosaur?

Opponents also lambasted the NRC for ignoring the environmental impact of nuclear waste that is piling up at Calvert Cliffs and other commercial reactors around the country. Calvert Cliffs plans to continue keeping its waste in above-ground dry storage in reinforced concrete buildings until the Department of Energy opens a national waste repository.

“NRC stands for No Regulatory Criteria that can significantly challenge this re-licensing effort,” said Paul Gunter of the Nuclear Information and Resource Service. The issue of waste was “Never Really Considered,” he said.

Riccio denounced the NRC’s relationship with the nuclear industry as parasitic. “They don’t want to take too big a bite for fear of killing their host,” he said. He suggested the same of Maryland’s Calvert County, whose economy has depended on the plant. “They need to figure out a way to wean themselves from the nuclear teat,” Riccio said.

Just One Big Nuclear Family

But many southern Maryland residents see no need to make that transition.

Calvert Cliffs, named for the steep walls along the bay’s shoreline, has been a landmark in the region since its construction began in 1968. Much as the plant’s generators, reactors, turbines, and transformers are literally carved into the Calvert Cliffs at the water’s edge, the plant itself has become thoroughly embedded in the county’s life.

Local business and community leaders largely welcomed the extension. “We’re thrilled,” said Linda Vassallo, Calvert County’s director of economic development.

“I think, in general, the plant and the employees who work there are considered a positive to the community,” said Calvert County Commissioner David Hale.

The plant is an economic behemoth in the region. BGE has a local workforce of approximately 1,300, making it the county’s largest single private employer. Its property constitutes about 30 percent of the county’s assessable tax base, according to Finance Director Terry Shannon. Last year, BGE’s property taxes contributed $21 million to county coffers, or about 18 percent of the total county budget, Shannon said. Calvert’s residents enjoy the lowest tax rate in the state.

When the NRC held a public hearing on the plant’s environmental impact in July of 1998, much of the testimony focused on the kind of green that doesn’t grow on trees. “When Calvert Cliffs located here, we went virtually overnight from one of the poorest counties in the state to one of the richest,” said former County Commissioner Mary Krug. The county is now the fastest growing in Maryland.

A Nice Neighbor?

Many community leaders also call BGE a good environmental citizen. The utility owns some 2,300 acres in the county but uses less than 300 for the nuclear plant. A portion of its property is dedicated to a nature preserve and trails, and old tobacco barns and the preserved foundations of an 18th century farmhouse dot the landscape. The company began working with the Nature Conservancy in 1992 to protect the Puritan tiger beetle, a threatened species that lives around the cliffs.

The power plant uses bay water as a coolant, taking in two and a half million gallons per minute and pumping it back out. Working under contract with BGE, scientists studied the effect of the plant’s discharge on water chemistry, shellfish, plankton, and other aquatic organisms in the Chesapeake, and found no ill effects.

A May 1999 NRC inspection team found “reasonable assurance that the effects of aging will be adequately managed” at the plant. And Calvert Cliffs supporters point out that the plant has a history of safe operation.

But Riccio of Public Citizen warned that a record of past safety doesn’t guarantee future safety. “It’s a psychological trap to believe that because something hasn’t happened, you’re doing just fine,” he said.