In the beginning of July, I arrived in New Orleans for an internship at the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. I met with Anne Rolfes, the coordinator and one of the founders of the nonprofit health and environmental-justice organization, and we discussed the work I would be doing. I was to organize a photo exhibit displaying images of Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath, taken by the residents of St. Bernard Parish.

For three weeks I worked with members of the community to create a collection of more than 300 photographs taken by 18 parish residents and four visiting photographers. The result was an exhibit dedicated to remembering what was lost and celebrating what has been recovered. “Life in the Wake of Katrina” is an attempt to bring the insider’s view to the outside and provide a deeper understanding of what happened to St. Bernard Parish, one of the worst-hit areas and the location of the million-gallon Murphy Oil spill. It is also for those who are in the process of healing — to show them they have not been forgotten.

Here’s what a few of them had to say.

Photos: David Taylor

Home: Before and After

My wife Suzanne and I lived in Meraux, La., part of St. Bernard Parish, just a few miles southeast of New Orleans. It was a Sunday and we were painting and doing other work we had started weeks before, when I passed the television while the latest weather report was playing. I told Suzanne the storm was heading our way and we needed to leave as soon as possible. We packed a couple changes of clothes, our pictures (which we had burned to CDs just a few days earlier), and our insurance policies. Just in case. Living in southeastern Louisiana we evacuate regularly, but up until this point we always returned a few days later to a normal life.

Nearly a month after Katrina, we were finally able to return. Words alone could not describe what we saw. The entire area looked as if a bomb had exploded. It was utter devastation. Seven months later, we were able to relocate to Tickfaw, La., which is about 60 miles northwest of New Orleans and out of future storm surge areas, we hope. It has been a year since Katrina and we are still struggling to get our lives back together, along with the rest of the Gulf Coast … It’s hard to imagine what it’s like to start over from nothing but we are doing it, one day at a time.

— David Taylor

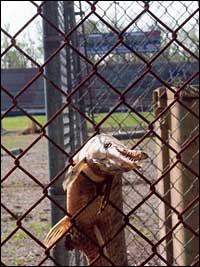

Photo: Marlene Himel

The St. Bernard High Gar

We were finally allowed back in the parish a month after Katrina hit. I drove around the school grounds and parking area of St. Bernard High School in Poydras, La., to see how my beloved school had fared. You see, I taught there for 20 years before retiring several years ago. I happened upon this poor alligator gar, stuck in the fence across from St. Bernard High football stadium. This innocent gar was truly a Katrina victim. I have an 8×10 copy of this shot in my living room in Slidell, La. I am living there while I rebuild my home in lower St. Bernard.

My home will be ready by December 2006. I am hopeful that within one to two years, St. Bernard High will again open its doors to a thriving community. I will surely present a copy of the gar photo to the new principal for display — the gar fish is shown fighting to get through that fence. The people of lower St. Bernard are fighters too — and we will be back.

— Marlene Himel

Matt

This picture was taken on Oct. 9, 2005, during the third of the many trips I have made to Chalmette, La., since the storm. The man in the photo is my nephew, Matt, standing in what used to be my parents’ living room. He drove down to Chalmette with my sister and me to help gut my parents’ house and recover any valuables we could find. My family moved to Chalmette in 1966, after Hurricane Betsy flooded our home in the Ninth Ward. I was seven years old at the time. Ironically, my parents chose to settle in Chalmette because it didn’t flood during Betsy.

Photo: Mary Beth Sessions

I have gone to see my parents’ house in Chalmette every time I’ve returned to visit and it’s still sitting there half gutted in pretty much the same shape we left it in last December. This is what’s left of the house I grew up in. Sometimes I will just stand there and stare, or I will rummage through the debris on the lawn or in the back yard hoping to find something important … There are so many items large and small just sitting out there in the sun that have memories attached to them, even though they are now completely unsalvageable. I hate to see them removed just the same because they represent my past and all the memories I have of growing up. Everything from furniture to old picture frames to my parents’ player piano (which they will never be able to replace since they’re on a fixed income), a faded poster from the 1984 World’s Fair, old tools, typewriters, radios, cameras, and record players, things made in the 1950s and 60s, woodwork sculptures that my dad has made by hand over the past 40 years, an old pot used for seafood boils since I was a child but now rusted beyond repair from the floodwaters. It’s all still there but completely ruined and unredeemable, the memories of my childhood just sitting there waiting for the bulldozer.

My parents are actually getting by quite well, given the situation. Their new neighborhood in Denham Springs [La.] is growing very rapidly, with most of the houses on the block still under construction, but I imagine that most of them have already been purchased with the new residents waiting to move in. My parents have discovered that several of their new neighbors are from Chalmette (surprise) and that a couple of them are former neighbors who moved away years ago but have now resettled in the same neighborhood.

— Mike Collins, photo by his sister

Katrina Takes Aim

I could smell the city before I ever saw the skyline. It was the worst scent I have ever experienced. Nothing could have prepared me for what I was about to encounter visually. As we neared our house, I couldn’t shake an overwhelmingly eerie sensation. There were no sounds, aside from the occasional military aircraft circling above us. The pesky Louisiana insects weren’t even buzzing.

Photo: Teri Stubbs

As I was about to walk onto the front porch, I stepped on something. A shudder went up my spine when I looked down to see that I was standing on the Aug. 28 edition of the New Orleans newspaper, The Times-Picayune. The front-page article was entitled, “Katrina Takes Aim.” We must have overlooked this edition of our daily news as we were under a mandatory evacuation on the morning the paper was delivered. The police were barking through bullhorns to evacuate immediately, as they should have. However, it made the chaotic time more unnerving.

While I must suspect that this issue made its way into my yard from a neighbor’s, I couldn’t get over the irony. While the entire contents of our home had been ruined and totally rearranged by the flooding waters that came subsequently after the levee breach, my newspaper lies outside my door as if the paperboy had just placed it there.

— Teri Stubbs

The Impossibly Precarious Balancing Truck

I arrived in St. Bernard Parish the day after the storm waters finally receded. What I remember most about that first moment is the hideous smell. I had never smelled such a putrid odor. I am told that rank smell was caused by odiferous bacteria that were released by the ubiquitous marsh mud. If I never smell that stench again, it will be too soon.

Photo: Randy Richards

I began taking pictures along Paris Road The corrugated metal buildings had suffered heavy damage, but I expected as much from non-brick construction. As I drove down Judge Perez Drive for the first time, I gasped. My mouth opened in awe and horror, and my hand instinctively moved to cover it. I stopped the van in the middle of the street and stepped out onto the highway. There was no traffic to worry about. In fact, there were no other vehicles at all. I was in the middle of what used to be one of the busiest locations in St. Bernard, in the center of a business-saturated thoroughfare of Chalmette, and there was nothing moving as far as the eye could see.

As I slowly turned to make a full circle, taking in the full picture of the blighted landscape, I wept. I had never seen firsthand destruction on this scale. I was overcome with emotions, partly because this is where I grew up. All the connections to my childhood were lying in ruins. There are no words that can sufficiently describe the complete widespread devastation I witnessed. And it wasn’t just the sights, as there were no sounds either.

There were no cars accelerating, no children playing, no air conditioners whirring, no birds chirping, and the loud staccato whine of the cicadas were completely absent. As I realized this, I also noticed there were no flies, ants, gnats, mosquitoes, or roaches. While that might sound like a good thing, it was kind of creepy at the time. The inrush of saltwater had chemically burned and killed the trees, grass, and other plants. All the people, plants, insects, and animals were either dead or gone — even the green anole lizards and flesh-colored geckos were absent. I was stunned. The only thing missing were the tumbleweeds of this abandoned desert-like ghost town.

Once I had recovered enough to remember why I came, I continued taking more pictures. The next photo I took was of a Rent-A-Center moving truck. It had come to rest in a position that can only be described as precarious and improbable. When the water receded, the truck’s wheel had come to rest, grill down, between several pipes and in just the right place to perfectly balance it. Its rear was sticking high in the air, suspended over the canal. It was not wedged — only gravity was holding it in place. It looked to me that if I touched it, it would fall, much like the balancing rocks of Arches National Park. Thankfully, Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner did not appear and knock it from its perch, so there it remained, mimicking a seemingly impossible high-wire act. I considered it a monument to the storm.

When I returned the following weekend to help my mom begin cleaning her destroyed home, the impossibly precarious balancing truck was gone. I presume it had been moved by officials fearing it would indeed fall and possibly hurt someone. A few weeks later I spoke with a St. Bernard Parish police officer who had seen the truck, albeit from the underside. As he and his partner passed under the bridge at dusk one evening, they wondered aloud what the heck it was. In the dim light, it looked ominous, hanging over them as they drifted beneath it. Until I told him what it was, he had no idea it was simply a rental truck. I suppose that’s the last thing anyone would guess would be resting on flimsy pipes high above their heads. It’s one of nature’s random and bizarre consequences, one of many I saw on my lonely tour.

— Randy Richards

A version of this article was originally published by the Community Arts Network.