This story was originally published by New Republic and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Everything is bigger in Texas, including the number of chemical plants, refineries, and other industrial facilities. So when one of the worst storms in American history hit the heart of Texas’ petrochemical industry, it also triggered one of the biggest mass shutdowns the area has even seen. At least 25 plants have either shut down or experienced production issues due to Hurricane Harvey’s unprecedented severe weather and flooding, according to industry publication ICIS. But those closures are not only disrupting markets; they’re also causing enormous releases of toxic pollutants that pose a threat to human health.

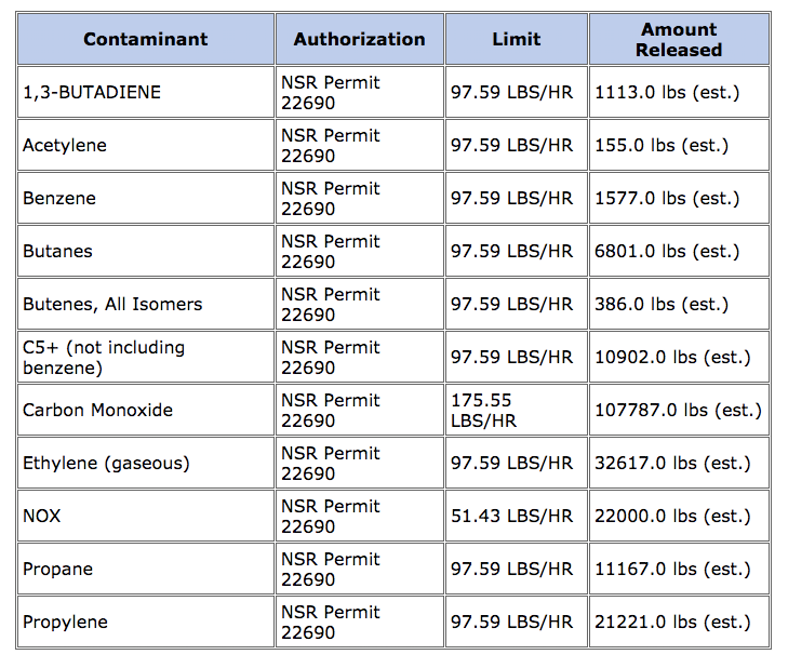

Take Chevron Phillips Chemical plant in Sweeny, Texas. When it shut down due to Hurricane Harvey, it released into the atmosphere more than 100,000 pounds of carbon monoxide; 22,000 pounds of nitrogen oxide, 32,000 pounds of ethylene, and 11,000 pounds of propane, according to a report the company submitted to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). A couple thousand pounds of 1,3-butadiene, benzene, and butane were released as well. All of these releases were far more than what was legally allowed.

Chevron reported similarly huge amounts of air pollution above legal limits due to the shutdown of its chemical plant in Cedar Bayou. 28,000 pounds of benzene, a known carcinogen. 56,000 pounds of nitrogen oxide gases, which react to form smog and acid rain. From just one “miscellaneous” source at the facility, a combined 40,000 pounds of various chemicals were released — and that source had no legal authority to release anything at all.

Smaller emissions events were also submitted to TCEQ. In preparation for Harvey, the Equistar plant in Corpus Christi released 5,000 pounds of both carbon monoxide and ethylene. The shutdown of Chevron’s Pasadena Plastics Complex caused some excess releases, mostly of carbon monoxide and isobutane. Javelina Gas Processing facility went far above its relatively low pollution limits for its shutdown, reporting releases of 10,000 pounds of carbon monoxide and 4,000 pounds of butanes, among other things. One Pasadena refinery released a bit of particulate matter.

Between Aug. 23 — the day it became clear Harvey would threaten Texas — and Aug. 29, industrial plants reported 74 excess air pollution release events to TCEQ, or nearly 60 percent more than the previous week. Those releases have so far totaled more than 1 million pounds of emissions above legal limits, according to Air Alliance Houston, an environmental nonprofit that crunched the numbers.

This chart shows excess air pollutant emissions from the Chevron Phillips Chemical plant in Sweeny, Texas, following Hurricane Harvey. TCEQ

The reason this is happening is simple: Petrochemical plant shutdowns are a major cause of abnormal emission events. The short-term impacts of these events can be “substantial,” according to a 2012 report from the Environmental Integrity Project, because “upsets or sudden shutdowns can release large plumes of sulfur dioxide or toxic chemicals in just a few hours, exposing downwind communities to peak levels of pollution that are much more likely to trigger asthma attacks and other respiratory systems.”

Air Alliance Houston’s Executive Director Bakeyah Nelson is concerned about how these shutdowns will affect nearby communities already suffering from Harvey. “The excess amount of air pollution puts communities in close proximity to these plants at risk, especially people with chronic health conditions,” she said. She also noted that communities closest to these sites in Houston — and in general — are disproportionately low-income and minority. Some residents have already been complaining of “unbearable” petrochemical-like smells.

But so far, TCEQ has not indicated these events have triggered health impacts. Its website offers no guidance for air pollution events from the storm, and TCEQ Media Relations Manager Andrea Miller told me the agency or local emergency officials would contact residents if an immediate health threat were to occur. What’s more, Miller said companies were probably reporting higher emissions that what actually occurred, “since underreporting can result in higher penalties.”

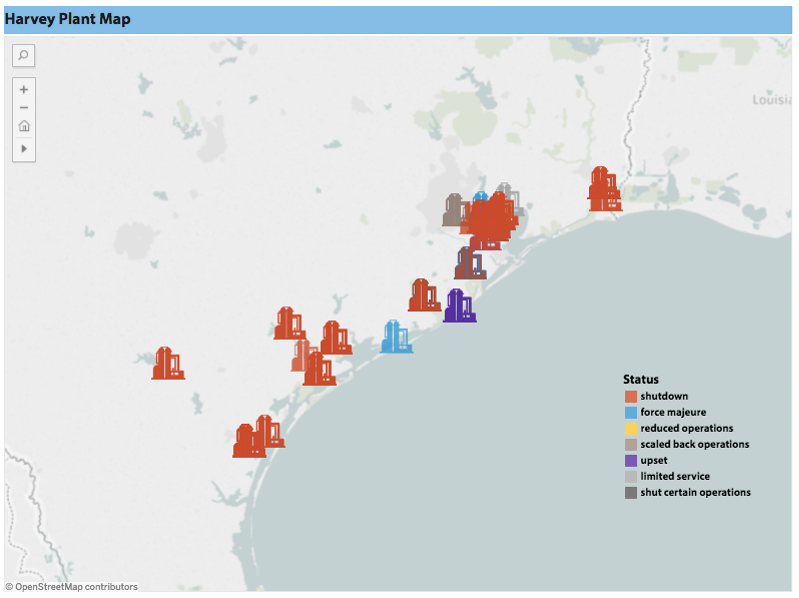

It’s unclear, however, how TCEQ would check many of the companies’ reports, since the agency turned off all its air quality monitors in the Houston area before Harvey hit. Miller confirmed as much on Monday, saying devices were either turned off or removed “to protect against damage or loss of these sensitive and expensive instruments.” Most of the plants impacted by Harvey are in the Houston area, as this ICIS map below shows.

A map of industrial facilities in Texas that have either closed, reduced operations, or otherwise scaled back because of Hurricane Harvey. ICIS

None of this is to say that companies could have done much of anything this week to stop the release of these chemicals. Indeed, there is no way to avoid large releases of air pollutants when refineries and chemical plants shut down, and there was no way these companies could have avoided shutting down their facilities faced with such a destructive storm. In their reports to TCEQ, companies generally say they are operating within safety and good air pollution control practices. And fortunately, as one meteorologist pointed out to me on Twitter, the continued rainfall in Texas is likely improving the situation, preventing pollutants from remaining stagnant in the air as it destroys everything else.

The real problem lies in the sheer number of facilities having to shut down or decrease operations at the exact same time — meaning they’ll also all eventually have to start back up. And emissions-wise, starting back up is just as bad as shutting down. That’s evident in the TCEQ emissions reports; rebooting the Formosa Plastics plant two hours outside Houston will be an enormous emissions event. In Corpus Christi, the Flint Hills Resources plant reported releases of 15,000 pounds of sulfur dioxide — a particularly harmful chemical — for its start-up. Most of this, too, is unavoidable, said Neil Carman, the clean air program director at Sierra Club’s Lone Star chapter. “Plants aren’t like cars or trucks where you just push a button and its starts,” he said. “These are huge refineries and petrochemical plants, so it takes a number of hours to heat up their units.”

When these plants restart, it’s less likely that the communities nearby will have the rain to save them. (And it seems a cruel irony to wish for rain that’s already caused so much damage.) But Nelson says the real problem is that the plants are allowed to operate so close to residential areas in the first place. Houston’s lack of zoning regulations have been front-and-center in discussions about why Harvey has been so terrible for the city, and that’s no different in the discussion about air pollution. “When the city gets back on its feet, it’s a good time to revisit the dialogue about where facilities are allowed to be located, and what precautionary measures can be taken in the future for communities in close proximity to these facilities,” Nelson said. Unfortunately, like so many other problems with Harvey, the discussion may come too late for the most vulnerable.