Today is National Agriculture Day. Have you hugged your farmer yet? To celebrate this special day, I’ve dug this column out of the archives, originally published three years ago this spring. It’s a tribute to mid-size farms, which don’t make nearly as much cash as their industrial-scale brethren and don’t get nearly the love lavished on small farms. I argue that reviving the health of mid-sized farms is a critical task if we’re going to create a just, fair, and green food system.

——–

Most people probably don’t think of Carrboro, North Carolina — a bustling town just outside of Chapel Hill — as a food lover’s paradise. But walk into the town’s beloved farmers market on a spring Saturday morning, and you see an impressive bounty on display.

Cash for comestibles in Carrboro.

Right now, it’s still greens season. Table after table bursts with bright stacks of collards, kale, and all manner of mustards, plus arugula, spinach, and many kinds of lettuce. Ahead of the summer harvest, farmers are offering green garlic — the immature stalk of the garlic plant that adds an incomparable zip to whatever it touches. It won’t be long before radishes and peas come along; and soon after, strawberries, tomatoes, eggplant, and other glories of the hot months. Already, there’s plenty of raw-milk cheese, and a host of farms offer delicious pastured pork and poultry — as well as grass-fed lamb and beef — along with their veggies. Several farmers cook up samples of their sausage, perfuming the air with savory scents.

While taking in this scene recently, I got to thinking of the minor stir I created in my last column, when I argued that higher prices for industrial food won’t necessarily inspire more people to choose sustainably grown, healthier fare. Instead, I claimed, the price squeeze will likely push people deeper than ever into the clutches of large-scale food marketers, companies that know how to economize on ingredients and labor costs while producing stuff people like to eat. Since then, I’ve pointed in Gristmill to fast-food execs hailing high commodity prices as good for business, and cash-strapped school-cafeteria administrators spurning fresh fruit for pre-fab cookies.

Annoyed by my analysis, several readers confronted me with a question: If higher commodity prices won’t “level the playing field” between industrial and sustainable food, what will? How can we convince more people to think outside of the Big Box, and to flee the Golden Arches?

Leveling the Playing Field

Standing amid the clamor, the scents, and the conversations of markets like the one in Carrboro, it’s easy to forget the massive built environment for industrial food that surrounds us: fast-food outlets by the hundreds of thousands, massive supermarkets hawking aisle after aisle of processed “food,” school and hospital cafeterias serving up not fresh-cooked fare but rather reheated, boxed pap and pabulum — to the very folks who could use a good meal most.

Why does industrial food dominate the culinary landscape?

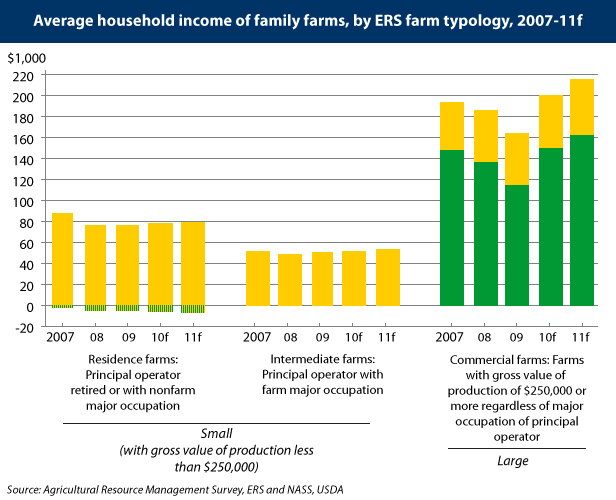

Chart: USDA

Chart: USDA

The more I think about it, the more the question seems to come down to supply and infrastructure. No matter what happens to industrial-food prices, “good, clean, and fair” food (to use Slow Food’s rhetoric) won’t conquer the American diet until we produce more of it and have the means for distributing it.

Even in places like Chapel Hill/Carrboro, the incredibly vibrant local-food scene is essentially confined to the farmers market and a few visionary, and necessarily relatively expensive, restaurants. Conventional supermarkets offer an abysmal sea of industrial-food “choices,” and the area’s food co-op and Whole Foods branch, for all their buy-local marketing rhetoric, sell mostly industrial-organic fare hauled in from long distances.

Nationwide, farmers markets and other local-food institutions, for all their vibrancy, generally remain niche operations catering to a relatively tiny portion of the population. The Kellogg Foundation (no longer related to the industrial-food giant famous for its corn flakes) reckons that nationwide, just 2 percent of food consumed truly qualifies as sustainable.

One reason: although the farmers market model works well for farms small enough to sell all or most of their produce directly to consumers, it makes only limited economic sense for mid-sized family farms. And it’s precisely these mid-sized farms that could ramp up local and regional food chains to a point where they supply a large part of the American diet.

Middle of the Story

So why isn’t that happening?

It’s not for lack of numbers. According to a 2007 USDA study, the U.S. now houses just under a million “working farms” — that is, farms generating at least $10,000 in annual revenue. And mid-sized farms — those with annual revenues between $50,000 and $250,000 — represent fully a third of that total. In fact, they outnumber large farms (those bringing in more than $250,000) by about two to one.

The problem, rather, is market structure. In the United States today, there are essentially two marketing channels for farms. You can sell your produce directly to consumers, through farmers markets and CSAs; or you can sell it to gigantic corporate buyers that have tremendous leverage to set price. The former model works well enough for small farms; the latter works best for large operations tightly focused on one or two crops — mostly corn and soy.

In that light, it’s not surprising that spaces like Carrboro Market brim with the bounty of small farms, and our supermarket shelves groan with goods that amount to clever combinations of processed corn and soy. As a group of agriculture scholars led by Fred Kirschenmann wrote in a seminal paper called “Why Worry about Agriculture of the Middle?” [PDF] mid-sized farms get squeezed in this arrangement. They are “too small to compete in highly consolidated commodity markets, and too large … to sell in direct markets.”

As a result, they operate under severe pressure. The above-linked USDA document tells a grim story. Despite the fact that mid-sized farms make up a third of working farms at present, we are losing them at a rate of more than 10 percent every five years. Meanwhile, the number of large and mega-farms is growing robustly.

Between 1997 and 2003, for example, 10.9 percent of farms with revenues between $50,000 and $99,000 closed their barn doors, as did 11.2 percent of farms bringing in between $100,000 and $249,000. Over the same period, the ranks of mega-farms with revenue exceeding $5 million swelled by 42 percent.

Another USDA study [PDF], this one from 2006, illustrates the obliteration of mid-sized farms in stark economic terms. On average, farms with revenues between $100,000 and $249,000 have an operating profit margin of negative 1.8 percent. Their operations lose money or make very little, and they augment family income with off-farm work. By contrast, farms that do between a quarter and a half million in business have operating profit margins of 10 percent, and farms with revenue of more than a half million have an average margin of 16 percent.

These large-scale farms don’t respond to the needs of their surrounding communities; to remain profitable, they toe the line laid down by the huge multinational food conglomerates that buy their crops. Mid-sized farms could fill the void between the farmers market and the grocery section of Wal-Mart at the local and regional level, but right now, the marketing infrastructure needed to move their goods to nearby consumers doesn’t exist.

As Kirschenmann et al put it, huge buyers of farm goods like Wal-Mart, Archer Daniels Midland, and to a large degree even Whole Foods have serious incentives to deal with only the largest farms. It simply costs less “to contract with one farmer who raises 10,000 hogs than ten farmers who raise 1,000 hogs,” they write.

Thus to break the stranglehold of industrial food over the American diet, we need to find new ways to connect consumers with mid-sized farmers. The infrastructure for doing so — locally owned grocery stores, dairy-processing plants, slaughterhouses, canneries — has withered away as the food industry consolidated over the decades. And farmers themselves, with their razor-thin if not negative profit margins, don’t have the resources to make those investments. Closing the gap between mid-sized farmers and their nearby communities counts, I think, as the major challenge of the sustainable-food movement going forward.

So far, the most promising efforts to meet that challenge have come at the local level. Last fall, I wrote about one such effort in Woodbury County, Iowa. There, farmers and consumers have worked hard to raise money to create a farmer-owned restaurant, processing center, distribution business, and grocery store — explicitly to give the area’s remaining mid-sized farms a viable market other than the one for corn and soy. All over the country, similar initiatives are bubbling up, and I’ll continue highlighting them.

“If present trends continue, mid-sized farms, along with the social and environmental benefits they provide, will likely disappear in the next decade,” Kirschenmann and his associates wrote several years ago. Since then, with the rise of the biofuel boom and the jump in corn and soy prices, those trends have intensified. As go mid-sized farms, so likely go the prospects for any real challenge to the myriad ravages of industrial food.