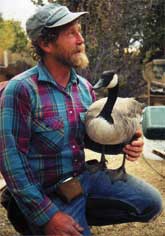

Skip Edwards is in his yard in rural Crawford, Colo., doing one of his favorite things: crawling behind Chaco, the goose he lives with. This is pretty much his job these days. She waddles. He crawls. He wants to learn her habits from the ground up.

Skip and Chaco — or is it Chaco and Skip?

When Edwards, a lifelong outdoorsman and recently celebrated environmental activist, drives off from the house, Chaco flies next to his red truck, sometimes with complicated consequences. When Skip and his partner Doreen Dethmers go rafting or kayaking, Chaco comes too, bobbing along in the rapids next to the boats. As for working, Skip has shelved that completely until Chaco returns to the wild.

“Doreen works, thank God,” says Skip, a boyish 54-year-old with bright blue eyes, laughing so explosively it sounds as though a machine may have blown up nearby.

Chaco started following Skip around last spring while he was on a river trip. After hours of searching unsuccessfully for her mother, he was faced with a decision: Should he leave the gosling to near-certain death by coyote, raptor, or rapid, or should he take her in? He doesn’t like messing with the natural scheme of things. But when he met Doreen that night, he reached into his jacket and produced a tiny handful of fluff with a bill.

“I said, ‘Oh, wow,'” smiles Doreen, a biologist, artist, and extremely understanding person.

Chaco now trails Skip like an adoring puppy, and pecks at the feet of visitors if they get too close to him. Skip hopes that when she reaches maturity this fall, her instincts will take over and she’ll return to the wild. Skip has a healthy appreciation for the wild.

From 1988 to 1993, Skip was a Bureau of Land Management river ranger on Utah’s Westwater Canyon, a stretch of the Colorado River whose remoteness and thumping rapids have gained it a cult following among whitewater enthusiasts. He and Doreen became passionate about the 17-mile stretch of river and red rock wilderness just west of the Colorado border. In 1995, when the BLM failed to adequately protect the first mile and a half of the canyon from a gold miner named Ron Pene, Skip went from admirer to activist.

Years before, the BLM had designated the 31,000 acres of canyon country around Westwater as worth studying for wilderness designation. But Pene successfully convinced officials to cut out 1,800 acres of the area — the first mile and a half of the canyon — from a proposed House wilderness bill that included Westwater. Pene argued that the upper portion of the canyon area didn’t qualify for wilderness consideration because it wasn’t pristine. He also had mining claims there, according to High Country News.

Utah desert wilderness has always made headlines, both for its beauty and its controversial politics. Congress hasn’t made a permanent wilderness designation yet, but over the last decade proposals have ranged from 1.1 million to 9.1 million acres. With such heady numbers being thrown around, a 1,800-acre sliver of land just a hair shy of the Colorado border was easy to miss in 1995.

But Skip Edwards was paying rapt attention. He quit his job, studied the intricacies of the 1872 Mining Law, the 1964 Wilderness Act, and a 1975 amendment to the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. He haggled with bureaucrats in Utah and bought a suit to wear while lobbying the power brokers in Washington, D.C. This spring, his agitating bore fruit. In a settlement with the Department of Justice, Pene abandoned his mining claims and agreed to remove all traces of his mining operation from the site. BLM officials will erase any other traces of mining by this fall. Westwater — all of it — is included in the latest 9.1 million-acre wilderness proposal from the Utah Wilderness Coalition.

Though his latest endeavor may seem more modest than his Westwater victory, Skip doesn’t think the two are incongruous. “This isn’t a diminishing of my environmental life,” he says of his time with Chaco. “It’s an extension of it.”