Dan Kent is the founder of Red Rock Forests. His work with Mexican spotted owls in the forests and canyons of southern Utah led to a growing awareness of the importance of Utah’s “mountain island” ranges to the surrounding desert watersheds and wildlife.

Wednesday, 12 Sep 2001

MOAB, Utah

This month begins Red Rock Forests’ second year as an incorporated nonprofit. We first began in the wake of the “salvage rider” that exempted three timber sales on Elk Ridge from public comment and appeal. (These were among the many, many timber sales nationwide that were exempted from environmental law by this rider, crafted by Mark Rey, the proposed undersecretary of Agriculture that will oversee the U.S. Forest Service.) Since then, there have been more timber sales and the creation of a local motor-sports group that has been building trails into remote parts of this district.

Dark Canyon Wilderness Area.

Photo: Tim Till.

As seems to be the case when working with government agencies, every little issue we work on in these small, relatively unspoiled southern Utah forests has strings tied all the way to Washington, D.C. Often, a debate over a single poorly designed project leads directly to federal policy, which is why so many enviro groups end up seizing on one issue, such as motorized use in the forest or restoration logging, and carrying the ball for the rest of us.

In Utah, statewide surges in spruce bark beetle populations have been the justification for a rash of uncoordinated and ghastly high-altitude timber sales, often called “Ecosystem Restoration Projects.” The Forest Service has given little consideration to the effects of this thoughtless assault on a problem that, in moments of candid honesty, it admits it has no weapons to fight. It’s a fact of life that mature spruce forests get outbreaks of spruce bark beetle. No big deal. Woodpeckers and other creatures thrive on this invertebrate feast. Our overly sanitized forests have been a tough place for decadence-dependant species to thrive in, such as the at-risk three-toed woodpecker, as decadence has long been frowned on as wasted productivity and a fire risk. This paradigm has been responsible for much of the loss of diversity in our forests.

Manti-La Sal National Forest.

Photo: Tim Till.

Fighting bad proposals by the Forest Service on scientific grounds is tough: At a minimum, it requires expert testimony and overwhelming scientific evidence to the contrary, as the agency is given the benefit of the doubt in these matters. What we need right now is a good database on spruce bark beetle research and an expert or two who can dismantle the shaky ground these spruce sales are built on. (Today I will call folks with the Sierra Club and Center for Biological Diversity in search of that expert.) Praises to the people who have had the foresight to do this for other issues, such as Road-Rip’s bibliography on the effects of roads or the Wilderness Support Center’s base of knowledge in crafting successful wilderness proposals.

As I go to work today on our comments on a proposed high-altitude timber sale just north of the Escalante/Grand Staircase National Monument, the events of yesterday are ringing in my head. The senseless loss of life drives home the need to remain peaceful in protest and respect all life. It also makes me realize that if our society had the same respect for all living things that we have for human life — at least American human lives — nearly all of our environmental problems would solve themselves. Even in action-oriented organizations like ours, the need to educate and extend human compassion beyond our species remains paramount.

Thursday, 13 Sep 2001

MOAB, Utah

Last night, I was asked to help a group that is organizing a peaceful protest of a massive, destructive oil exploration project on the border of Canyonlands National Park, right in the middle of one of the most visited parts of southern Utah. They are more than a little concerned about how they will be perceived in the wake of Tuesday’s terrorism.

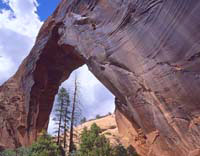

A great big arch in Manti-La Sal National Forest.

Photo: Tim Till.

Ed Abbey, an outspoken defender of Utah’s deserts against corporate extractive interests and development, always emphasized the need to distinguish between people and technology. He had no problem with the destruction of machines and technology in defense, but he drew a very sharp distinction between machines and living beings. In fact, his master’s thesis demonstrated the failure of violence against others to gain any of the goals of democracy. Ed put freedom of the individual and liberty first, which was perhaps even a larger motivator for him in fighting the forces of mass consumerism than the toll it takes on the environment, though I believe, as he did, that liberty and environmental protection go hand in hand.

Often, as an environmentalist, I am caught in this catch-22: Defense of the environment often seems to lead to greater restrictions, yet I revel in the freedom of the hills and seek out places on public lands that have yet to be completely tamed, with vault toilets, designated campsites, and neatly placed boulders at the end of the road. Yet with our growing population, insatiable energy consumption, and vehicles that are ever more efficient at penetrating the wilderness in pursuit of the wild, the unknown, the frontier, we have nearly pushed through the last wild places. In Utah, 95 percent of land in the state is within three miles of a road. We need to draw the line somewhere and allow nature to function unhindered by our most damaging incarnations, perhaps by limiting us to our own two feet if we want to visit those rare and splendid places that we have agreed to allow to persist as natural, functioning systems. Of course, we should be able to allow at least a minimum functioning of our rivers, oceans, and ecosystems everywhere, but there should also be many places left undimmed in their glory, cherished as genetic reserves for wiser times when the current wave of extinctions has reversed.

And so we consider our protest options, hoping that the world can distinguish between machines and human life: An attack on a destructive machine is very different than an attack on a human or other living thing. We also hope they can get beyond the mindset that says you must support all oil exploration and drilling, no matter where, how destructive, or how dangerous, if you use oil. We hope people can see that there are more and less appropriate places for development of any kind, and that Utah’s canyon country, with its smattering of dispersed, thickened desert oil, is not an appropriate place for oil rigs, pipelines, and 52,000-pound exploration trucks.

Friday, 14 Sep 2001

MOAB, Utah

Today is a big day for comment letters. Next Monday is the end of the comment period for four major items, including six grazing allotment plans, a 10-million-board-feet timber sale, the Uinta National Forest Draft Plan, and two rollerchop projects in virgin pinyon/juniper woodland. I can’t possibly do justice to these important issues, so I must try to prioritize time spent on them according to what we’ve told our magnanimous supporters we will be tackling. Perhaps even more important than commenting on these proposals: The newsletter is overdue, and we need to get our GIS road analysis map and roadless area inventory

to the Manti-La Sal forest engineer who is working on revising the forest travel plan. In addition to all this, I need to coordinate our little outing to a local peak this weekend, while trying not to let all the other pressing issues crowd in until I’ve cleared a few of these off my desk. Whew! Sounds more like a Monday than a Friday.

Southern Utahns are good at keeping this stuff secret.

Photo: Dan Kent.

It is hard to keep the goal in focus when there are so many potentially destructive projects occurring in our forests, and you are working alone on one small aspect of the whole. Of course, I think our corner of the world is the center of the universe, beautiful beyond compare, more worthy of protection than perhaps even my own mom. And thank goodness so many feel the same way about their corners of the universe. The computer and the web have strengthened one of the environmental movement’s greatest assets — shared information. The federal government regulates all public lands with the same stack of laws. Theoretically, that which improves public lands management in Alabama will also work in Alaska.

Shared information can allow small groups to be effective early on, if they tie in to the successes of veterans. Newcomers can also be effective just by virtue of the consideration extended to a fresh face, a new opportunity. Cynically, I must admit the only lasting successes we’ve had were when we made a stink in the media about the Forest Service working cooperatively with a group that was cutting ATV trails through sensitive, wildlife-rich parts of the forest. We found friends in the media who were willing to expose the misdeeds, and soon after we received four-page denials of any cooperative agreement to maintain and construct ATV trails involving the Forest Service. A trail that had been reopened after 30 years of no use and extended with no public comment was closed … temporarily, pending review. As the dust settled, the Forest Supervisor signed a clandestine contract nearly identical to the one they had just vehemently denied involvement with the month before. For people who believe in due process, that really burst our bubble.

A virgin forest in a steep, roadless municipal watershed that will be cut to “reduce risk of a bark beetle infestation” in the Abajo Mountains.

Photo: Dan Kent.

Being an impediment to forest destruction is necessary, but it gets old being a negative force, always jamming the gears of extraction and development. That’s why we’ve come up with something positive and proactive to do for our forest: We are developing a citizen’s alternative for the Forest Plan revision process. We are tapping the vast pool of knowledge and compassion in the biologists, recreationists, and other forest lovers in the area to design a management plan that will emphasize ecosystem health, self-reliance, and sustainability. We will construct this plan under the assumption that all life is sacred and deserving of respect. (Some people have questioned the need to extend this to mosquitoes and biting flies, but I think we can win them over once the skis have come out again.) Intangible values, such as the value of wild places to the health of the soul, and very tangible but ignored values, such as the importance of a fully populated, naturally self-regulating and interconnected, not isolated, system of wild areas, will help guide us. An ambitious project, but not a new idea — the Southern Rockies Ecosystem Project has created a fine model. The Utah Wilderness Coalition’s wilderness inventory criteria has also provided a fine model for our wilderness proposal, a key component of the citizen’s alternative and already complete.

All right, it might be an overwhelmingly busy Friday, but I feel like I’m sitting on the shoulders of giants. There is strength in diversity, and there is strength in sharing what we learn. Now, back to that fascinating section of the DEIS for the GSRMP detailing PFCs for the PCUs in the AERP.