Matthew Meyer is a third-year law student at the University of Michigan. In 1995 he cofounded the Wikyo Akala Project, which today sells used-tire sandals around the world at Ecosandals.com.

Monday, 14 Jan 2002

ANN ARBOR, Mich.

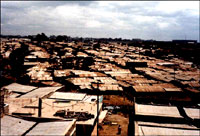

I first set foot in an African shantytown in 1992. As I walked through the Mathare Valley, a sprawling line of dilapidated huts and feces-laden alleys that hundreds of thousands called home, the images shocked me: People today should not be forced to live this way. As I spent more time in neighboring Korogocho, Nairobi, I learned that the poorest of the poor lead lives based almost entirely on re-using other people’s garbage.

A slum in Nairobi.

Photo: Matthew Meyer.

Being forced to live off other people’s trash is a tragedy, no doubt. But out of tragedy can come commercial opportunities for the people of Korogocho, as well as environmental lessons for the rest of the world. A few years ago, my friend Benson Wikyo and I started a community-based sandal-making operation that now sells globally and employs 27 sandal-makers from Korogocho. The sandals, made with durable soles recycled from old car tires, last five years or 50,000 miles. And they are providing an increasing number of unemployed young adults with job opportunities and rewards to last a lifetime.

Each day this week, I will write about Ecosandals.com, a website I started last year to promote the Wikyo Akala Project of Korogocho, Kenya. Growing up in the U.S., I always thought environmentalists and pro-growth economists were inevitably in conflict. The development of an aggressive capitalist business model, I thought, necessarily involved some amount of degradation of the Earth. But after nearly 10 years of working in the field, I have learned that environmental preservation and, more specifically, trash reduction, is critical to the provision of basic daily needs in materially impoverished urban areas in the developing world.

Making sandals in Korogocho.

Photo: Matthew Meyer.

Korogocho is one such place. There, being an environmentalist is less a selfless commitment to the Earth and more a commercial necessity. If you walk about half a mile from our workshop to the sprawling Mukuru landfill, you see thousands of young people, many under 10 years old, combing through the trash, looking for anything they can use or sell. In nearby Soko Mjinga, a large outdoor marketplace sells many of the wares found in the trash heap: old pipes and plastic bags, worn books, and old, half-broken cassette tapes. Virtually everything is wrapped in used newspaper. For the hundreds of millions of humans across our planet who live on less than $5 per day, scavenging through trash for food and anything of value is about survival. Yet, ironically, the great tragedy of mass poverty begets a culture of recycling and reusing that many in the developed world would do well to imitate. That is the cornerstone belief of the Wikyo Akala Project. And that is, in essence, the mission of Ecosandals.com.

Hours ago I arrived home from Nairobi, where I spent a month working with the project on-site. Over the next few days, I will bring you back to Korogocho with me, as well as take you on a quick safari through our Ann Arbor, Michigan, all-volunteer operation. My objective is to help you appreciate the people of Korogocho a little better, to see beyond a single image of wretched poverty and human tragedy, and to understand how some people become environmentalists out of necessity.

Tuesday, 15 Jan 2002

ANN ARBOR, Mich.

Korogocho, the town that is home to the Wikyo Akala Project, means “hopeless” in the local Kikuyu dialect. Korogocho families, with as many as 10 members, live in single-room huts made of mud or rusted sheets of iron. There is no sanitation system and no piped water. Refuse of all types litters the homes and their surroundings, and the stench of urine often wafts across the neighborhood. Disease runs rampant, as do gun-wielding thieves. The educational system, even at the elementary school level, is too expensive for most people to attend. In so many ways, all community structures have simply broken down. Virtually every week another child dies of a curable disease, and every few days a gun battle claims another victim — including one last Tuesday, just a few feet from our workshop. And so I repeat my mantra of yesterday, which became my mantra the first time I set foot in Korogocho: People should not be forced to live this way.

Sandal-maker Michael Karuri in front of his home with his family.

Photo: Matthew Meyer.

Some people in Nairobi are able to earn a decent living through panhandling. Literally thousands of children, many from Korogocho, learn from the earliest age that the surest path to survival is with hands outstretched. Young mothers and their children travel a few miles to downtown Nairobi and stay there for several days, hoping the occasional sympathetic passer-by will provide a few pennies to help put food on the table.

Our 27 sandal-makers, men and women who never had the opportunity to complete high school, have found another path to survival. The sandal-making project has helped people understand that creativity — in this case, a novel approach to the problem of overflowing trash — can be another ticket out of desperation. Our workers earn a living wage while helping to clear the neighborhood of refuse. The idea is catching on: One sandal-maker, Joel Chege, used some of the money he earned last year to start a small business recycling and reselling old plastic bags. Another, Mary Nyambura, a young mother of two, left the streets just last Thursday to join our project. “Don’t give to me,” Michael Karuri, another sandal-maker, likes to say. “Buy from me.”

Last week, Mercy Mureithi, a small business development advisor with Open For Business of Halifax in Nova Scotia, Canada, led a series of workshops for the sandal-makers. The primary goal was to enhance the entrepreneurial skill of the sandal-makers to help them consider their business prospects in a global context. One activity Mureithi led encouraged sandal-makers to think creatively. She gave them an old box. Working in small groups, the sandal-makers were to list potential uses of the box — different ways to reuse and market it. Many of the sandal-makers have not completed more than a year or two of formal schooling. Yet the exhaustive lists they created showed they had grasped one lesson as clearly as any development expert: that the creative use of existing resources can be the fastest route out of poverty.

Michael Karuri sells ecosandals to the mayor of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Photo: Matthew Meyer.

I arrived home from Nairobi Sunday night and am operating out of Ann Arbor this week. The tasks here are often menial, such as addressing customer concerns or performing regular maintenance on the website. But such involvement is ultimately about providing a gateway for the Korogocho people to the international marketplace, giving a global voice to a people who otherwise have none. Just one year ago, after six years of work, the Korogocho project was an eight-person operation struggling to pay its bills. In February of last year, Ecosandals.com went live. Within weeks, the project tripled in size. The sandal-makers were profiled in newspapers from Paris to Peoria and appeared on Canadian and Kenyan television, as well as on CNN.

We have not yet spent one penny on marketing, and we send all profits back to Korogocho. We only ask Chege, Nyambura, Karuri, and their team of 27 to think creatively and efficiently to produce high quality footwear from readily available resources. It is then our job here in Ann Arbor to give them voice, to help them access the global marketplace, and to enable the rest of the world to hear the voices of the Korogocho environmentalists as loudly as it does those at the United Nations Environmental Programme. Along the way, we are slowly building community pride and creative energy, a sparkle of hope in a place called Korogocho.

Wednesday, 16 Jan 2002

ANN ARBOR, Mich.

The office that houses Korogocho’s Wikyo Akala Project is hardly adorned with the accoutrements of modern efficiency. The office’s lone printer is broken, and has been for weeks. The phone does not work. The nearest photocopier is a quarter of a mile away. The people staffing the office communicate with the workshop (a mile away) by sending a messenger. Electricity is sporadic. In many respects, the office is struggling to function on a basic level, as is the case in so many Nairobi-area businesses.

Office fun.

Photo: Ecosandals.com.

Yet the Wikyo Akala Project operates a multi-national business, one that in recent weeks has sold sandals made from recycled tire rubber to customers in Sweden, Canada, England, and the U.S. Much of this is thanks to the Internet, which provides a way around the traditional barriers facing organizations with limited resources. There is no way our office could market the Wikyo Akala Project effectively without the Internet. But the seven-year journey to get this far has been meandering, and occasionally tragic.

Four years ago, our mission of selling eco-sandals nearly died along with my friend Benson Wikyo. Wikyo and I worked with Nairobi street children in 1994. When I received a startup grant for the sandal-making project from the Samuel Huntington Fund of Westborough, Mass., Wikyo was the perfect teammate to help me with the business venture. As a young Kenyan volunteer, he was uniquely able to get teams of troubled street youths to work together and think positively. In early 1995, we started the Korogocho Akala Project together. He remained in charge when I returned home to the U.S. later that year. For the following three years, the project struggled to survive. There were a few large orders and many small ones. The project barely provided irregular employment for three Korogocho sandal-makers.

Then, in 1998, I received an email from Benson telling me he was sick. A week later I received a fax that appeared to be the photocopy of a few scribbled words on the back of a chewing gum wrapper. A friend of Benson’s had sent a copy of the doctor’s certification than he had died. One friend told me it was typhoid. Another claimed it was meningitis. Either way, it was clear that, like so many others Benson and I had worked with in Korogocho, he had died an unnecessary death. Decades-old medical technologies could have saved Benson’s life, and countless others. But no one has the money to afford these technologies. Benson didn’t either, and so he died — and with him, I thought, the Korogocho Akala Project would die as well.

That’s me in the corner, helping to make sandals.

Photo: Ecosandals.com.

But within a month of Benson’s funeral, I received a proposal written by his friend Patrick Mukoya. He did not want the project to die. He proposed a small seed grant to restart the project, renaming it the Wikyo Akala Project. Within a few months, the project re-started and developed beaded sandal styles that began to sell. The 2001 launch of Ecosandals.com enabled the project to flourish. Within a month of the launch, the Korogocho sandal-makers were receiving email messages and orders from around the globe. The project quadrupled in size and now employs nine young mothers in addition to 18 young men, providing them with a steady income. All sandal-makers have access to the Internet and will soon be involved in directly marketing the sandals to customers globally. One online customer brought two Korogocho residents to Canada for business training.

The project is slowly emerging as a model of how electronic commerce can benefit communities in the developing world. So often, people in places like Korogocho look far away for their development solutions. The Wikyo Akala Project and Ecosandals.com encourages Korogocho residents to use creativity and look inwards for solutions to local problems. Moreover, we encourage solutions that bring both economic and environmental benefits to the community. Our office produces virtually zero waste and hardly uses any electricity — although admittedly, less by design than by the realities of a broken printer and a dysfunctional electric company. Yet it is promoting a self-sustaining operation that is gaining momentum with each online order.

Thursday, 17 Jan 2002

ANN ARBOR, Mich.

Each time I travel to Kenya to visit the Wikyo Akala Project, sandal-makers invite me over for lunch. Such hospitality is common throughout East Africa; in fact, there is a Swahili saying that a visitor is a blessing. There is a Matthew Meyer saying that people who offer me food are a blessing. So we get along well, although the sandal-makers probably end up having me as a lunch guest far more often than they ever intended.

The team.

Photo: Ecosandals.com.

The Korogocho diet is largely vegetarian, as meat is prohibitively expensive, so the lunches generally consist of ugali (a Kenyan corn-based staple) and sukamawiki (flavored greens that are said to give you strength). Usually the lunches are little feasts, with as many as 10 friends and family members of the sandal-maker joining us. We wash our hands, say a brief prayer, and then dig in to communal plates at the center of the table. A few extra kids often miraculously appear to assist once we start eating the food.

But last week, when I went to the house of a sandal-maker named Maina, there was no such feast or fanfare. Maina served us alone. There was no family around. Two other visitors and I had a few pieces of bread and sodas. Maina’s home, like that of all the sandal-makers, is a simple one-room structure. The bed is set off from the sitting area with a curtain. A little gas stove and two pots in the corner of the room constitute the kitchen. With the exception of his bed and sofa, all of Maina’s material possessions could probably fit in the backpack I carried to his home that day.

“Where is your mother?” I instinctively asked. He was silent for a moment, and in that interval I remembered that Maina’s mother had died over a year ago, while I was back in Michigan.

Several of the sandal-makers.

Photo: Ecosandals.com.

Death — from AIDS, typhoid, cholera, childbirth, car accidents — casts a ubiquitous shadow over Korogocho. Few sandal-makers have two living parents. Of the five that have been with the project the longest, three have recently lost an immediate family member. This makes it easy for me to explain to potential customers in the U.S. why buying sandals at Ecosandals.com is important — why it is critical to help provide money for housing and education and medicine to the people of Korogocho — but it didn’t make it any easier for me to sit across from Maina, foot in mouth, and understand his pain.

Still, Maina gracefully thanked me for joining him for lunch and explained that sandal sales had paid for the soda I drank and the bread I ate — not to mention the room I sat in and, he said, even the smile on his face. That’s good news, obviously, but we still have not sold enough to pay Maina as much as we (or he) would like. Maina’s mother died during his initial three-month training period, and simply paying his $10 monthly rent became a huge chore. Fighting personal tragedy is always difficult; doing so when the tragedy has taken away the hand that feeds you can be devastating. But Maina learned to cope without his mother. He works hard and pays his own rent. His peers consider him a leader in the project. Sandal-makers are guaranteed 30 percent of all profits, which enables Maina to earn as much as $50 per month.

By local standards, that’s a decent wage — but it doesn’t mitigate the living conditions in Korogocho, to which no human being should be subjected. Death, disease, malnutrition, illiteracy, and violent crime are just a few of the challenges that confront the sandal-makers virtually every day. Still, I have learned, over time, that we cannot solve all of Maina’s problems at once. What we can do is offer a friendly and interesting workplace, a greater understanding of environmental and economic sustainability, and the financial and personal rewards of hard work. It is not enough, but it is something; for Maina, at least, it has been of help during a difficult year.

Friday, 18 Jan 2002

ANN ARBOR, Mich.

There are over 6 billion people on this planet. Many of them, at least several hundred million, recently migrated from rural to urban environments in the developing world. In cities like Nairobi, most basic systems — sanitation, transportation, water, communications — have been unable to keep pace with the population growth. Sewage literally runs through the streets in Korogocho, and clean water is sold in alleyways as a precious commodity. The Nairobi River that meanders beside the slum is filthy, and continues to serve as a public bath for millions and a public toilet for many others.

Korogocho children picking through trash.

Photo: Ecosandals.com.

I have always felt that environmentalism in a place like this has to involve forging long-term solutions to existing human problems. Almost everyone would agree that environmentalism is a commitment to leave the planet in better shape for our children. For sandal-makers like Roselyn Egosangwa, who has five children of her own, that sentiment takes on much more urgency. Being an environmentalist in Korogocho is not about saving the planet for generations to come; it is about providing a better life for Roselyn and her five children today.

The collection of volunteers who assist with Ecosandals.com live far, far away from Korogocho, and the work we do — internet marketing — is a world away as well. Today, my volunteer duties include responding to a potential customer who has a size 9 left foot and a size 9 1/2 right foot. (I need to determine if and how she can place an order online.) I’ll also talk to Canadian and British sandal distributors that want us to link to their websites. In addition, I’ll help handle the day-to-day details that enable a Korogocho-based multinational business to continue running smoothly.

Project co-founder, the late Benson Wikyo.

Photo: Ecosandals.com.

Although the work we do here in Michigan is far removed from Roselyn and Maina and the environmental consequences of mass urban migration, the livelihoods of people a half a world away depend on what we do. Our success determines their ability to recycle tires from Nairobi landfills in order to earn enough money to access clean water and decent health care. We are eco-friendly in an American way, trying to reduce our paper use and turn the lights off when we leave the room. They are eco-friendly in a Kenyan way, operating a paperless office because of a broken printer, living with flickering lights due to sporadic electricity, and surviving by selling anything of quality they can make from the scraps society leaves for them.

Collectively, ours is an environmentalism that believes economic growth and environmental preservation must work in concert. It is difficult to expect people to nurture their ecosystem if they do not know whether their children will have food to eat that day. Therefore, if we want environmentalism in Korogocho to move beyond what is demanded by the basic necessities of life, then first we must meet those basic necessities. That is what the Wikyo Akala Project is trying to do. In a most literal way, the sale of recycled sandals promotes the wise use of resources. But the most important work we do on behalf of the environment is recycle hope by bringing it back to a people who named their own community “hopeless.”