Put that chocolate down, hold the wine and roses, and take yourself back to the dark side of Valentine’s Day. You remember, that day your sophomore year in high school that began with the discovery of a new 18-megawatt zit and ended in tragedy when [insert teen proto-love interest here] said they wouldn’t go out with you if you were the last person on the planet.

I know, this harsh remembrance is not exactly sanctioned by the good folks at Hallmark or FTD, but do it anyway. Do it for the whooping cranes. With barely 200 living in the wild and fewer than 100 scattered at a handful of captive sites, this ancient and imperiled bird is living that nightmare. If you think it’s challenging to locate a soul mate on a planet overrun with 6 billion of your species, at least you’ve got options. One can only hope the whoopers don’t really know the depth of their predicament: talk about performance anxiety!

Raising Crane

It is the good fortune of whooping cranes that George Archibald does not suffer from performance anxiety. Archibald cofounded the International Crane Foundation in 1973, and has since turned the headquarters in Baraboo, Wisc., into a nexus for worldwide crane conservation efforts.

In the early 1980s, Archibald played suitor to Tex, a mildly dysfunctional whooping crane who had spent far too much time as a house pet. “Tex got pretty old before she saw other whooping cranes,” explains Scott Swengel, ICF’s curator of birds. “The older a crane gets before it sees another opposite-sex individual, the harder it is to pair it. She was hopeless by the time we got her. She was completely in love with men. George understood enough about crane behavior to realize that she needed to think she was paired to lay an egg. Whatever it was she was paired with, it didn’t matter. So he figured he would just have to spend his own time dancing with her. She really liked him.”

The dancing was successful, and with a little whooper semen flown in from Maryland’s Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Tex laid her first fertile egg. It was also her last. Just 24 days after the egg hatched, Tex was killed by a raccoon.

Archibald’s ministrations to Tex were extraordinary, but other ICF staff members also go to great lengths as they play Cupid, pairing up cranes and working to preserve as much genetic diversity in captive populations as possible, with the ultimate goal of safeguarding wild populations. In the sprawling pens of ICF’s Crane City, all 15 species of crane have been successfully bred.

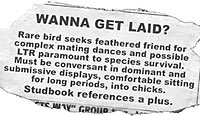

A matchmaking session begins with a look at the studbook, which contains the known lineage of all the captive birds of a species. From there, a bird’s relative importance to the gene pool is assessed. The math is complicated, but generally speaking the fewer living relatives a crane has, the more valuable it is. “I’m thinking about it always,” says Swengel. “The extreme measures that we’ll take to get a bird paired is proportional to how valuable it is genetically.”

There is some room for true love amid all the chromosome counting. For example, when the studbook keeper for Ginger and Bubba, a pair of whooping cranes, suggested that the two might not be the best genetic match, Swengel didn’t want to break up the amorous couple. “I don’t want to lose a pair that lays eggs every year and can raise chicks for us and possibly have one of them hurt their new mate. They’re both really mean and strong birds.”

Matchmaker, Matchmaker, Make Me a Hatch

ICF staffers always take a close look at records about birds’ past social endeavors, down to minute observations about how the cranes behaved during previous social engagements. Matchmakers can’t be cavalier because the stakes are high. In the wild, when a date goes poorly, one or both birds simply fly off. In the Crane City pens, where the cranes can’t leave, a bad date can lead to a battle to the death.

When aviculturist Tori Kaldenberg began efforts to unite two Siberian Cranes, Lance and Moda, she proceeded with appropriate caution. After the birds had spent some time in adjacent pens, Kaldenberg decided that they were ready for a first date. She brought Moda, the male, to Lance’s pen and watched as the two hovered like nervous teens, standing not too close but not too far away. Yet something wasn’t quite right: When Moda threatened Lance, she would back away or retreat. “They seemed to be interested in each other but she still was just a little too submissive.”

It turned out that all she needed was a set of high heels. Kaldenberg built a mound right where Lance normally stood. “She would use the mound, and I think it gave her the feeling that she was a little more dominant,” says Kaldenberg. The birds grew more comfortable until finally they were always within 10 feet of each other.

Next Kaldenberg let them spend every day together for a week and a half. “When we separated them for the night, probably the last three or four times, she would always give us a threat.” It was clearly time for the sleepover. “Once they’ve spent the night together, they’re pretty much married. It’s like letting your teenager go out for a date the first time. You can’t monitor them at night.” The very next morning, Lance and Moda became an official item.

The cranes are more like humans than you might imagine. For example, there are pairs that are just friends. “The challenge is for us to recognize those before we’ve spent eight years waiting” for them to mate, says Swengel.

Then there are the nut cases, somewhat like those couples that do well enough together, yet you pray they never have kids.

For example, Lance’s former love interest, Bazov, took fatherhood a little too seriously: He wanted to incubate everything. “He would even invent things to incubate, he wanted to incubate so bad,” says Swengel, and his odd behavior intimidated Lance. “She would be over at the far side of the pen acting like she was afraid of the whole thing, and he would be there sitting on nothing. Even though they got along fine as cohabitants, their dynamic about what was going to happen when eggs were laid was totally screwed up.”

But while Bazov may have been a bit of a pill with Lance, all it took was a little amorous alchemy to make a happy ending. “We found a different female [one Dr. Saab] who was more experienced and used to incubating,” says Swengel. “We put ’em together and they mated and raised a chick all in the same year. Both Lance and Bazov got new mates, and I think both of them are happier.”

The Take-Home Lesson

Are there any secrets stored away in the ICF Kama Sutra that you might use to liven up your love life?

For starters, shower regularly. Brolga and Saurus cranes breed in sync with the rains, so ICF uses sprinklers on timers to simulate a rainy se

ason for these tropical cranes. Use mood lighting. The breeding cycle of Siberian cranes is triggered by the length of the Arctic days, so ICF simulates an Arctic night.

And you can’t beat slow dancing. Crane mating rituals are more complex than we can get into here, but try to imagine those long necks and wings and legs prancing and unfurling in timeless pursuit of procreation.

You might even want to bring your date to ICF for vetting by the birds. Swengel insists that the cranes are far more perceptive about us than we are about them. “They can tell if you like the person that’s with you, and they can also tell if it’s your mate or not your mate. And they can tell if you’re married; they can tell if you ought to be married, or shouldn’t be married. People who have bad marriages? They don’t even treat you like you’re married.”

Could it be that we’ve got it all wrong, that the cranes should be making matches for us, and not vice versa?

“Probably,” says Swengel, chuckling. But it’s no joke. “Wild animals apply themselves more to understanding human behavior than humans apply themselves to understanding wild animal behavior.”