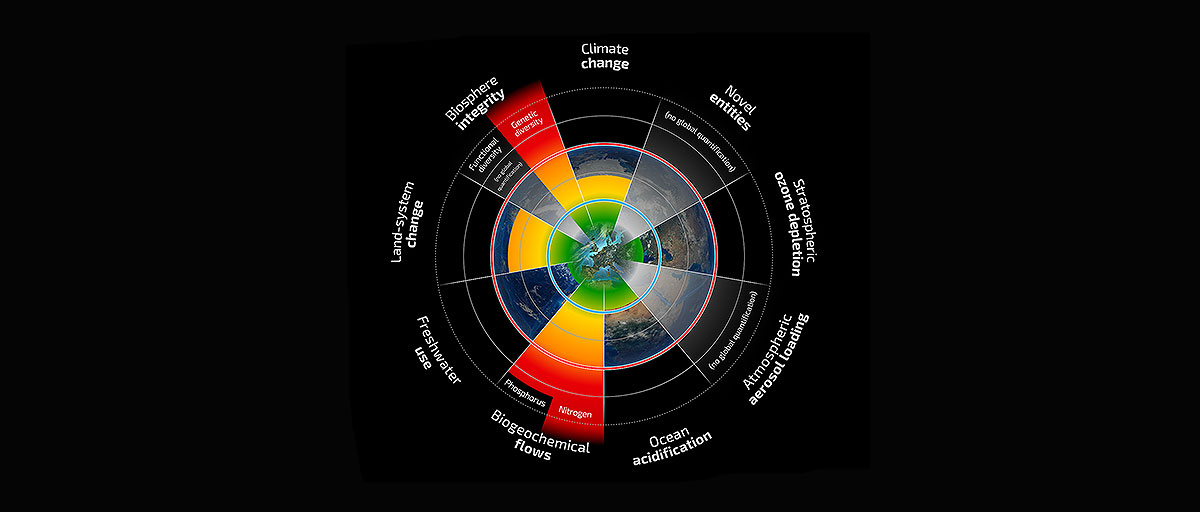

Some think nitrogen pollution may be the greatest danger we face. The Stockholm Resilience Center, an organization that examines the largest threats to natural life-support systems, considers our overuse of nitrogen a more extreme risk to life on Earth than climate change.

But a new paper, published in the journal Nature this week, uncovered a way that we could keep millions of tons of nitrogen fertilizer from evaporating into the atmosphere and running into the oceans.

Nitrogen is a basic building block of our food, so farmers spread tons of the stuff — in the form of manure, compost, and synthetic fertilizer — on their fields. But only half of this nitrogen makes it into plants. The rest gets chewed up by hungry soil bacteria and turned into a greenhouse gas 300 times worse than carbon dioxide, or gets washed into waterways where it fuels an explosion of algae growth that turns into lakes and oceans into gloopy, oxygen-starved dead zones.

It’s a massive problem that doesn’t get enough attention. If the Earth were a spaceship [eds note: isn’t it?], the control panel’s nitrogen light would be flashing red.

The Stockholm Resilience Center’s estimation of planetary boundaries F. Pharand-Deschênes/Globaïa

Humans accelerated the nitrogen disaster during the “green revolution” of the 1960s with the worldwide adoption of fertilizer-hungry crops. These replaced strains of wheat, rice, and other grains that grew more slowly and conservatively. Grain harvests more than doubled in two decades, but clouds of pollution spread into the air and water. It seemed like a vicious tradeoff.

But this new research suggests that crops can be nitrogen-hoarding and high-yielding at the same time. Before this study came out, it seemed like we had to choose between frugal crops that grow slowly and hoard nitrogen, and spendthrift crops that grow quickly require extravagant nitrogen.

What had looked like a trade-off may simply have been a mistake. The scientists identified a gene that inhibits nitrogen absorption in rice, which had become hyperactive in high-yielding strains, and figured out how to counteract it. This gene (metaphorically) shouts, “Don’t suck up nitrogen!” Through breeding, scientists were able to turn down the volume of this shout to a whisper. The result is high-yielding rice that needs less fertilizer.

A rice-breeding program to bring this breakthrough to farmers is underway in China, where nitrogen pollution is especially bad. It will take about five years before we really know if this works for farmers outside of greenhouses and test plots. If it does, it might change that nitrogen warning on spaceship earth’s dashboard from red to yellow.