For the 2004 presidential race, the Green die is cast.

“The Green Party emerged from a national meeting … increasingly certain that it will run a presidential candidate in next year’s election, all but settling a debate within the group over how it should approach the 2004 contest,” the Washington Post reported on July 21. The Green Party promptly put out a news release declaring that Greens “affirmed the party’s intention to run candidates for president and vice president of the United States in 2004.”

That release quoted a national party co-chair. “This meeting produced a clear mandate for a strong Green Party presidential ticket in 2004,” he said, adding that “we chose the path of growth and establishing ourselves as the true opposition party.” But other voices, less public, are more equivocal.

Days later, national party co-chair Anita Rios told me that she’s “ambivalent” about the prospect of a Green presidential race next year. Another co-chair, Jo Chamberlain, mentioned “mixed feelings about it.” Theoretically, delegates to the national convention next June could pull the party out of the ’04 presidential race. But the chances of that happening are very slim. The momentum is clear.

Few present-day Green Party leaders seem willing to urge that Greens forego the blandishments of a presidential campaign. The increased attention — including media coverage — for the party is too compelling to pass up.

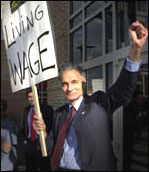

Ralph Nader during the 2000 presidential race.

Photo: Nader 2000.

In recent years, the Greens have overcome one of the first big hurdles of a fledgling political party: News outlets no longer ignore them. In 2000, the Green presidential ticket, headed by Ralph Nader, had a significant impact on the campaign. Although excluded from the debates and many news forums, candidate Nader did gain some appreciable media exposure nationwide.

Green leaders are apt to offer rationales along the lines that “political parties run candidates” and Greens must continue to gain momentum at the ballot box. But by failing to make strategic decisions about which electoral battles to fight — and which not to — the Greens are set to damage the party’s long-term prospects.

The Green Party is now hampered by rigidity that prevents it from acknowledging a grim reality: The presidency of George W. Bush has turned out to be so terrible in so many ways that even a typically craven corporate Democrat would be a significant improvement in some important respects.

Fueled by idealistic fervor for its social-change program (which I basically share), the Green Party has become an odd sort of counterpoint to the liberals who have allowed pro-corporate centrists to dominate the Democratic Party for a dozen years now. Those liberal Democrats routinely sacrifice principles and idealism in the name of electoral strategy. The Greens are now largely doing the reverse — proceeding toward the 2004 presidential race without any semblance of a viable electoral strategy, all in the name of principled idealism.

Anita Rios parties green.

Photo: Green Party.

Local Green Party activism has bettered many communities. While able to win some municipal or county races in enclaves around the country — and sometimes implementing valuable reforms — the Greens stumble when they field candidates for statewide offices or Congress.

When putting up candidates in those higher-level campaigns, the Greens usually accomplish little other than on occasion making it easier for the Republican candidate to win. That’s because the U.S. electoral system, unfortunately, unlike in Europe, is a non-parliamentary winner-take-all setup. To their credit, Green activists are working for reforms like “instant runoff voting” that would make the system more democratic and representative.

In discussions about races for the highest offices, sobering reality checks can be distasteful to many Greens, who correctly point out that a democratic process requires a wide range of voices and choices during election campaigns. But that truth does not change another one: A smart movement selects its battles and cares about its impacts.

A small party that is unwilling to pick and choose its battles — and unable to consider the effects of its campaigns on the country as a whole — will find itself glued to the periphery of American politics.

In contrast, more effective progressives seeking fundamental change are inclined to keep exploring — and learning from — the differences between principle and self-marginalization. They bypass insular rhetoric and tactics that drive gratuitous wedges between potential allies — especially when a united front is needed to topple an extreme far-right regime in Washington.