Oil refineries are a well-documented source of air pollution, but less attention is paid to the ways they also pollute the water. Transforming crude oil into petroleum produces millions of gallons of wastewater each day, filled with toxic chemicals and heavy metals, that pours out of the plants and flow into rivers and streams affecting nearby communities.

While the Environmental Protection Agency is legally required to regulate these pollutants and impose penalties, a new study released Thursday by the Environmental Integrity Project maintains that hasn’t been happening.

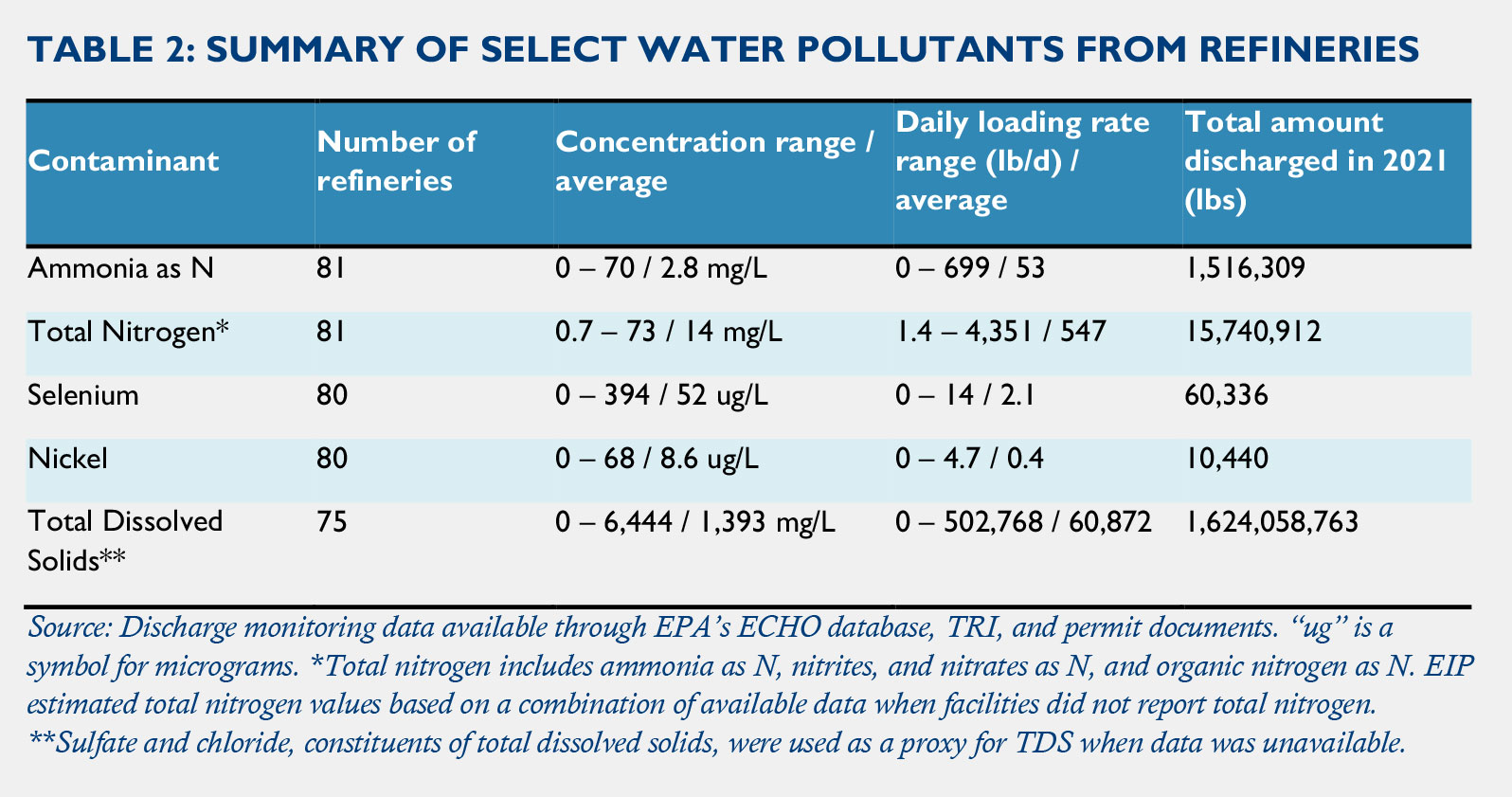

The project’s analysis looks at monitoring data, permit applications, and toxic release reports from the nation’s 81 oil refineries that discharge their waste into waterways directly or through off-site treatment plants. In 2021 alone, the plants released a total of 60,000 pounds of selenium, known to cause mutations in fish, and 15.7 million pounds of nitrogen, which feed harmful algal blooms. Some 10,000 pounds of nickel, also toxic to fish in trace amounts, streamed into waterways as well, plus 1.6 billion pounds of chlorides, sulfates, and other dissolved solids that can corrode pipes and contaminate drinking water.

The totals in the report do not include contaminants released in stormwater runoff or spills that bypass water treatment systems, noted Eric Shaeffer, executive director of the Environmental Integrity Project who previously served as director of the EPA’s Office of Civil Enforcement. “We think we’re understating the problem,” he said.

Most of this pollution, the report found, happens in places where people have fewer economic resources and political influence to push back. More than 40 percent of the refineries in the study are located in communities where the majority of residents are people of color or considered low-income.

John Beard, executive director of the Port Arthur Community Action Network, which advocates for environmental justice in the refinery-dense communities east of Houston, Texas, joined a press call for the report. “They don’t build these facilities in Beverly Hills or River Oaks, Texas, and places that have a way and a means to seek justice and correction,” he said. “They take the ‘path of least resistance,’ [building near] people who can ill afford to fight back.”

The “witches’ brew,” as the report calls it, flowing out of these refineries poses a real threat to aquatic life and communities. Wastewater from two-thirds of the refineries studied contributed to the “impairment” of downstream waterways, meaning they became too polluted to drink, fish, or swim in, or support healthy aquatic plants and animals.

Yet much of this pollution is actually legal, the Environmental Integrity Project points out.

The federal Clean Water Act requires the EPA to limit industrial discharges of 65 toxins, but in fact they regulate only 10 pollutants for refineries. The agency is also supposed to update its limits every five years as technologies to treat wastewater improve, but the rules for refineries have not been changed since the 1980s. In addition, refineries are now twice the size on average than they were when those regulations were last made.

While the EPA does have rules about ammonia, for example, they are not reflective of the current technology that makes refineries capable of much lower discharge rates of the compound. And there are no limits to the amount of selenium, benzene, nickel, lead, cyanide, arsenic, mercury, and PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, known as forever chemicals, that can come out of these facilities.

When it comes to the outdated rules the EPA does have for refinery wastewater, the agency has repeatedly failed to enforce them. The Environmental Integrity Project found that 83 percent of U.S. refineries violated regulations on water pollutants at least once between 2019 and 2021. The EPA is supposed to fine violators, but less than a quarter of the refineries received any penalty. One of the worst offenders, Hunt Southland Refinery in Lumberton, Mississippi, violated water pollution limits 144 times during the study period, but was subject to just two penalties, amounting to fines of $85,500. The Phillips 66 Sweeny refinery near Houston, Texas, exceeded its limits 44 times, mostly for excess cyanide, but was only penalized once.

States also have authority to regulate refinery wastewater through permitting, but they often look to the EPA guidelines in setting their rules. While a few have included additional limits, the report notes that these are also rarely enforced. The EPA has made recent headlines for being short staffed and falling far behind on its own deadlines to create dozens of regulations that are central to the President’s climate goals, despite a new injection of funds from the bipartisan infrastructure law and the Inflation Reduction Act.

“What are we asking for? No more than what the Clean Water Act has required since the 1970s,” said Shaeffer. “We ask the EPA to comply with the law, rise to the occasion, and write new standards based on the advanced treatment systems we have in this century, instead of the ones we should have left behind in the last one.”