In the early 1980s, America’s biggest company knew more about climate change than basically anyone else. Rising emissions posed a threat to Exxon’s business — selling fossil fuels — so the oil giant took the lead on understanding what was called the “CO2 problem.”

At the time, Exxon was pouring $900,000 a year into researching the effects of burning fossil fuels. It took an oil tanker, revamped it into a research vessel, then sent it on long journeys around the Atlantic Ocean to measure how the ocean was absorbing rising carbon dioxide emissions. In 1982, the company pivoted to a cheaper approach and directed its scientists to create mathematical models that calculated how rising carbon dioxide levels would change life on Earth in the coming decades. They turned out to be eerily accurate.

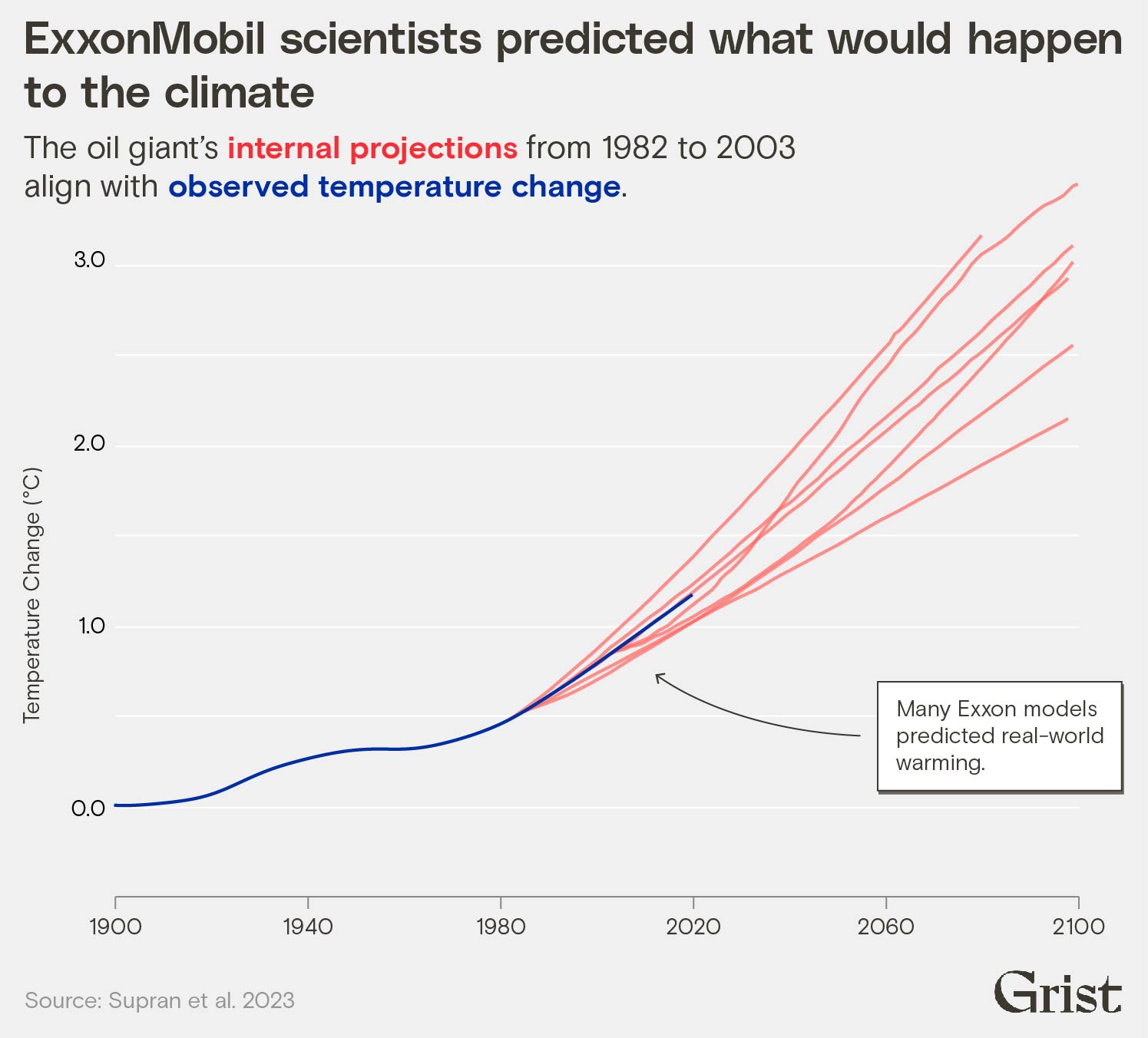

A study published in the journal Science on Thursday is the first to systematically measure how those models matched up against the real world. Researchers at Harvard University and the University of Potsdam in Germany found that Exxon’s estimates from 1977 to 2003 proved to be just as precise as those from independent academics and government scientists. Between 63 and 83 percent of Exxon’s projections, depending on how they’re measured, accurately predicted how the world would warm in the coming decades. The study could provide fresh support for lawsuits against ExxonMobil by quantifying just how well the company understood the threat of the climate crisis decades ago.

“It kind of took my breath away when I actually plotted for the first time Exxon’s predictions, and you see them land so tightly around that red curve of reality,” said Geoffrey Supran, a co-author of the study who researched fossil fuel propaganda at Harvard and is now a professor of environmental science and policy at the University of Miami.

The chart below shows how global warming projections modeled by Exxon scientists compared to the actual temperature that ensued.

The study comes at a time when oil giants are under pressure to curb carbon pollution and prepare for a future powered by renewables like wind and solar. Activist shareholders have gained seats at oil companies including ExxonMobil, seeking to align their business strategies with the climate crisis. Harvard, Princeton, and other prominent universities are getting rid of investments in fossil fuels. With floods, fires, and smoke growing noticeably worse, a social reckoning is at hand: Young people are turning away from careers in the stigmatized oil and gas industry.

At the beginning of the 1980s, Exxon’s own scientists had warned that continuing to burn fossil fuels would lead to “catastrophic” and “irreversible” consequences. But starting in 1989, Exxon publicly dismissed its own findings. The company’s leadership cast doubt on the credibility of climate science, deriding models and emphasizing how “uncertainty” made them virtually useless. It’s part of a larger story about how many companies — including Shell, coal companies, and utilities — misled the public about climate change while their executives understood and downplayed the dangers of skyrocketing carbon emissions.

Evidence of this deception has become the basis for dozens of lawsuits against fossil fuel giants in recent years, with cities and states seeking to hold companies and governments responsible for damages from climate change. So far, most have failed, with some exceptions that force countries or companies to make deeper cuts to their carbon emissions.

Supran suspects that the new quantitative evidence about what Exxon knew — and when — could prove to be compelling evidence in lawsuits. “I imagine that both in court, and then of course in public opinion, simple visuals proving Exxon knew and misled on climate may prove powerful,” Supran said.

The study finds other examples of how Exxon’s scientists foresaw the future. They accurately predicted that the scientific community would become confident that human-caused global warming was underway around the year 2000, the median estimate of nearly a dozen speculative reports Exxon conducted 15 to 20 years earlier.

Exxon’s researchers also rejected the prospect of an impending ice age, a notion that was popular in news headlines in the 1970s, though not backed by many scientists. They also accurately forecasted how much carbon dioxide could be emitted while keeping global temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees F).

But Exxon’s public stance remained hostile to any public discussion of that same research. The company’s leadership and marketing team worked to create a cloud of confusion around climate science. In 2001, an ExxonMobil press release argued that there was “no consensus about long-term climate trends and what causes them.” In a 2004 New York Times advertisement, the company stated that “scientific uncertainties continue to limit our ability to make objective, quantitative determinations regarding the human role in recent climate change.” The following year, Lee Raymond, then ExxonMobil’s CEO, blamed sunspots and the wobble of the Earth for global warming during a PBS interview, claiming that scientists didn’t know if humans played a role in changing the climate.

The latest study focused on Exxon because of its well-documented climate research program — which resulted in the largest public collection of global warming projections from a single company — and because of its long record of challenging climate science. Between 1998 and 2019, Exxon gave more than $37 million to organizations that sought to sow confusion about the scientific consensus around climate change and obstruct efforts by governments to take action.

In response to the study, ExxonMobil spokesperson Todd Spitler said that “those who talk about how ‘Exxon Knew’ are wrong in their conclusions.” He cited a ruling from a 2019 court case involving Exxon, in which a judge said that the New York State Attorney General had failed to provide enough evidence that Exxon broke the law by misleading shareholders about climate change. The judge who ruled in Exxon’s favor said at the time that the case was “a securities fraud case, not a climate change case.”

Casting doubt on the science was just one prong of Exxon’s approach. Previous research from Supran and Harvard historian Naomi Oreskes has shown that Exxon used subtle rhetoric to shift the blame for climate change from fossil fuel producers to the individuals who used them to power their cars and heat their houses. Another part of Exxon’s strategy was to highlight how climate policies could harm the economy while ignoring the enormous costs of failing to rein in emissions as well as the economic benefits of taking action.

The new study provides a fresh point of comparison in the history of deception from fossil fuel companies, Supran said. “It’s one thing to understand that they vaguely knew something about global warming decades ago, that they were broadly aware of the relationship between fossil fuels and warming, but to realize that they knew as much as anyone, as much as independent scientists did … it’s kind of shocking.”