This story was originally published by Slate and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

There was quite a lot of water in the streets of New Orleans on Wednesday morning, thanks to intense thunderstorms that prompted the National Weather Service to issue a “Flash Flood Emergency” warning. Parts of the city received nearly a foot of rain before noon, turning neighborhoods that rarely flood into canoe routes.

This the drainage canal beside Xavier University at Drexel. I’ve given up on getting to work for time being. City at standstill. pic.twitter.com/Ow9Mbk3mdD

— Mike Hoss Voice of Saints (@MikeHossComm) July 10, 2019

https://twitter.com/MaBamBa/status/1148951985636483073

Those scenes offer a preview of what’s to come later in the week, when a tropical depression is projected to turn into Hurricane Barry and make landfall on the Louisiana coast as a Category 1, dropping as much as 2 feet of rain in some parts of the state.

New Orleans has long had a problem with rainfall flooding, since much of the city sits just above sea level, and a good part of it sits below. Enormous pumps were a big part of the city’s $14.6 billion storm protection upgrade after Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005, and their struggles are a subject of citywide scrutiny every time it rains. Topographically, New Orleans is often likened to a bowl, but it’s more like a waffle, with pockets of low ground that fill up with just a few inches of rain.

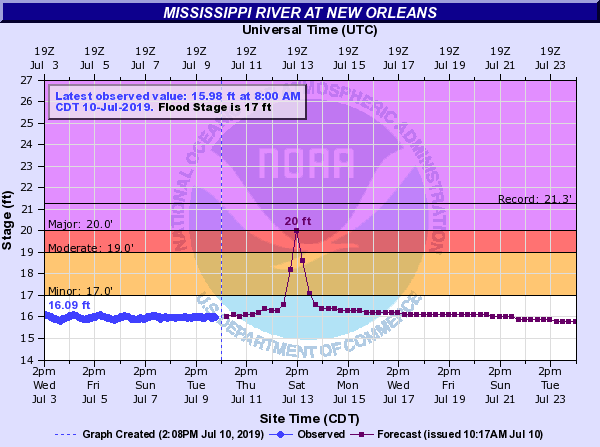

A rain forecast like Barry’s is never welcome news in New Orleans. But what makes this storm particularly ominous is that it comes at a time when the Mississippi River in New Orleans is just below flood stage, an unusual and unprecedented development this late in the year. As I wrote in June, the river—swollen by a record year of rainfall in the Midwest—has never been so high, so long. A few feet of rain and a mid-sized storm surge are projected to bring the river to a height it hasn’t hit in more than 90 years, reaching the top of the levees. Another foot would cause river water to crash into the neighborhoods below. Katrina hit when the river was running at 3 feet; it currently sits at 16 feet.

The levees top out around 20 feet; storm surge on the Mississippi is projected at 20 feet. If the forecast stands, at least some water will overtop the levees along the banks of the river.