By Janet Larsen and Savina Venkova

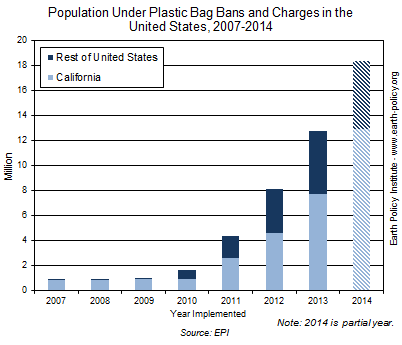

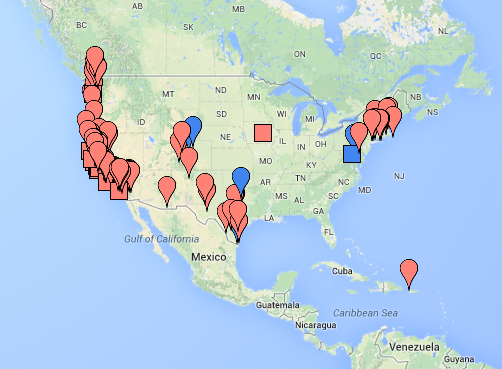

Los Angeles rang in the 2014 New Year with a ban on the distribution of plastic bags at the checkout counter of big retailers, making it the largest of the 132 cities and counties around the United States with anti-plastic bag legislation. And a movement that gained momentum in California is going national. More than 20 million Americans live in communities with plastic bag bans or fees. Currently 100 billion plastic bags pass through the hands of U.S. consumers every year—almost one bag per person each day. Laid end-to-end, they could circle the equator 1,330 times. But this number will soon fall as more communities, including large cities like New York and Chicago, look for ways to reduce the plastic litter that blights landscapes and clogs up sewers and streams.

While now ubiquitous, the plastic bag has a relatively short history. Invented in Sweden in 1962, the single-use plastic shopping bag was first popularized by Mobil Oil in the 1970s in an attempt to increase its market for polyethylene, a fossil-fuel-derived compound. Many American customers disliked the plastic bag when it was introduced in 1976, disgusted by the checkout clerks having to lick their fingers when pulling the bags from the rack and infuriated when a bag full of groceries would break or spill over. But retailers continued to push for plastic because it was cheaper and took up less space than paper, and now a generation of people can hardly conceive of shopping without being offered a plastic bag at the checkout counter.

The popularity of plastic grocery bags stems from their light weight and their perceived low cost, but it is these very qualities that make them unpleasant, difficult, and expensive to manage. Over one third of all plastic production is for packaging, designed for short-term use. Plastic bags are made from natural gas or petroleum that formed over millions of years, yet they are often used for mere minutes before being discarded to make their way to a dump or incinerator—if they don’t blow away and end up as litter first. The amount of energy required to make 12 plastic bags could drive a car for a mile.

In landfills and waterways, plastic is persistent, lasting for hundreds of years, breaking into smaller pieces and leaching out chemical components as it ages, but never fully disappearing. Animals that confuse plastic bags with food can end up entangled, injured, or dead. Recent studies have shown that plastic from discarded bags actually soaks up additional pollutants like pesticides and industrial waste that are in the ocean and delivers them in large doses to sea life. The harmful substances then can move up the food chain to the food people eat. Plastics and the various additives that they contain have been tied to a number of human health concerns, including disruption of the endocrine and reproductive systems, infertility, and a possible link to some cancers.

California—with its long coastline and abundant beaches where plastic trash is all too common—has been the epicenter of the U.S. movement against plastic bags. San Francisco was the first American city to regulate their use, starting with a ban on non-compostable plastic bags from large supermarkets and chain pharmacies in 2007. As part of its overall strategy to reach “zero waste” by 2020 (the city now diverts 80 percent of its trash to recyclers or composters instead of landfills), it extended the plastic bag ban to other stores and restaurants in 2012 and 2013. Recipients of recycled paper or compostable bags are charged at least 10ȼ, but—as is common in cities with plastic bag bans—bags for produce or other bulk items are still allowed at no cost. San Francisco also is one of a number of Californian cities banning the use of polystyrene (commonly referred to as Styrofoam) food containers, and it has gone a step further against disposable plastic packaging by banning sales of water in plastic bottles in city property.

All told, plastic bag bans cover one-third of California’s population. Plastic bag purchases by retailers have reportedly fallen from 107 million pounds in 2008 to 62 million pounds in 2012, and bag producers and plastics manufacturers have taken note. Most of the ordinances have faced lawsuits from plastics industry groups like the American Chemistry Council (ACC). Even though the laws have largely held up in the courts, the threat of legal action has deterred additional communities from taking action and delayed the process for others.

Ironically, were it not for the intervention of the plastics industry in the first place, California would likely have far fewer outright plastic bag bans. Instead, more communities might have opted for charging a fee per bag, but this option was prohibited as part of industry-supported state-wide legislation in 2006 requiring Californian grocery stores to institute plastic bag recycling programs. Since a first attempt in 2010, California has come close to introducing a statewide ban on plastic bags, but well-funded industry lobbyists have gotten in the way. A new bill will likely go up for a vote in 2014 with the support of the California Grocers Association as well as state senators who had opposed an earlier iteration.

Seattle’s story is similar. In 2008 the city council passed legislation requiring groceries, convenience stores, and pharmacies to charge 20ȼ for each one-time-use bag handed out at the cash register. A $1.4 million campaign headed by the ACC stopped the measure via a ballot initiative before it went into effect, and voters rejected the ordinance in August 2009. But the city did not give up. In 2012 it banned plastic bags and added a 5ȼ fee for paper bags. Attempts to gather signatures to repeal this have been unsuccessful. Eleven other Washington jurisdictions have also banned plastic bags, including the state capital, Olympia. (See database of U.S. plastic bag initiatives and a timeline history.)

A number of state governments have entertained proposals for anti-plastic bag legislation, but not one has successfully applied a statewide charge or banned the bags. Hawaii has a virtual state prohibition, as its four populated counties have gotten rid of plastic bags at grocery checkouts, with the last one beginning enforcement in July 2015. Florida, another state renowned for its beaches, legally preempts cities from enacting anti-bag legislation. The latest attempt to remove this barrier was scrapped in April 2014, although state lawmakers say they will revisit the proposal later in the year.

Opposition to plastic bags has emerged in Texas, despite the state accounting for 44 percent of the U.S. plastics market and serving as the home to several important bag manufacturers, including Superbag, one of America’s largest. Eight cities and towns in the state have active plastic bag bans, and others, like San Antonio, have considered jumping on the bandwagon. Austin banned plastic bags in 2013, hoping to reduce the more than $2,300 it was spending each day to deal with plastic bag trash and litter. The smaller cities of Fort Stockton and Kermit banned plastic bags in 2011 and 2013, respectively, after ranchers complained that cattle had died from ingesting them. Plastic bags have also been known to contaminate cotton fields, getting caught up in balers and harming the quality of the final product. Plastic pollution in the Trinity River Basin, which provides water to over half of all Texans, was a compelling reason for Dallas to pass a 5ȼ fee on plastic bags that will go into effect in 2015.

Washington, D.C., was the first U.S. city to require food and alcohol retailers to charge customers 5ȼ for each plastic or paper bag. Part of the revenue from this goes to the stores to help them with the costs of implementation, and part is designated for cleanup of the Anacostia River. Most D.C. shoppers now routinely bring their own reusable bags on outings; one survey found that 80 percent of consumers were using fewer bags and that over 90 percent of businesses viewed the law positively or neutrally.

Montgomery County in Maryland followed Washington’s example and passed a 5ȼ charge for bags in 2011. A recent study that compared shoppers in this county with those in neighboring Prince George’s County, where anti-bag legislation has not gone through, found that reusable bags were seven times more popular in Montgomery County stores. When bags became a product rather than a freebie, shoppers thought about whether the product was worth the extra nickel and quickly got into the habit of bringing their own bags.

One strategy of the plastics industry—concerned about declining demand for its products—is an attempt to change public perception of plastic bags by promoting recycling. Recycling, however, is also not a good long-term solution. The vast majority of plastic bags—97 percent or more in some locales—never make it that far. Even when users have good intentions, bags blow out of outdoor collection bins at grocery stores or off of recycling trucks. The bags that reach recycling facilities are the bane of the programs: when mixed in with other recyclables they jam and damage sorting machines, which are very costly to repair. In San Jose, California, where fewer than 4 percent of plastic bags are recycled, repairs to bag-jammed equipment cost the city about $1 million a year before the plastic bag ban went into effect in 2012.

Proposed plastic bag restrictions have been shelved in a number of jurisdictions, including New York City, Philadelphia, and Chicago, in favor of bag recycling programs. New York City may, however, move ahead with a bill proposed in March 2014 to place a city-wide 10ȼ fee on single-use bags. Chicago is weighing a plastic bag ban.

In their less than 60 years of existence, plastic bags have had far-reaching effects. Enforcing legislation to limit their use challenges the throwaway consumerism that has become pervasive in a world of artificially cheap energy. As U.S. natural gas production has surged and prices have fallen, the plastics industry is looking to ramp up domestic production. Yet using this fossil fuel endowment to make something so short-lived, which can blow away at the slightest breeze and pollutes indefinitely, is illogical—particularly when there is a ready alternative: the reusable bag.

A subsequent Earth Policy Institute release will cover international action on plastic bags. Additional information, including a timeline and table on selected plastic bag regulations in the United States, is available at www.earth-policy.org.