Alan Durning’s article makes a lot of good points about the need to do more than just improve the efficiency of our personal transport. It’s a great article, but it also contains a few inaccuracies that I feel obligated to clear up before the global warming deniers (among others) try to use them.

I can tell from the comments on Alan’s post that some readers are under the mistaken impression that his conclusions are a reflection of the EPRI/NRDC (PDF) report cited, but many are actually counter to that report. For example:

According to the most comprehensive study of the question yet completed, again by EPRI and NRDC, rapid adoption of plug-in hybrids between now and 2050 could — repeat, could— slash U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions

The report does not use the word “could.” The report says what plug-in hybrids “are” going to do (i.e., those already in existence “are” doing the following):

Researchers drew the following conclusions from the modeling exercises: Annual and cumulative GHG emissions “are” reduced significantly across each of the nine scenario combinations [my emphasis].

Also, on this:

For this auto (pictured in our back yard, with our Flexcar visible out front), I wondered, would my family give up its car-less ways? Would the joy of these 100+ mpg wheels cause us to end our 21 months of car-free-ness …

Alan’s definition of “car-free” and “car-less” is different than mine. Flexcar is essentially a sophisticated car rental system. People who lease or rent cars rather than buy them can hardly be called car-free or car-less. I have a friend who calls himself car-free. He not only does not own a car, he also refuses to get into one. He walks or uses mass transit and if he can’t get somewhere without them, he doesn’t go. It’s an ethical issue with him, and yes he is extreme. Now that is what I would call car-free.

Flexcar has advantages and disadvantages and works for some lifestyles but not for all. The major advantages are that it’s cheaper than car ownership for those who don’t drive much and more convenient than traditional car rental. On the other hand, it is way less convenient than having your own car if cost is not a big concern (and also I would guess, way less convenient than having to plug a car into a charger).

From a global warming perspective, the operation of a Flexcar has no advantage over a car driven by it’s owner (although sharing cars does mean less manufacturing). As far as day-to-day operation is concerned, all that matters in the end is how much gas you consume. Who actually owns the car consuming the gas is irrelevant. In a sense, anyone making a car payment does not actually own his or her car either. It is entirely possible that a family using Flexcar could produce more greenhouse gases than my family. We just don’t drive much and the car we drive the most is averaging almost twice the Flexcar fleet average for MPG.

Without fixing the laws — and specifically, without a legal cap on greenhouse gases — plug-ins could actually do more harm than good … and notwithstanding any future greenhouse-gas benefits — driving a plug-in hybrid right now in North America probably increases climate-warming emissions, compared with driving a regular hybrid.

This conclusion serves Alan’s point, but it is also a conclusion that is counter to the report cited. The only way operating plug-ins could actually produce more greenhouse gases would be for our grid to suddenly reverse the decades long trend of getting cleaner and more efficient. If that happens, from a greenhouse gas perspective, it won’t matter what kind of car you drive or if you drive at all.

Why? In a nutshell, because most of a plug-in’s electricity comes from coal-fired power plants.

Technically, yes, 56 percent comes from coal. But that means 44 percent does not. What matters is the grid average, as these calculations demonstrate:

- Today’s grid average is 1.3 pounds of CO2 produced per Kilowatt.

- A Prius consumes about 250 Watt-hours per mile on electric.

- The average car today produces about 12,000 pounds CO2 and moves about 12,000 miles annually.

- A Prius produces about 6000 pounds CO2 annually if driven the same miles.

1.3 x 0.250 x 12,000 miles = 3,900 pounds CO2 (all miles electric)

(1.3 x 0.250 x 6,000 miles) + (6,000 pounds x 1/2) = 4,950 pounds CO2 (1/2 of miles electric)

(1.3 x 0.250 x 3,000 miles) + (6,000 pounds x 3/4) = 5,475 pounds CO2 (1/4 of miles electric)

Now, if we are successful (because if we aren’t we’re toast) reducing that 1.3 average to say, 0.6, you can see the multiplier effect. Driving 1/4 of your plug-in hybrid car miles on electric would produce about 2700 pounds instead of today’s Prius average of 6000.

And without the second two fixes — working technology and competitive prices — plug-ins won’t spread beyond the Hollywood set

Substitute the word “Prius” for the term “plug-in” and see how that sentence reads.

Apparently, you can get such features on most new cars. (Being car-less, I had no idea!)

Never mind that the Flexcars are mostly new, calling someone car-free just because they rent or lease a car instead of make payments on one strikes me as being a bit of a stretch.

You see, every watt of hydro and wind electricity that we produce is already spoken for, used to satisfy demand somewhere here or elsewhere in the western power grid.

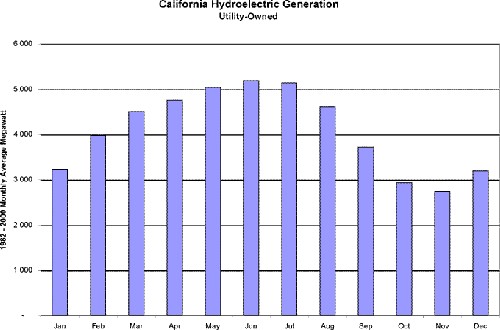

If that were so the bars on the following chart would all be the same length:

So consuming local power (usually, hydropower) to charge plug-ins means that, somewhere else on the grid, another coal-fired plant has to rev up just a bit to replace the power sucked down by the car’s batteries.

Just a bit, but not enough to nullify the benefits of the plug-in; remember, 56 percent coal, 44 percent other.

Until renewable power becomes so abundant that we get virtually none of our power from dirty coal plants — until we have long periods of each day when we have no other use for some of our wind and solar and hydro power — any marginal demand for baseline power (the night-time power that can recharge plug-in hybrids) will most likely be met by increased generation from coal.

All reports I have seen, including the one cited by Alan here, disagree with Alan’s above conclusion. Although it is true that more coal will be burned it will not be enough to offset the greenhouse advantages of plug-in cars.

Trading gasoline for coal-fired power is a bad deal for the climate.

That is a straw-man argument. Plug-in hybrids won’t be doing that. Even today they will be trading gasoline for the average of 56 percent coal, 44 percent non-coal.

This chart adapted from the EPRI/NRDC report illustrates the situation. The chart shows that, if the electricity that charges a plug-in’s batteries comes exclusively from coal, the total climate-disrupting emissions per mile from a plug-in exceed the emissions from a regular hybrid.

First, note that this chart does not exist in the report. It was adapted (created by the author) from the charts in the report and presents a skewed, out of context perspective. Go to the report and look at their actual charts and you will see what I mean. Plug-ins win in every category except the fictional one of a world where we get all of our electricity from coal.

Next, understand that nobody (but Alan apparently) thinks we will transition to a grid that produces more CO2 than today. And finally, note that Alan only compares the plug-in hybrid to regular hybrids. Even so, plug-in hybrids running on pure coal (which is a ridiculous assumption) would dwarf conventional cars with respect to greenhouse gases, local emissions, and fuel costs.

Even though today’s power grid doesn’t make plug-ins a good deal for the climate, EPRI and NRDC find that replacing gasoline and diesel vehicles with electric ones will eventually be a climate plus — assuming the electric power system gets cleaner over time. But that’s a big assumption. The only guarantee of clean plug-ins (like those shown in the shortest bars of the chart) would be a firm, descending legal limit on greenhouse-gas emissions.

No. None of the above is accurate. That is not what the report says. The report says that every plug-in hybrid that hits the road from today on will produce far fewer greenhouse gases even with today’s mix of power generation.

So in essence, the real barrier to reducing vehicle emissions isn’t car technology at all. It’s the law.

No. My Prius gets twice the national average. It has cut my fuel use in half with pure technology and no changes in laws and it isn’t even a plug-in.

Until then, plug-ins will likely be slightly worse for climate than regular hybrids.

No. Every report I have read, including the one he references, says otherwise.

Even the best batteries are limited in range, lifetime, and recharge speed … the storage capacity of batteries shrinks over time, and may eventually require costly replacements. In contrast, recharging your state-of-the-art lithium-ion battery with 20 miles’ worth of electricity takes hours, maybe even all night … The all-electric Tesla sports car’s half-ton battery system alone costs almost as much as a new Prius …

No. Prius batteries last the life of the car. A plug-in hybrid has the same range as any other car, it just isn’t all done on electric. Recharge speed is irrelevant on a plug-in hybrid because it will tool around on gas until it can recharge. Not to mention, rate of charge, especially for the A123 battery is a function of how much current your charger puts out. My A123 batteries charge in about 30 minutes.

battery costs need to come down by about 60 percent for plug-in technology to compete in the market.

Time will tell. This blindingly fast computer I’m typing on has 80 GB of hard drive and only cost $600 compared to my first computer — which cost $1,200, had 3.2 GB of hard drive and came to a standstill when you tried to run more than two apps at a time. And then there was my first digital camera. Four hundred dollars got me 15 crappy-resolution photos and I burned through four batteries to get them. Today I take moving video on my cell phone that I got for free. What are the odds that battery costs will drop (lithium is not in short supply like nickel)?

In 1999, at the height of the fuel-cell craze, I remember listening to car makers and science writers foretelling the imminent arrival of the hydrogen economy. Soon thereafter, hype turned to disillusionment. More recently, biofuels have followed a similar trajectory, in which expectations blossomed far faster than actual market presence and, when unrealistic expectations were not met, the popular sentiment began to switch to rejection. Plug-in hybrids are becoming the new “it” technology in Cascadia, and I worry they’ll fall from favor as quickly as their predecessors.

I like to use that hydrogen economy analogy myself to critique biofuels. It doesn’t work when using it to describe the hybrid car fleet, which saves more gas annually than all the corn ethanol produced in 2001.

… every new fuel or power train design leads to a whirlwind romance, followed, eventually, by disenchantment.

I don’t know a whole lot of people driving Priuses who are disenchanted with them. We are averaging just over 50 MPG.

And the drama distracts from less glamorous but ultimately more effective, political and institutional solutions, such as auctioned cap-and-trade systems, carbon taxes …

The drama does not distract from anything. If anything, these ideas, like the Prius, are motivating and exciting people. The goal of cap-and-trade and carbon taxes is to motivate efficiency though better practices and better technology. Given time, as happened with the hydrogen idea (and hopefully for biofuels), reality can float to the surface. This post critiquing your post is part of that process.

When we make these changes collectively, through our democratic institutions, vehicle technology will take care of itself. Investors will finance new product development. Consumers will select those products that meet their needs at a price they’re willing to pay

I could not agree more with the above statement.