In his 1996 book Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom, the great food anthropologist Sidney Mintz concluded that the United States had no cuisine. Interestingly, Mintz’s definition of cuisine came down to conversation. For Mintz, Americans just didn’t engage in passionate talk about food. Unlike the southwest French and their cassoulet, most Americans don’t obsess and quarrel about what comprises, say, an authentic veggie burger.

But if cuisine comes down to talk, things are looking up a decade after Mintz cast his judgment. Now, more and more people are buzzing about food: not only about what’s good to eat, but also — appropriately for the land that invented McDonald’s and Cheetos — about what’s in our food, where it came from, how it was grown.

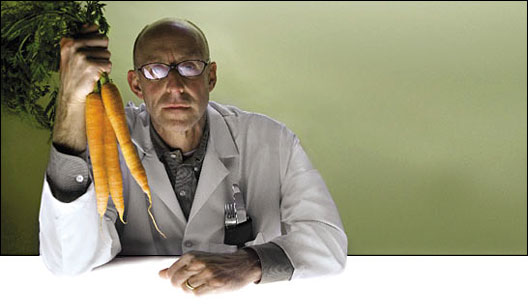

No writer has galvanized this new national conversation on food more than Michael Pollan, from his muckraking articles on the meat industry for The New York Times Magazine earlier this decade to the publication last year of The Omnivore’s Dilemma. On a recent day when he was reviewing the galleys of his latest book, due out in January, I rang up Pollan at his Berkeley, Calif., home to talk … about food.

So tell me a little bit about what you’ve been working on recently.

The new book is called In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto. It’s a book that really grew out of questions I heard from readers after Omnivore’s Dilemma, which was basically so how do you apply all this? Now that you’ve looked into the heart of the food system and been into the belly of the beast, how should I eat, and what should I buy, and if I’m concerned about health, what should I be eating? I decided I would see what kind of very practical answers I could give people.

In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto, by Michael Pollan.

I spent a lot of time looking at the science of nutrition, and learned pretty quickly there’s less there than meets the eye, and that the scientists really haven’t figured out that much about food. Letting them tell us how to eat is probably not a very good idea, and indeed the culture — which is to say tradition and our ancestors — has more to teach us about how to eat well than science does. That was kind of surprising to me.

It really comes down to seven words: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” What is food? How do you know whether you’re getting food or a food-like product? The interesting thing that I learned was that if you’re really concerned about your health, the best decisions for your health turn out to be the best decisions for the farmer and the best decisions for the environment — and that there is no contradiction there.

The other thing that’s interesting, along the same lines, is this idea in American culture that what is good for you tastes bad, and what tastes bad is good for you.

Yes, exactly right. There’s no sacrifice in eating well, there is no sacrifice in pleasure. To the contrary, the best-grown food is actually the tastiest. Now, it wasn’t always true. I mean, you know, in the first generation of organic farmers, they weren’t that good at it. But the quality has dramatically improved and is superb right now.

Then there’s this idea that food is something you can endlessly fragment: if you find something in a food that’s beneficial, you can isolate it, and concentrate it, and put it in a pill.

It’s the reductionist’s logic of food science, basically. And the interesting thing is that whenever that has been tried, it has failed. Foods are much more than the sum of their nutrient parts, and you cannot expect to get the same effect. Now there are things like vitamins that have been isolated, and in their isolated form they can cure deficiency diseases. But when they’ve tried to take out the antioxidants, things like beta-carotene and vitamin E, they don’t seem to work.

There’s an analogy there with agriculture: the macronutrients in food and the macronutrients in soil. A, B, C, and D vs. N, P, and K. Turns out that soil needs more than just isolated N, P, and K to produce fully nutritious food.

There’s a mystery at both ends of the food chain. There’s the mystery about what makes a healthy soil, which you cannot yet fake or simulate, and there’s the mystery of what makes a healthy food, which you cannot yet simulate or fake.

The advice to “eat food, not much, mostly plants” is deceptively simple — how do you apply that in a society that’s become addicted to convenience food?

I think that there’s some brainwashing going on with this idea that we don’t have time to cook anymore. We have made cooking seem much more complicated than it is, and part of that comes from watching cooking shows on television — we’ve turned cooking into a spectator sport. We’re terrified to play tackle football too when we watch how it’s played on TV — we’d get killed. But cooking’s a whole lot easier than it appears on Iron Chef.

We cook every night here. My wife and I both work, and we can get a very nice dinner on the table in a half hour. It would not take any less time for us to drive to a fast-food outlet and order, sit down, and bus our table. [But] when you create this image of people as being hurried, and harried, and of course you need TV dinners, that kind of sinks in. They kind of flatter us by telling us we’re too busy and that we have such rushed lives, but in the end we find time for what matters. In just the last 10 years we’ve found, what, two or three hours a day to deal with the internet? It’s a matter of priority, it’s not really about ability. Some people are very intimidated about cooking and I think that’s a shame, and I think we have to help people get over that by teaching them how to cook, teaching kids how to cook in school.

How did you learn to cook?

I learned to some extent from my mother, who was a really good cook, just hanging out in the kitchen watching her do it. I [had] a classic suburban childhood on Long Island. My mom cooked dinner four or five nights a week, and always your classic — there was some kind of protein, and two vegetables, and dessert, the whole bit. And it was a really important part of our family life. When I was living alone in my 20s, when I got my first apartment, I cooked partly because I couldn’t afford to go out — you know, it’s kind of a myth that it’s more expensive to cook. So I’ve always been kind of interested in it.

There are times where you fall out of the habit and you get seduced by alternatives and it seems harder than it really is. But you know, as I started shopping at farmers’ markets and joined a CSA — that pushes you back to the kitchen. That’s one of the unintended consequences of buying food that way: you can’t find anything microwaveable at the farmers’ market, so you begin cooking again.

I’ve lived in places where I could walk five minutes to an incredible farmers’ market. There are a lot of people who don’t have that privilege in other parts of the country. But I think that is changing, and there’s a lot of great programs going on.

I spent a lot of time on the road last year, and I was surprised at where the local food movement was taking root. It was a lot of places that you wouldn’t expect it. And I know that there are still food deserts — ironically they tend to be in the farm belt, a lot of them.

One of the things I always have to be aware of is I live in a place where it’s very easy to eat off the supermarket grid, if you will. My farmers’ market is open 50 weeks a year, and the CSA runs, I think, 48 weeks a year — and that’s only because they need a break. But I do think that to the extent there are alternatives and people support them, even if they’re small now, they will very quickly get much bigger.

Omnivore’s Dilemma clearly struck a nerve. Were you surprised by the reaction, and did it start the conversation you were hoping it would?

I was completely flabbergasted by the reaction. I had no idea it would start a conversation to the extent it has. You work on a book for years, and you don’t know where the culture’s going to be when you finish. And sometimes the message you’re bringing happens to coincide with other things going on in the culture, and I think that that’s what happened. There were several other very good food books out, and they all did quite well. So I think there was something in the air, and people were receptive to the message.

I was very struck by the energy I felt in audiences and still feel in audiences, which is very much a political energy. At a time when people feel really frustrated about electoral politics, very frustrated about the war, this administration in lots of ways, I think that that’s part of what is creating this center of gravity around food. Because it’s really fundamental politics, because — and I think that you’ve heard me say this — you have a power here that you don’t have elsewhere. You’ve got three votes a day, and how you cast those votes, we have seen over the last few years, has a tremendous effect.

The most gratifying thing I hear is farmers, ranchers, who say they’re having a great year this year and more people are coming in and asking for pastured livestock, more people are joining CSAs … consumers are starting to reconceive what it means to be a consumer, and [see] that citizenship is part of consumption. … People are getting something besides food when they go to the farmers’ market, they’re getting a sense of community.

When you really get into local food, it’s suddenly about community, coming together — at the farmers’ market, meeting a farmer at the CSA, cooking with your friends and family. Seems like there’s a hunger for these things in a post-modern society that’s built on suburbia, and the car, and atomization.

You know, people have looked to food for all these values for thousands of years — food was a way to come together, it was a way to express your identity, it was a way to engage with nature — food has always had this power. And I think we’ve had a kind of temporary forgetting of that, and this idea that food is just fuel, food is about health or illness, these very simplistic, reductive ideas have kind of thinned out the whole experience. But there’s a desire to thicken it again, and lo and behold food is providing all these satisfactions that people were missing.

Both of us have been active in the effort to demystify the farm bill and convince people to care about it. What are your hopes for the farm bill at this point?

I was just on the phone this morning with a congressman (and by the way, they’re calling me, I’m not calling them at this point, and I think that’s interesting). There’s more politics around the farm bill — more grassroots politics, more reform politics — than there has been in a generation. At the same time, and as a result of that, there has been a defensive reaction that has been fierce. And there is a resentment that anyone from the outside — which is to say outside of these commodity crops, outside of the memberships of these committees — is trying to get in on the issue and get in on the debate. There was a very telling quote in the San Francisco Chronicle by [Rep.] Collin Peterson [D-Minn.] … where he says, “These city people don’t know what they’re talking about, they should stay out of it.”

I think they understand as soon as they start negotiating these large questions then everyone’s going to pile in and we’re going to get a very different kind of farm bill, and they just don’t want this to happen. And when I say “they,” I’m talking about the Midwestern congressmen and senators on both agriculture committees.

Now it may be that the reformers have not done a good enough job of framing proposals in a way that doesn’t look threatening. I think the basic tack has been a very simple anti-subsidy tack: “Subsidies are welfare, farmers should fend for themselves when prices are good.” So it looks like you’re simply trying to take something away from farmers, and I think politically perhaps that has contributed to the powerful reaction we’ve seen … I don’t know how to craft those proposals, I’m not a policymaker, but I think we’ve made a mistake by equating reform with the destruction of farm support.

We’ll have to see what happens, but it’s not time to give up on this. I detect an enormous amount of anxiety about the politics on the part of the committees, and a sense that other people in Congress are looking now over the shoulder of the ag committee in a way they haven’t before. So defensiveness — you know, this is defensiveness, this isn’t just power, and people should realize that.

I was wondering if you’d been back to Iowa since you did your research on Omnivore’s Dilemma. When you were there corn was $1.50 a bushel, and now it’s $4 a bushel.

I know, the good times are rolling right now. I have not. I’m going to go back this winter, though. The book tour is going to take me to Iowa City, which I’m really looking forward to. Not that that’s exactly corn country, but it’s close.

I’ve done a lot of radio in the Corn Belt, and it’s clear that I’ve pissed off some people there. And I spoke at Iowa State and a group of people got up and walked out because I was taking the name of corn in vain.

Since Omnivore’s Dilemma came out, John Mackey publicly criticized you, and at the same time he started rolling out these local foods measures, and now when you walk into a Whole Foods you see “Buy Local” signs everywhere. What is your take on Whole Foods’ Buy Local effort so far?

The Berkeley face-off.

It was a very interesting exchange with him. It unfolded over the course of several months in these letters, and then he came to Berkeley to have an onstage conversation with me, which was surprising and somewhat courageous of him, given Berkeley’s attitude toward Whole Foods. And in many ways it was a very productive exchange: I learned something about how that company works, and he made some very promising initiatives.

I have seen what you’ve seen when I go around the country visiting Whole Foods. There’s a much greater emphasis on local food in the signage and on the shelf. But I haven’t done the kind of systematic look — and it needs to be done about now — to see how far they have come. It’s not for me to do; I would feel a little awkward doing it myself. But I’m hoping that other journalists will do it.

Well, I know you’ve got to wrap up. I’ve had a great time talking to you.

Yeah, me too. It’s always great to talk about this stuff — it’s just great that you’re out there doing this, and that you bring this perspective as a farmer is very powerful. I’ve really enjoyed your stuff, and it’s been wonderful to see the publicity you’ve gotten this year. I saw that terrific piece in Gourmet.

Oh, speaking of that, that article in Gourmet exposed my predilection for chips. And my editor wanted me to ask you: What is your junk-food weakness?

Oh, god, let me think … My favorite packaged junk food has always been Cracker Jacks. Which is, of course, a corn product of a kind. Of several kinds. It’s popcorn coated in corn syrup.

I haven’t had those in years, but I loved them as a kid.

Cracker Jacks are great. Although the prizes have gone way downhill.