Climate change is a fact, and it is almost entirely made by man. It is jointly responsible for the rise in severe weather-related natural disasters, since the weather machine is “running in top gear”. The figures speak for themselves: according to data gathered by Munich Re, weather-related natural catastrophes have produced US$ 1,600bn in total losses since 1980, and climate change is definitely a significant contributing factor. We assume that the annual loss amount attributable to climate change is already in the low double-digit billion euro range. And the figure is bound to rise dramatically in future.

Those are the words of the CEO of Munich Re, the world’s largest reinsurer, in December. The anti-science crowd tries to shout down any talk of a link between climate change and extreme weather but even the loudest shouter told the journal Nature back in 2006, “Clearly since 1970 climate change (i.e., defined as by the IPCC to include all sources of change) has shaped the disaster loss record.” Indeed, that Nature article reported four years ago:

At a recent meeting of climate and insurance experts, delegates reached a cautious consensus: climate change is helping to drive the upward trend in catastrophes.

The evidence has only gotten stronger in recent years. A major study published in 2009, “Tropical cyclone losses in the USA and the impact of climate change — A trend analysis based on data from a new approach to adjusting storm losses” concluded:

In the period 1971–2005, since the beginning of a trend towards increased intense cyclone activity, losses excluding socio-economic effects show an annual increase of 4% per annum. This increase must therefore be at least due to the impact of natural climate variability but,more likely than not, also due to anthropogenic forcings.

A 2009 NOAA-led report, Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States, identified a number of climate-related impacts that are occurring now and expected to increase in the future that could shape the disaster loss record:

Many phony charges are now being leveled at the IPCC because the anti-science crowd smells blood in the water, and many “journalists” are ready to repeat their nonsense (see “EXCLUSIVE: UN scientist refutes Daily Mail claim he said Himalayan glacier error was politically motivated.”

The newest phony charge came Sunday from another dubious source in the British press, “UN wrongly linked global warming to natural disasters.” But on Monday, the IPCC slammed the story as “misleading and baseless.” As the “IPCC statement on trends in disaster losses” explains:

The Sunday Times article gets the story wrong on two key points. The first is that it incorrectly assumes that a brief section on trends in economic losses from climate-related disasters is everything the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (2007) has to say about changes in extremes and disasters. In fact, the Fourth Assessment Report reaches many important conclusions, at many locations in the report, about the role of climate change in extreme events. The assessment addresses both observations of past changes and projections of future changes in sectors ranging from heat waves and precipitation to wildfires. Each of these is a careful assessment of the available evidence, with a thorough consideration of the confidence with which each conclusion can be drawn.

The second problem with the article in the Sunday Times is its baseless attack on the section of the report on trends in economic losses from disasters. This section of the IPCC report is a balanced treatment of a complicated and important issue. It clearly makes the point that one study detected an increase in economic losses, corrected for values at risk, but that other studies have not detected such a trend. The tone is balanced, and the section contains many important qualifiers. In writing, reviewing, and editing this section, IPCC procedures were carefully followed to produce the policy-relevant assessment that is the IPCC mandate.

Kudos to the IPCC for responding to a trumped up charged quickly for once!

Coincidentally, I already had a guest post in the works from one of the country’s leading experts on the connection between climate change and extreme weather and the impact on the insurance industry, Evan Mills. So, the rest of this post is Mills, a scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, whom I have known for almost two decades. He is a true polymath (see “Building Commissioning: The Stealth Energy Efficiency Strategy“).

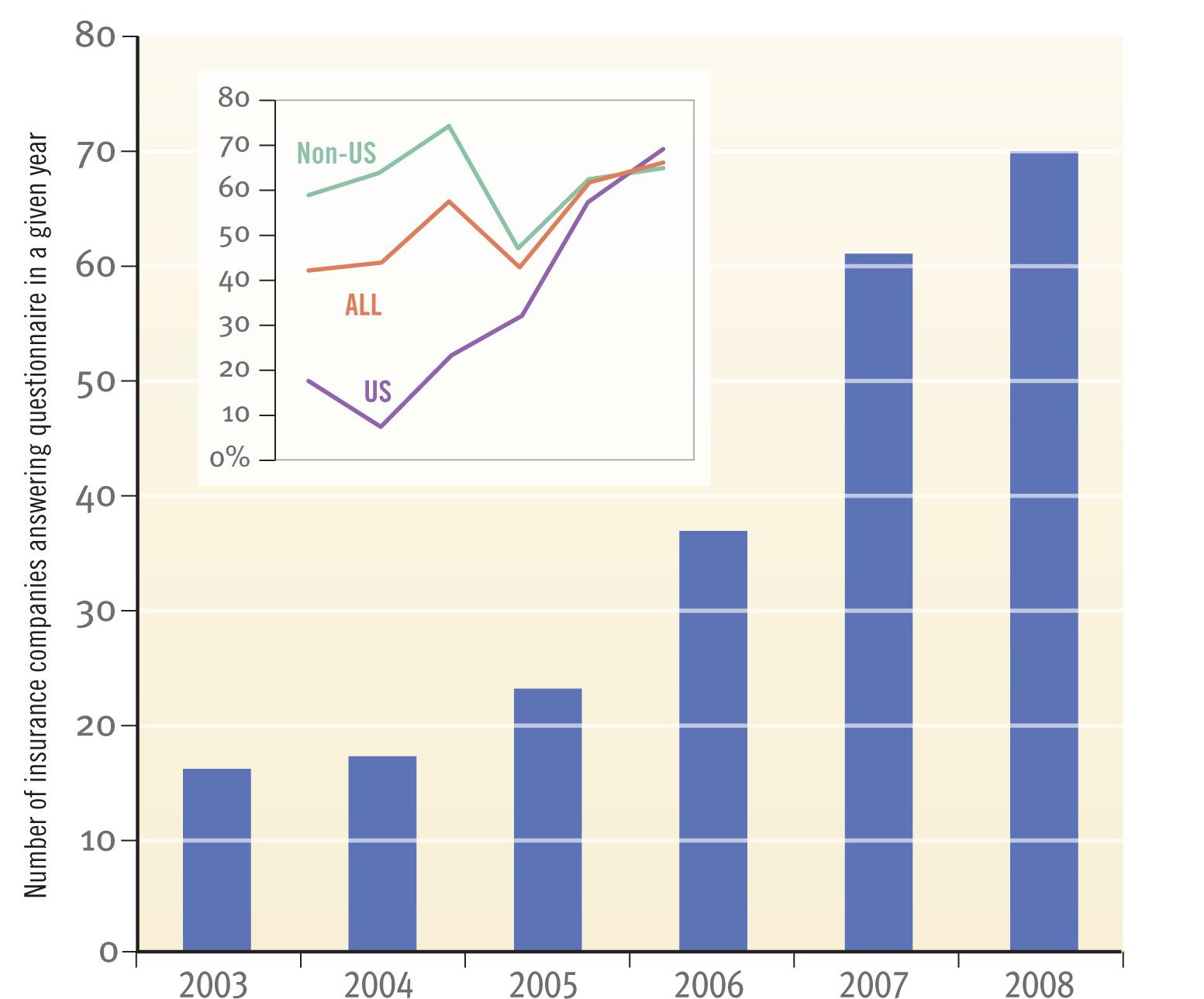

Chart: Climate-risk disclosure trends among U.S.- and non-U.S.-based insurance companies (Source: CDP data per Mills 2009)

I had the pleasure of keynoting a meeting on climate cha

nge convened last month in San Francisco by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), the American Insurance Association (AIA), the Reinsurance Association of America (RAA), and Ceres. The speaker line-up included Fireman’s Fund, Prudential Capital Group, Deutsche Asset Management, CalPERS, Willis Re, Zurich Financial Services,Wells Fargo, NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center, NRDC, the California Department of Insurance, and several catastrophe modeling and environmental consultants. All spoke in unison about the risks and opportunities of climate change and the role that insurers and their regulators are increasingly playing in responding to it.I argued in my presentation that climate change is the single greatest risk facing the insurance industry. Ernst & Young’s survey of 70 industry analysts seems to agree with me. As I’ve explained in Science, climate change is a systemicrisk not unlike the banking crisis that blindsided almost everyone thanks in no small part to a nasty coctail of undisclosed risks and wishful thinking. Astute insurers recognize a panoply of potential correlated losses triggered by climate change spanning the core business of underwriting (in almost every line of business, from property to life/health to liability), coupled with exposures through the assets in which they invest, topped off with with formidable collatoral reputational, regulatory, and competitive risks. A vanguard of insurers are responding with new products, services, and constructive engagement in public policy.

I also pointed out that insurer shareholders have emerged in force, most notably through the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), with members representing $55 trillion under management. Now, U.S. insurance regulators are asking insurers to proactively disclose their climate-risk assessment for the benefit of shareholders, customers, and, yes, even the insurers themselves.

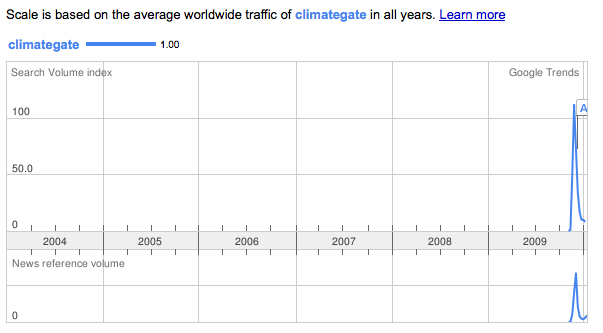

During the Q&A period, Robert Detlefsen, from the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies (NAMIC), asked to share a “comment” (which he emphasized was not a question) about my presentation. Detlefsen–formerly with Citizens for a Sound Economy and the Competitive Enterprise Institute–was displeased that I had not given more attention to the infamous CRU emails. I responded that I would be delighted to discuss the subject with him at length after the session. He elected not to take me up on this offer.

Pseudoscience appears to be more compelling to some than fact-based science or the pursuit of genuine understanding. Insurance based on pseudoscience risks deteriorating into pseudoinsurance.

A peculiar article by Evan Lehmann in the New York Times dredges up the stale CRU story (which has otherwise fizzled for lack of substance) and features Detlefsen’s distrust of science and distaste for climate risk disclosure, as summarized in a letter to his members’ regulators reiterating his concerns.

To the uninitiated reader, Lehmann’s piece might suggest that the entire insurance industry is questioning the veracity of climate science or the value of risk disclosure. What readers are left on their own to discover is that NAMIC–the trade organization featured as skeptical on climate change–“represents” but one branch of the industry (the mutual insurers). Two other insurance trade associations (AIA and RAA) not only co-hosted the summit but were actually on stage that day advancing a constructive discussion about how to get in front of the problem. Readers would also not have suspected that Detlefsen’s own organization sends a very different message through its excellent web portal on climate and insurance. Ironically, the insurance trade press has thus far given far more balanced treatment to these issues.

While Detlefsen characterizes the motivation of others in seeking climate-risk disclosure to regulators, shareholders, and customers as having “nakedly ideological ends,” over 100 insurance companies (approaching 70% of those asked) have somehow seen their way to replying to a voluntary climate risk disclosure process that has been conducted for years through CDP. They frequently find that the very process of assembling climate-disclosure documentation is constructive (not just a compliance exercise) and helps them think through the issues and better assess their risk and their progress towards managing that risk. Other U.S. insurance trade organizations have worked collaboratively to help craft the U.S. disclosure process. One of them, the American Insurance Association, is noted as being far more at peace with the regulators’ climate disclosure efforts than is NAMIC. Any observer would have to read quite a lot between the lines to support Detelfsen’s stipulation that that the regulators have any pre-determined expectations about the conclusions that insurers’ will reach through the disclosure process.

Climate skepticism among insurance trade associations like NAMIC is a more or less uniquely American phenomenon. Even then, some of NAMICs largest members—including household names like State Farm, Nationwide and Liberty Mutual —have been accepting of the science and very proactive in identifying responses to climate-change risks. To my knowledge, none have retracted their previous statements based on the stolen emails.

Other U.S. insurance tradegroups do not share Detlefsen’s perspective. The Reinsurance Association of America engaged in the climate discussion 15 years ago, and recently issued a constructive and proactive climate change policy statement. The American Insurance Association has also been engaged for over a decade, including participation in in

ternational fora. The Association of Bermuda Insurers and Reinsurers issued a policy statement just before the Copenhagen meeting. These trade associations seem to believe that it is not only appropriate but also beneficial for themselves and the companies they represent to engage.Although invoked by Detlefsen as a reason to scuttle the disclosure process, the “tempest in a thimble” brought on by the stolen emails has been debunked ad nauseum, including in a systematic third-party review by the Associated Press. [I cite the AP review only for those readers who don’t want to trust the scientific establishment for policing itself and reviewing the CRU issue formally.] Any substance that may remain does not change our fundamental scientific understanding of climate change. What Detlefsen desribes in his letter as my “intolerance for dissent” in finding no smoking gun in these emails, is more accurately characterized as my desire (and responsibility as a practicing scientist) to keep science fact-based. The factual inaccuracies that underpin the critics’ interpretation of these emails suggest either a very human tendancy to explain away bad news, profound technical incompetence, or sheer desperation in trying to delay addressing the risks. The interests of society (including those of insurers) are poorly served by sensationalized (and often non-fact-checked) reporting on peer-reviewed science. I would only add that questioning the findings of climate science based on non-expert interpretations of these emails is tantamount to discarding the very practice of scientific inquiry, while dismissing the judgment of hundreds of governments, business groups, and religious organizations that have scrutinized and accepted what mainstream science (and the Nobel Prize committee) has concluded about climate change since inquiry began over a century ago. From the Pentagon to the Supreme Court to the Vatican – human-induced climate change is accepted fact. This leaves precious little for holdouts to hang their hats on.

Chart: Climategate plot from Google/trends (Source: http://www.google.com/trends)

Many insurance companies can’t be bothered with foot-dragging. Through 2008, wedocumented nearly 643 specific activities on the part of 246 insurance entities from 29 countries (as well as 34 non-insurer collaborators). This represented a 50% year-over-year increase in the level of activity compared to that observed through 2007. These entities collectively earned $1.2 trillion in annual premiums that year (more than a quarter of the global total) and had $13 trillion in assets, while employing 2.2 million people.

Exasperated with the outcome in Copenhagen last month, the CEO of Munich Re (the world’s largest and most science-focused reinsurer) stated that:

“Climate change is a fact, and it is almost entirely made by man. It is jointly responsible for the rise in severe weather-related natural disasters, since the weather machine is “running in top gear”. The figures speak for themselves: according to data gathered by Munich Re, weather-related natural catastrophes have produced US$ 1,600bn in total losses since 1980, and climate change is definitely a significant contributing factor. We assume that the annual loss amount attributable to climate change is already in the low double-digit billion euro range. And the figure is bound to rise dramatically in future.”

To probe the internal consistency of Detlefsen’s hypothesis for a moment, even if climate change may not be happening, isn’t risk a product of uncertainty, and don’t insurers repeatedly tell us that “risk is our business”? And doesn’t selectively feeding on newspaper soundbites instead of thousands of peer-reviewed technical articles for climate intelligence invite myopia and risks of its own? Regulators—and insurance customers—expect a far higher level of due diligence. This is summed up well in a leading actuarial journal by the former corporate actuary and vice president of risk management for Nationwide Insurance — one of NAMIC’s largest members — and current chair of the Casualty Actuarial Society’s Climate Change Committee:

“For anyone attempting to move through the informational confusion on climate-change issues, the proliferation of counterfactual information makes the task daunting. Though the vast majority of climatologists support the global-warming theory, much of the media coverage gives approximately equal weight to the proponents of each side of the debate. … We need to recognize the likelihood that some climate changes are probable rather than improbable.”

Pretzel logic aside, foreword-looking insurers are adapting to a host of risks and opportunities. Technology and business practices are changing as fast as fast as the climate itself. This is already reshaping the demand for insurance. New risks will arise, e.g. those associated with carbon capture and storage, a revival of nuclear power, and geoengineering. Insurers that ignore this transition do so at their peril.