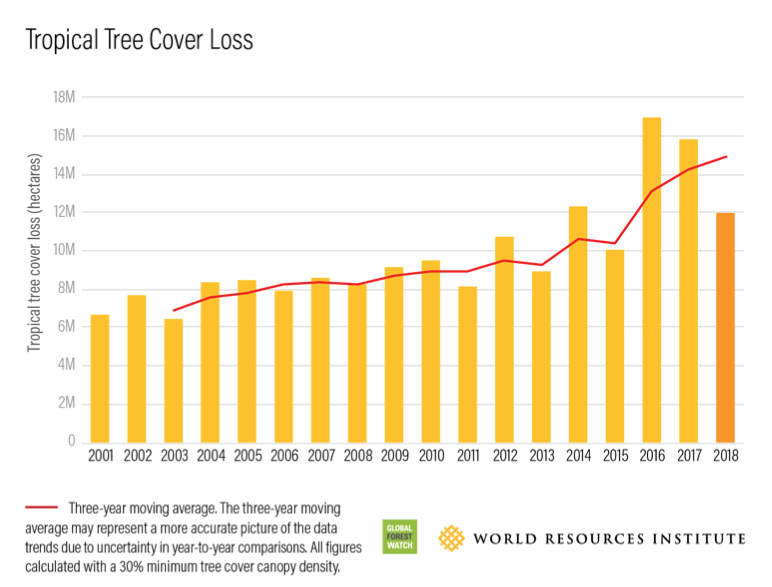

Every half hour, the world lost a football-field chunk of tropical forest in 2018.

Over the course of the year, that added up to a total forest loss of nearly 30 million acres, an area the size of Pennsylvania, according to the World Resources Institute’s annual report, out Thursday. As bad as that sounds, many more acres were lost in each of the two previous years, when huge fires wiped out millions of trees. The report is hardly cause for celebration, said Frances Seymour, senior fellow at WRI.

“The world’s forests are in the emergency room, said Seymour. “Even though they are recovering from extensive burns suffered in recent fires, the patient is also bleeding profusely from fresh wounds.”

Global Forest Watch

Deforestation is responsible for about 10 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. If deforestation were a country, it would be the third largest source of carbon pollution, after the United States and China.

“Tropical forest loss pulls the rug out from under efforts to stabilize the global climate,” Seymour said.

Every year, WRI’s Global Forest Watch pores over satellite images of the world’s woodlands and reams of data to monitor where trees are falling. Here are a few bullet points from the report:

Old growth deforestation continues: Primary or old-growth rainforest stores a lot of carbon in big trees and a lot of biodiversity — the frogs, bromeliads, lichens, leafcutter ants, and lemurs that live in those big trees. Since 2000, we’ve been losing about the same amount of primary rainforest every year: A Belgium-sized 9 million acres.

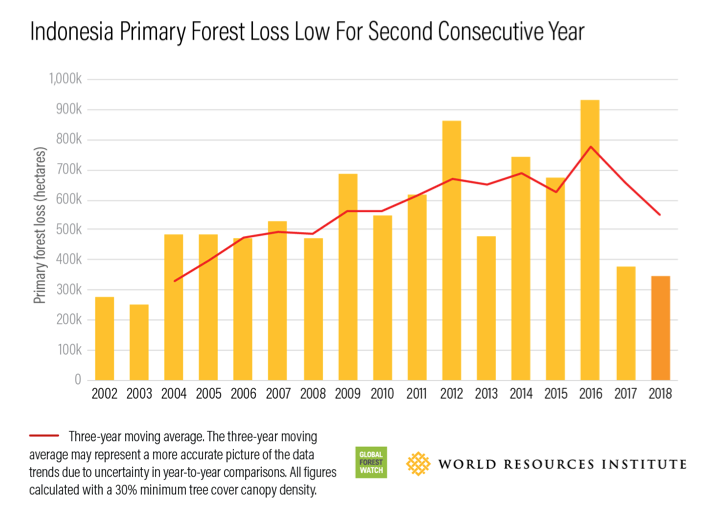

And it’s spreading: Efforts in Indonesia and Brazil to stem the loss of old-growth forests have started to work. By enforcing a moratorium on clearing primary forest, Indonesia has managed to bring deforestation down to the lowest level since 2003, said Belinda Margono from Indonesia’s Department of Environment and Forestry. But forests are falling at a quicker pace in West Africa, Colombia, Bolivia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Big trouble in Madagascar: The East Africane East African island island country lost a full 2 percent of its primary forest, more than any other country.

Peace brings cattle to Colombia: A truce between the government and between the government and rebels made it safe for farmers to enter previously perilous forests. Now they’re cutting down trees to create pastures for cattle.

Small farmers, big problems: Small-scale farmers (often growing cocoa for chocolate) were responsible for most of the forest loss in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Peru. By contrast, large farms — like those growing soy for China — were the main culprit in Bolivia.

From the distance, these data points might seem abstract, but the numbers represent “heartbreaking losses in real places,” Seymour said. “For every area of forest loss there’s likely a species one inch closer to extinction. And for every area of forest loss there’s likely a family that has lost access to an important part of their daily income from hunting, gathering, and fishing. Such loses pose an existential threat to the cultures of indigenous peoples. And for every area of forest loss there’s likely a community downstream that has less access to clean water and is more exposed to floods and landslides.”

Still, she said she’s optimistic that the world can stop leveling forests. Some countries have radically slowed tree loss by passing and enforcing laws. And the United Nations program that pays developing countries to stop deforestation has worked in the few places where it has been funded, she said.

“We know what to do, we just need to do it,” Seymour said.