Corinna Riginos is a Fulbright scholar in South Africa studying overgrazing in the Succulent Karoo.

Monday, 8 Jan 2001

STELLENBOSCH, South Africa

Timm, the leader of the project I am working on, buzzes up to my apartment at 6:30 this morning. I come down with all my stuff for the week, which is not all that much: sleeping bag and ground pad, a few outer layers of clothing, an extra T-shirt (in case the one I’m wearing becomes a bit too odorous), boots, flashlight, binoculars, clipboard, ruler, other various trappings of ecological research, and, above all, sunscreen and a hat.

Timm and the bakkie.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

Downstairs, the truck (or bakkie, as they call pickups here, an Afrikaans word for “container”) is loaded with all sorts of equipment and food for the week. Timm is wearing his usual field attire: a bright green suit, the sort that a gardener might wear, with “Kirstenbosch” emblazoned on the lapel of his jacket. Kirstenbosch is the name of the botanical garden where the National Botanical Institute (Timm’s employer) is based. Timm already has about two days’ worth of stubble, as if in anticipation of the week in the field.

The mountains around Stellenbosch are dazzlingly lit by the early morning sun. Stellenbosch, South Africa’s second oldest town after Cape Town, is situated in a fertile valley famous for its wines. Surrounded by four striking sandstone mountains and studded with tidy vineyards, Stellenbosch is a gem. But its charms slowly fade into the distance as we begin the long drive north.

Our destination, a small village called Paulshoek, is a far cry from Stellenbosch’s affluent, Cape-colonial feel. Paulshoek is part of the “Communal Area,” a chunk of land owned in trust by the government for all the occupants. In the “old” South Africa, during the apartheid days, Paulshoek was part of a “Rural Coloured Reserve.” The people who live there are what the apartheid state would have classified as “coloured,” but if you asked anyone in Paulshoek, he would say “we’re Nama.” The Nama are part of the larger Khoi group of people, traditionally nomadic herders throughout southern Africa’s arid region. But ever since colonists began to claim large chunks of what is now South Africa for themselves, the Nama people became limited to “reserves,” a limitation that was strongly enforced by the apartheid government.

These communal areas make up 25 percent of the Namaqualand region — not nearly enough land relative to the number of occupants, but nevertheless a sizeable chunk of the region. Namaqualand sits in the northwestern corner of the country, a good 600 kilometers up the road that carries traffic from Cape Town to Namibia. It is a long drive; it will take us most of the day just to get to Paulshoek.

Once we leave behind the Stellenbosch winelands, we move on to endless wheat fields. The fields undulate in almost alien fashion thanks to the hundreds of heuweltjies that are packed into the fields. Heuweltjies are mounds or hillocks created by termites over hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years, as they enrich the soil surrounding their termitaria. They appear so regular and neatly round across the landscape, it is hard to believe that something as small as a termite could have done so much.

We wind through our first mountain pass, full of large truck traffic, and descend into the Olifants River valley, a long and narrow citrus-producing region. Outside the bakkie, the world is starting to wake up, farm laborers are starting to go to the field, and the many citrus stalls are just opening up. We continue past the towns of Citrusdal and Klawer, then suddenly burst into the Karoo, the semi-arid biome of which Namaqualand is a part. Big, wide-open space, and a very straight line of highway ahead.

We stop for breakfast in a town called Van Rynsdorp (Van Ryn’s town). Every gas station cafe offers the same fare — greasy and meaty. Timm gets some heart-stopper called an “egg and cheese burger,” as well as a few candy bars. I settle for a toasted ham and cheese, about the most palatable item on the menu.

We drive on.

By noon or so, we reach the “last outpost” town of Garies, which touts itself as “the heart of Namaqualand.” One worries that Namaqualand may not last long with such a small and sleepy heart. In Garies we find lunch in a boerworsroll, the South African version of a hotdog. After lunch, we lose the main highway and turn onto a dirt road. Here we drive through some splendid mountains and farmlands, climbing slightly in elevation. The uplands are home to vestiges of the Renosterveld and Fynbos vegetation that abound back south around Stellenbosch and the Cape, while the valleys are Succulent Karoo. Both Fynbos and Succulent Karoo are among the world’s most diverse ecosystems; South Africa is both blessed and burdened to have two of the world’s biodiversity “hot spots” within the country.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

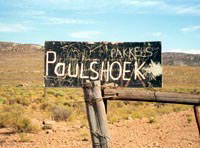

After about an hour on this road, which has taken us northeast to just below the highest point of Namaqualand’s Kamiesberg mountain range, we turn off at a hand-painted sign for “PaulsHOEK” — “Paul’s Corner.”

Soon the town spreads before us, and children and women in huge 18th century-style Dutch bonnets run out of the houses waving as we pass. We stop to touch base with Mervin, the man who runs things Paulshoek-side for Timm. But before long, we take the turn onto the Parkie Straat, which carries us several hundred meters out of town and over a little ridge to the campsite. The site is small and tidy, blanketed with yellow wildflowers, all edifices constructed from reeds and wood, except for a camper that Timm uses as his field office and storage room. We park in front of the camper, thankful to stretch our legs after the seven-hour drive.

My first action is to lay claim to one of the round reed mat huts — matjies in Afrikaans. These huts are shady and cool, and at night you can glimpse the stars overhead through the gaps between the reeds. The floors are level and hard, hand-packed with a mixture of dirt, sheep dung, and water. I sit in the welcome cool of the hut, transfixed for a moment by the calm of the place, the sound of the wind whistling as it passes through the reeds of the roof. It is good to be back in Paulshoek.

Reluctantly, I get up and return to the bakkie. There is more unpacking to be done. We set up tables, lanterns, crockery, water drums, and a gas stove in the kookskerm — a traditional cooking shelter, nestled in a rocky hollow to cut the wind. The walls of the kookserm are made of packed shrub skeletons from a particular shrub species. The walls come only to chest height, leaving the top open for ventilation and stargazing.

There is not enough time to merit a trip to the sites of the various experiments we are conducting, so Timm uses these few hours of waning light to collect his monthly phenology data: He monitors each of approximately 200 plant species monthly for buds, flowers, and fruits. Slowly, this data is building a picture of what time of year each species flowers and sets seed, and whether this process is governed more by time of year or by the weather. This data will allow Timm to make recommendations such as what time of year a pasture should be rested from grazing to ensure that the majority of shrub species reproduce.

The campsite is very rich in species, making it a perfect spot for me to wander or simply sit and observe the iridescent green sunbirds flit from shrub to shrub and the occasional hare bound across the

rocks. The vegetation is all scrubby bushes, thigh-high, except for a handful of Lyceum bushes that come to eye level. The absence of trees makes for a feeling of wide open space, vistas stretching until the next ridge of pink gneiss rock.

By sundown, Timm reappears and says, “Well, I thought we might braai up some chicken tonight, what do you think?” Pretty soon he’s chopping away at the firewood with a hand ax, and a fire is roaring in the kookskerm. I prepare a salad to supplement the grilled chicken. By now it is cold outside, despite the fierce heat of the day, and we stay in the warmth of the kookskerm. We eat and talk, planning the week’s work, catching up on the past month’s events, enjoying the tranquility of the night. Tomorrow the real work begins.

Tuesday, 9 Jan 2001

PAULSHOEK, South AfricaÂ

At 5:45 a.m., the first rays of sunlight come through the walls of my hut, and I roll over to glance at my watch. Time to get up. Heavy sleeping-bag-sleep is still upon me as I pull on my pants and boots, then head down to the “Enviro-loo,” a composting toilet with such a splendid view of the rolling Paulshoek hills that it has been dubbed “the throne of Namaqualand” by those who work on the Paulshoek project. On the return from the loo, I splash some water on my face and brush my teeth. Then I pack my backpack for the day.

Breakfast consists of tea and rusks. I opt for black tea, as opposed to the favored South African rooibos (red bush) tea, and several rusks — hard, bread-like biscuits that every good Afrikaans ouma (grandmother) makes — dunked in the tea make a filling start. Timm eschews the tea, instead preparing himself a cup of Horlick’s, a malt-flavored vitamin and calcium drink, a popular beverage around here.

By 7 o’clock, we are in the bakkie and on our way out of the campsite. We drive back out to the main road, then continue for several kilometers down this road before turning southeast toward the area called Slootjiesdam. This is where I am doing most of my work, although other projects are underway in other parts of the greater Paulshoek area.

Sors Cloete, a Namaqualand herder.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

The Paulshoek project is part of a larger study, funded by the European Union, which is aimed at understanding the ways in which socio-economic and bio-physical factors interact in southern African communally owned rangelands, with particular emphasis on the promotion of sustainable development. There are three teams working on this study: one in Botswana, one in Lesotho, and one in South Africa. Each country team has focused on a particular area as a case-study, and in South Africa the focus is on Paulshoek. The Paulshoek team consists of senior researchers from both the natural and social sciences, as well as numerous students. Some of the key research questions include: What sources of income drive the village economy? How do the villagers interact with the land? What do they take from it, and what are the impacts of their use of the land? What actions can be taken to promote sustainable development? The study attempts to look at Paulshoek as a system, rather than focusing on one specific attribute of the area.

As a person of a more natural-sciences orientation, my work in the Paulshoek project forms part of a larger investigation of the impact of livestock grazing on the vegetation of the range. The grazing practices of the communal areas, which comprise 25 percent of Namaqualand’s area, are considered to be the main threat to the incredible diversity of plants in this region. These areas are very heavily grazed by sheep, goats, and donkeys — grazed at more than twice the recommended intensity. Herding, and keeping herds, is a way of life for the villagers; animals are akin to a bank investment — you keep as many as you can and save them for later use. Because the land is communally owned, everyone has the right to graze as many animals as he or she wants, with the result that the number of animals in the area is much higher than what scientists’ best estimates suggest is sustainable. Some people would suggest that the land ought to be divided up and privatized to avoid this “tragedy of the commons,” but the large number of people living in the communal areas means that each person would receive a uselessly small parcel of land.

Livestock husbandry is conducted in a traditional manner. Herders follow their herds during the day, then return them to a paddock, or kraal, at night. Herders typically live in a small hut and kookskerm adjacent to the kraal. This practice of returning the herd to a stockpost at night is thought to be highly destructive to the surrounding vegetation; it creates a center of intense degradation around the kraal. For this reason, I am conducting a study of the changes in plant diversity and population dynamics (e.g., reproduction and survival) as one moves progressively farther away from a kraal.

The kraal I am focusing on belongs to a herder named Sors Cloete. As we approach the kraal on the narrow dirt track, Sors’s dog Tyger runs out barking his seal-like bark, with a Chihuahua-sized companion and a puppy in the rear. The dogs exuberantly compete for our attention as we climb out of the bakkie.

“Goeiemore, Sors! Hoe gaan dit?”

Sors’s house.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

We enter Sors’s kookskerm and take a seat, each of us on an upturned bucket, as Sors prods his breakfast fire and rolls a cigarette out of tobacco and newspaper. Like almost everyone who lives in the Communal Area, Sors is small and slender with strikingly high cheekbones, evidence of his Khoi ancestry. He is a dedicated and knowledgeable herder, making his living by herding someone else’s animals for the pitiful sum of 250 rand a month (about $30). His wife and four children live in Paulshoek village, only about 10 kilometers away, but with no transportation they can only visit every second weekend. Except for these visits, Sors lives by himself in a small one-room shack made of aluminum sheeting with the odd flattened tin can hammered on to patch holes in the sheeting.

After catching up on the month’s gossip with Sors, Timm and I head out to start the day’s work. Two months ago, I planted 40 seedlings at each of eight distances away from the kraal, to see if they were less likely to be trampled or eaten when farther away. Now, I must survey the seedlings for survival and growth.

Timm drops me off two kilometers from the kraal and drives off to change the memory module on the weather station he has set up in another region of the Paulshoek area. I start my task of surveying at the two-kilometer distance, then make my way sequentially closer and closer. By 9 a.m., I have shed my layers down to the T-shirt. By 11, it has become very warm, and a long two hours until lunchtime loom before me.

In the distance, I can see the bright green silhouette of Timm, indicating that he has returned from his trip to the weather station and is now collecting seeds for next year’s projects, whatever they may be.

At around 1, Timm fires up the bakkie and comes in search of me. He has to try several different roads before he finds the one that will meet up with where I am at the 800-meter mark. He arrives, and we pull out the large cooler from the back. Slice some hearty multi-seed bread and cheese, and Timm spreads an avo onto his sandwich. The bakkie provides only the slightest sliver of shade. We seek it hungrily, bu

t it is not even enough to shade our heads. “We must get some brollies,” says Timm.

Reluctantly, I get up from lunch’s respite to continue my work. Timm goes off to collect data on some plant populations he is keeping tabs on. By now, my knee is sore from kneeling, the heat is brain-scrambling, and my drinking water is too warm to provide relief. Push on.

The grass is greener on the other side.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

Around 4:30, Timm comes back to fetch me. Time to go see Hansie, the commercial farmer (like all commercial farmers in South Africa, at least until land reform takes place, he and his wife are white Afrikaners), on the other side of the fence from the communal area. And what a contrast it is, crossing that fence! Different, more diverse species, all abloom. It takes almost half an hour to reach the home of Hansie and Petra Visser; when you can graze only one sheep for every six hectares of land, properties must be sizable to maintain a herd without destroying the landscape.

Timm catches up with Hansie and Petra, gossip, pleasantries. Although they both understand English, they are shy to speak it. Timm grew up speaking English at home, but his command of Afrikaans is quite good, as it must be for him to work in the communal area, where almost nobody speaks English. So they converse in Afrikaans, while I sip the cup of rooibos tea Petra has brought and struggle to understand a few scraps of the conversation. Eventually, Timm brings out a set of spiral-bound books and sits down with Hansie to talk about the livestock. Hansie tells what he has sold and bought, what has been born, and what has died. He sells his sheep for meat. The sheep of the Karoo are known for their tasty meat, a result of their diet of aromatic shrubs. This data that Timm collects will be used as a comparison with comparable data from the communal area. The intent is to see what economic benefits come of grazing fewer animals less intensely, using the land in a more sustainable manner.

Finally, around 6:30, Timm and Hansie finish discussing the stock data, and we climb into the bakkie to head back to the campsite. The sun is dipping behind the mountain, and the temperature has become very pleasant, soon to be cool. Thoughts turn to dinner.

Back at the campsite, I rummage through the food bins to see what we have on hand. Time to improvise. I throw together a few vegetables and tomato sauce and make a pasta dinner. Washed down with another cup of rooibos tea. We talk of careers, family, South African and American culture, life. We stare up at the cloudless sky and identify the few constellations we know between the two of us — Orion, the Pleiades, and, of course, the Southern Cross. By 10, we are weary. I make my way to my hut and Timm to the camper.

Wednesday, 10 Jan 2001

PAULSHOEK, South Africa

My alarm blares in my ear: 5 a.m. Up. No wasting time this morning. But it is so beautiful outside, all the brilliant predawn colors smeared across the hills! I could sit and gawk for ages … but no, we must be at the kraal before sunrise. Timm is already up and boiling the water for tea. I hurriedly pour some cereal into a tupper for later consumption and try not to delay our departure by my early-morning sluggishness.

This is the morning — once per month — when Timm weighs all the kids and lambs in Sors’s herd. He wants to see how rapidly they put on weight, especially relative to the animals in Hansie’s herd, which benefits from a much less degraded range. In order to weigh the animals, we must be at the kraal before Sors lets them out for the day just past sunrise.

Big goat, little goats.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

By the time we reach Sors’s kraal, it is quite light out. I shiver and impatiently will the sun to poke up above the hills to warm my numb hands. We head over to the pens where the goats and sheep spend the night. With a few (seemingly) easy motions of his stick, Sors separates out the small goat kids from the rest of the herd and guides them into a small enclosure. Now the hard part: herding the rest of the animals into a separate pen, small enough to keep them all tightly packed so that individual animals can be singled out. Although the goats are docile, the sheep do not want to be herded. They balk and break ranks and blow gobs of snot all over the place. Finally, after several attempts, we manage to pen them all in.

Timm brings out a small scale, with a sling that each animal must be put into, and we begin the process of weighing all the lambs. Each one is identified by a combination of photograph and Sors’s nicknames. “Swartkop, ‘n ram,” Timm calls out, and Sors goes in search of the little black-headed lamb. The sheep are difficult, kicking and putting up a fight, but at last we can turn to the little goat kids, which are much smaller and gentler. One little animal, only three days old, butts its head at the back of my leg insistently, hoping I turn out to be its mother.

We finish the weighing by around 7:30, and Sors opens the gates to send the animals out to graze. They quickly make off to the hills, except for the goat kids, which will stay behind to spend the day in the area in and around the kraal. Before three months of age, the goat kids are unable to keep up with the fast-moving herd.

Timm must talk to Sors for a while, then go back to Paulshoek to meet with Mervin. Mervin collects monthly stock data from each of the 26 herders in the area — how many animals were born, died, bought, sold, what medical treatments did they receive, and were they given dietary supplements? Timm must transcribe this data into his own set of logbooks, then discuss matters with Mervin. Timm laments that he will soon be losing Mervin to politics, as he has just won a seat on the district council. But it is good for Mervin and very good for the village.

While Timm spends the rest of the morning in meetings in Paulshoek, I continue collecting data for my study of the regions surrounding Sors’s kraal. I’ve got plots set up at each of the eight distances, and in each plot I must remove dung, measure shrub heights and widths, count the number of fruits on each plant, and more. Today I am removing dung, so that I can get an estimate of how many animals are passing through that area. It is tedious work, especially close to the kraal where there is copious dung on the ground.

At last, Timm arrives — lunchtime. The respite from work is much-needed, as is shade, but there is no shade to be found. Miraculously, it is cooler inside the bakkie than outside, so I sit there to eat my bread, cheese, cucumber, and carrots.

After lunch I resume work, and Timm goes back to talk to Sors again. Sors is writing small essays on each of the plant species that is found in the area around his kraal, and Timm must spend some time connecting the right scientific species name to each common name that Sors uses. Sors has a remarkable knowledge of each of these plants, as he should, after many years of observing them day after day. He is also making maps of the routes the animals walk every day, so that we can see which areas are most intensely grazed. Sors draws the routes onto a transparency that overlies an aerial photograph of the area. Another student of Timm’s is digitizing these routes and analyzing them to try to understand what factors affect the grazing habits.

Timm, my favorite man in green, atop the bakkie.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

At around 3:30, the bakkie and its fearless green driver find me just finishing up my day of dung collection. I’ve finished up my water bottle, too, and am thirsty for more. Timm is also out of water, and we decide that we must make a trip back to the campsite to hydrate ourselves. There is a borehole near to the kraal from which Sors and the herd drink, but Timm says this water is brackish and may cause our city-adapted stomachs grief if we drink it. So we drive to Paulshoek, half an hour to get there and another half an hour to return on these sandy and sometimes eroded dirt roads. We use this time to discuss the progress on my study — what patterns seem to have emerged, just from casual observation.

“How do you feel about things?” Timm asks.

“Good. My seedlings are dying from drought, though.”

“Are you depressed about that?” he prods.

Timm is very concerned that his students feel good about where they are with their work. Sometimes I wonder if he shouldn’t have become a therapist. He is incredibly easy to talk to.

By the time we return from our water-fetching mission, the temperature outside is much more pleasant. It gives me a second wind for these last several hours of work. We work together, continuing the task Timm began yesterday, tagging and measuring individual shrubs of several populations, individuals Timm will revisit in subsequent years to see how this species is surviving.

The green(ish) hills of Africa.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

At around 7, we call it quits. Brief stop at Sors’s to bid him tot siens and we are on our way back to the campsite. We drive in silence, tired, awestruck by the late afternoon illumination of the koppies, the rocky hills that are characteristic of this region. There is a quiet calm to the landscape at this hour.

At the parkie, I wash my sheep-shit-dirty hands, take off my boots to the relief of my feet, sit still in the peace of the place for a moment. Timm boils water for a cup of instant soup, and he starts in on the wood chopping. Dark descends slowly, and we debate what to eat for dinner, finally settling on braai-ed vegetarian sausages. Timm says they have the consistency of sawdust, but I find them delicious.

Eventually the conversation turns to the inevitable topic in South Africa: racial issues. Timm, who spent some time in jail for protesting apartheid in the 1980s, is one of the few people I’ve encountered who genuinely wants to promote change in this country and is acting on his desires. There is so much work to be done, though. The first democratic elections were already seven years ago, but the poor are still desperately poor, trapped by economics as much as they were by apartheid’s ugly policies. The soaring optimism of 1994 has faded now, and people are becoming bitter and resentful. Anger is starting to come out from more than just an extremist minority.

“It is amazing, though, that the transition from the old South Africa to the new happened so peacefully,” I say. “I mean, the potential for a disaster was definitely there.”

“Mandela,” says Timm. “What an incredible man, so gentle and persuasive. I think it is thanks to him that the bomb was diffused. Of course the anger is starting to surface now. It’s understandable. Look at you guys in the U.S. — how many years since the civil-rights movement? And there is still so much anger.”

I nod sadly.

We stare into the red coals of the fire, solemn and pensive. As the fire is waning, so am I. It has been a long day.

Thursday, 11 Jan 2001

PAULSHOEK, South Africa

Today, I sleep until the luxurious hour of 6:30, when I’m awakened by the sound of Timm unloading the food crates from the camper. He says he wakes up earlier and earlier all week in Paulshoek, so by today, Thursday, he will have been up since 4.

It is hot outside already, foreshadowing that today will be a scorcher.

Enviro-loo, teeth, tea, rusks, ready to go.

This region is part of the Succulent Karoo, so-called for the amazing diversity of succulent plant species.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

Today I start in on the plant measurements in my plots. I am recording general attributes, such as which species are present and how many of them there are, the amount of plant cover versus bare ground, the size of the average shrub, etc. In addition, I am focusing on two important species, looking at how their density, size distribution, and fruit production changes between the more heavily and less heavily grazed areas.

Close to the kraal, where I begin, there are not so many plants to measure — a handful of palatable shrubs that look like pruned hedges after years and years of goat nibbles. The rest of the plants are all healthy-looking Galenia africana, the toxic shrub that flourishes in heavily grazed areas, so much so that it is commonly known as kraalbos. As I progress away from the kraal, however, the vegetation becomes denser and more diverse, with less and less Galenia. The shrubs are never so dense as to make walking at all difficult, though.

Timm has gone off to find all the kraals that have relocated in the past several months and take GPS readings of their new locations. Herders may move as often as every few months, or as infrequently as every 10 years. Sors has staked out a prime location and is unlikely to move any time soon, but others have only fields and fields of unpalatable Galenia at their disposal.

Timm also has a Paulshoek Development Forum meeting to attend. A small but refreshingly young and dedicated group of villagers is eager to promote development in Paulshoek, and Timm does what he can to lend a hand, providing advice and ideas, and helping them to secure small project grants.

I work through the morning alone, save for a brief visit from Bassie, the herder of the next kraal over. He often brings his herd through this same area that Sors’s herd grazes. Bassie always seems a bit bemused and befuddled by what these strange scientists are doing. I struggle to communicate with what few phrases of Afrikaans I know, but am restricted to a rather mundane dialogue:

“Hoe gaan dit?” (How are things?)

“Goed, lekker! Hoe gaan did met jou?” (Good, nice. How are you?)

“‘n Bietjie moeg, mar goed. Vandag is warm, nie?” (A bit tired, but good. Today is hot, no?)

“Baaie warm!” (Very hot!)

Bassie moves on, and I resume work.

The Paulshoek skyline.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

Timm returns around 1 with the lunch. We eat. Timm relates the latest news from Paulshoek: The chair of the development forum has stolen a diesel pump from the village and sold it to another village. He pleads innocent and no one can prove that he is guilty, but everyone knows he did it. Disappointing news.

After lunch, Timm helps me continue with my work. It is amazing how much faster things proceed with two people. We make good progress, winding down for the day by 5. I am relieved to have finished everything I needed to do during this trip to Paulshoek, and Timm is happy that we can leave tomorrow morning and be back in Cape Town by mid-afternoon.

We bid good-bye to Sors until next month and then make our way

back from Slootjiesdam. The wind whipping in the window of the bakkie is refreshing, and I savor the colors of the hills, the pink gneiss rock outcrops splashed with the purple flowers of Leipoldtia shrubs. Everything will be much drier, browner, next month.

It is our last night at the campsite, time to try to finish up the fresh vegetables that we’ve brought all this way. I throw together a vegetable curry with rice. Timm takes a shower from a hoisted shower bag while the food cooks, but I opt to stay dirty. It’s too cold outside already to contemplate a shower. I am sure I smell, and half of the color that this week has added to my arms is from the red Paulshoek dirt, but there will be plenty of time to wash thoroughly tomorrow.

As we finish eating our dinner, two silhouettes appear walking up the path toward us. Timm immediately recognizes the figures of Vytjie (pronounced “Fekkie”) and Bheki and calls out to them in greeting. “Goeienaand!,” they reply.

The two visitors pull up stools around the fire in the kookskerm, and Timm puts on a kettle for tea. Vytjie, age 18, is strikingly gorgeous with her high cheekbones and glimmering eyes. Bhekie, already tired-looking at 32, sits in quiet reserve as her younger companion spins the gossip mill with relish. Vytjie tells all sorts of tales, most of which I understand only scraps, but Timm translates the gist for me. Last weekend, Vytjie says, she went for a joyride to Springbok with some guys she had just met in Garies, and it turned out the car was stolen and the guys all had guns. Timm scolds her for being so naive as to get in the car with these unknown fellows. Vytjie seems nonchalant. She goes on to tell more news, of the way AIDS is affecting the village, of drunken brawls, of a man who raped his four-year-old daughter last week. Even the easy-going village of Paulshoek has its share of problems.

When the women have finished their tea, Bheki at last speaks up, asking for a ride to Garies when we leave tomorrow morning. Garies is the nearest town with a bank, stores, doctor, hospital, everything, but it is a struggle for Paulshoek residents to come and go. Only a handful of villagers owns vehicles, and most will charge 140 rand (about $18) for a trip to Garies and back. When the household income hangs around 250 rand (about $31) a month, trips to Garies are hard to afford.

Timm agrees to give Bheki a lift, and our guests thank us for the tea and make their way back to the village. We wash what dishes there are, then enjoy the silence of the evening under the full moon. The silence is complete and comforting, unlike the smothering silence of the urban context. I savor this peace.

Reluctantly, I make my way to my hut for the last night of Paulshoek lekker slap (good sleep). Timm says we can take our time in the morning — no need to rush out at the crack of dawn. But knowing him, he will be packing up the campsite by 7.

Friday, 12 Jan 2001

PAULSHOEK, South Africa

I am awake by 6. It’s my schedule, these days. But I do take time to enjoy my breakfast, then pack up the contents of my matjies hut. I will miss the hut until next month.

We pack everything away into the bakkie and camper, bit by bit. There are many little components of this and that to keep track of: mattresses, sleeping bags, lanterns, crockery, tools, data books, GPS. But we get it all sorted out, and by 8:30 we are ready to roll. Roll through the village one last time with Timm holding his arm out the window and waving continuously. “I feel like a beauty queen when I’m here,” he chuckles.

The view out the bakkie window.

Photo: Corinna Riginos.

And then we are gone, on the road again for the long return drive. More road, more greasy roadside cafes, more hitchhikers begging for a lift to the next major town.

The long road stretches in front of us in a straight, unending line. We chat.

“If you could travel to anywhere in the world, where would you go?” I ask.

“Nowhere,” replies Timm. “I am really content with where I am. And I’m still growing here in so many ways. Take this Paulshoek project. I’ve been coming to Paulshoek for three years now, and every time I come up I learn something new. It’s a lovely existence. But there is so much more to be done.”

I admire these words, this spirit, this desire to do what you can do in your own little corner of the world. Still, I am young, grappling with the bigger issues, not content to settle in any one place. I want to know what sustainable development truly means and if it is possible. I want to know if there is any way to conserve the planet’s diversity other than the tragically useless appeal to conscience. I want to know what I can do that will have meaning.

Being out at Paulshoek gives you so much time and space to think. Somehow, when I am there, everything seems unanswered and yet crystal clear. It has something to do with simplicity.

At last, after a seemingly interminable drive, we pull into the outskirts of Stellenbosch. It is Friday afternoon, and the students are getting ready to celebrate week’s end. Everything seems surreal — too many cars and people, obstructed skylines, too many walls of brick and concrete.

I’m back.