As far as the North Fork of the Gunnison River in western Colorado is concerned, there’s good news and there’s bad news.

On one hand, it drains one of the most beautiful valleys on the planet — its headwaters tumble from the Ragged and West Elk mountains into the broad, gentle North Fork Valley.

The Gunnison River — ain’t it pretty?

Photo: Lisa Jones.

On the other hand, the river has been used hard for decades. Coal mines, ranches, and orchards dot the valley, each of them diverting water, often with cheap and ecologically destructive methods. There are three gravel operations in the 12-mile stretch of river between the little towns of Paonia and Hotchkiss. (Colorado is one of the handful of states that still allow in-stream gravel mining.) From 1948 until about 1980, the county controlled flooding and secured land for agriculture and housing by bulldozing a deep channel straight down the river. The result is a badly degraded waterway whose natural meanders have been erased and whose banks have been severely eroded.

Good thing there’s a supernaturally energetic and cheerful engineer named Jeff Crane working to rehabilitate the North Fork. On a recent afternoon, he bounces across Hotchkiss’s Main Street in rubber boots and Carhartt jeans, fairly leaps into his Pathfinder, and drives to the riverbank.

“This river has so much potential!” he shouts happily. He loves his job, and it’s easy to see why. The sun is high. The reconfigured banks are fringed with red willows that Jeff transplanted himself. The water, low and clear, is making its way through mounds of gravel being rearranged by a septet of heavy vehicles, under Jeff’s careful guidance. And under an exuberant blue sky, the West Elk Mountains are dusted with new snow.

How It All Began

Jeff first got involved with this project in 1996, when a rancher named Calvin Campbell convened a group of locals concerned about the state of the North Fork. Everyone — ranchers, environmentalists, kayakers, orchardists, gravel miners, irrigators, riverfront landowners, and average concerned citizens — agreed they wanted to reduce erosion. They formed the North Fork River Improvement Association and hired Jeff, a civil engineer, to conduct a morphological study of the riverbed.

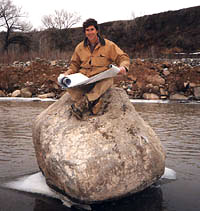

Jeff Crane — you’d grin too if you had his job.

Photo: Lisa Jones.

He completed the study, but didn’t stop there. The longtime outdoorsman was hooked. He started raising money to do more, garnering some $340,000 in cash and in-kind contributions from 24 sources, ranging from government agencies to environmental groups to coal mines. He talked to the gravel-pit operators and got two of the three to move their operations out of the streambed and into the floodplain.

He has involved as many local people as possible. Students at Mesa State College in nearby Grand Junction can take a one-credit course in bioengineering, which involves working with Jeff for four days and taking a day-long workshop from an expert Jeff brings in. Local high school kids have made documentaries and web pages on the project.

A Healthy Diversion

Today Jeff is overseeing the construction of a new irrigation structure, which will efficiently divert the amount of water allocated to local farmers and ranchers. Up until now, water was diverted by driving bulldozers into the middle of the river and plowing out a big dike. This method was quite inefficient, though, and it diverted about twice as much water as the locals were entitled to. The excess water not owned by farmers and ranchers would eventually flow back into the river, but the fact it was taken out at all stressed the ecosystem.

“It’s not that the people don’t care,” says Jeff. “It’s that they didn’t have any money.” He solved that problem by securing a $100,000 grant for constructing the new diversion structure.

Keeping the kayakers happy.

Photo: Lisa Jones.

Jeff is also reconfiguring sections of the river to have meanders, wetlands, backwaters, and floodplains, all made stable with willows and cottonwoods. He makes undercuts and arranges rocks to create trout habitat. He is saving one big rock to make a wave for local kayakers.

“I’m looking to strike a balance — fish habitat, boating habitat, wildlife habitat,” he says. “And to divert water to sustain agriculture in this valley, so we don’t have a bunch of condominiums lining this river.”

He knows what he’s talking about. Before moving to the area in 1994, Jeff was a project engineer who platted lots and developed roads for a luxury development on a golf course outside Denver. “I got disgusted,” he says. He went to Africa for a few months, spent some time in Alaska working in a salmon cannery, moved to Vermont, and finally landed in the North Fork Valley, determined to make a life here even if he had to pick apples. But it didn’t come to that. Jeff found some development work and attended numerous river-restoration courses.

It all paid off. Now he’s got the perfect job — designer of a new river. He gets to spend his days outdoors, planting willows and cottonwoods, moving rocks, talking to people. “I’m trying to prevent the same thing I spent 15 years building,” he says. “I’m as happy as could be.”