At midnight one late-September evening, a convoy of 18-wheeler flatbed trucks carting 14 houses (some whole, some in parts) and thousands of square feet of solar panels rolled past the Washington Monument, drove along the National Mall, and headed up to the front lawn of the Capitol building. Upon arriving, the first truck in line barreled through a yellow ribbon held by members of a hooting and hollering welcoming committee, as if it had finally reached the finish line. But the race was about to begin.

Airstream of

conscientiousness.

Photo: Warren Gretz, NREL.

Fourteen teams of architecture and engineering students from universities nationwide had arrived in Washington, D.C., for the Solar Decathlon, a Department of Energy-sponsored competition to build the ultimate solar-powered home of the future — sophisticated in design, super-efficient, and capable of generating enough solar electricity to meet the demands of a mainstream, energy-lavish lifestyle. On Sept. 26, after a week of nonstop construction, more than 100 bedraggled students and professors running on the fumes of their save-the-world adrenaline unveiled their entries in a ceremony hosted by Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham.

Shakespeare himself couldn’t have crafted a more appropriately tempestuous setting for the opening pageant: Backlit by bolts of lightening and nearly drowned out by pounding rain, Abraham chirped, “Renewable energy is here to stay. It’s real, it works, its future is bright!” The thunder offered a fitting retort to the cheery prattle, as if to scold the emcee for treating renewable energy in practice as more as a sideshow curiosity than a meaningful technology. Still, the ceremony wasn’t all lip service: One after another, executives from the private-sector companies sponsoring the event — Home Depot, BP Solar, and the American Institute of Architects, among others — stood up and rattled off stats and pledges that grounded Abraham’s flimflam in reality.

Spencer Abraham at the

opening ceremony.

Photo: Warren Gretz, NREL.

“Solar technology is not 40 or 50 years out; it’s what we call state-of-the-shelf,” said Jonathan Rosen, director of business development for Home Depot, which gifted a $6,000 shopping spree to each team of decathletes and has recently expanded its distribution of solar products from three to 61 stores nationwide. Then came Harry Shimp, the CEO of BP Solar, which provided solar panels for the teams at a discount: “This is more than just an interesting technology. Demand for [these kinds of home solar systems] is growing at 35 percent a year.” And in a little jab to the DOE, he added: “We hope the government will consider a national net-metering plan, tax incentives, and incorporating solar into all new [federal] construction.”

Next up was Norman Koonce, executive vice president and CEO of the American Institute of Architects, that pillar of tradition representing 70,000 architects nationwide: “We are celebrating one of architecture’s most important advancements … on one of the most prestigious pieces of real estate in the world!” he beamed. Koonce went on to note that more than a third of all AIA members now boast energy-consulting services and sustainable design experts — a “considerable increase in recent years and a sign, indeed, of a growing movement,” he said later in a phone interview.

Some Assembly Required

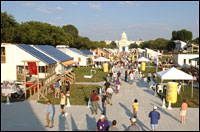

As the ceremony came to an end, the sky began to clear and the audience was alight with megawatt smiles. A brass quartet tooted the national anthem, and even the young, hipper-than-thou architects and engineers held their hands over their hearts and sang along. With that, the students paraded out of the tent onto Decathlete Way — the main drag of the makeshift “Solar Village,” lined on either side with one-story structures sparkling like huts in the Emerald City.

Crowded houses.

Photo: Warren Gretz, NREL.

For all the sci-fi fantasy inherent in this event — which Richard King, its director, called a “race to the future” — there was a surprising amount of down-home Americana on display. Apart from Virginia Tech’s far-out living pod with transparent walls, most of the homes looked pretty familiar, even with the glittering roofs: here a traditional colonial, there a Southern-style shotgun house with a solar-powered Airstream trailer. The teams, each of them consisting of 50 to 100 students and professors, hailed from all over the nation — as close as Maryland and as far as Texas, Alabama, Missouri, Colorado, and even Puerto Rico. The decathletes spent two years building their homes and then hauled them thousands of miles onto the lap of the federal government. In at least as impressive a feat, they managed to raise up to $500,000 apiece in donated equipment and funds for their projects. (The shipping costs alone, in the case of Puerto Rico, totaled nearly $100,000 — and half that for most of the others.) This was, in other words, more than a glorified science fair.

Six members of each team were expected to “operate” (aka live in) the homes from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. throughout the week-long duration of the contest, which ended earlier this month. Architectural design, livability, and various forms of electricity use were evaluated in 10 separate contests. Electronic sensors and monitoring equipment took constant readings of 30 “data points” in each home, measuring everything from air temperature and moisture levels to hot water and refrigerator/freezer temperatures to the amount of light falling in every nook and cranny of the interior. Even the number of towels and dishes that had to be washed every day were monitored, along with the number of meals cooked and the types of errands run in the electric cars supplied by the DOE for all team transport. (The car, like everything else, had to be charged by the rooftop solar panels.) To top it off with a digital-era flourish, each home had to run a TV for six hours per day (the national average); a computer with a satellite Internet connection had to remain on 24 hours a day.

Building Momentum

One of the judging categories notably absent at the decathlon, however, was affordability. While the contest entries did an admirable job taking into account the mainstream lifestyle, they were not as attuned to the mainstream budget. The houses in the competition were about the size of a spacious living room, and yet they cost between $150,000 to $500,000 to assemble — hardly a practical price tag for your average consumer, especially given the heavily discounted parts and the free design and construction for the decathlon entries. Granted, each home was one-of-a-kind and therefore more expensive than a mass-marketed version would be, but in most cases the technology on the roof cost about as much as the rest of the house. “I can’t see solar homes as a mainstream revolution — not just yet anyway,” said Treylon Raines, 22, leader of the team from Tuskegee University in Alabama. “It’s just not economical enough. I’ve got about a $70,000 system on this roof and it would take me something like 60 years to pay it back [with savings from electricity bills], which is twice the guaranteed lifespan of the technology.”

Sun beam appliances, inside the

University of Puerto Rico house.

Photo: Warren Gretz, NREL.

If King is correct that the decathlon is “a race to the future,” then it will have to be a future in which solar is cost-competitive with traditional electricity. Many people close to the renewable energy industry are convinced that will happen — that prices for photovoltaic (PV) panels will continue to plummet, as they have consistently for the past decade. The key to economic viability and to making “solar” a household term, they agree, is acceptance of the technology by mainstream distributors, architects, and engineers like those sponsoring and participating in the decathlon.

From an engineering standpoint, market acceptance hinges on solar matching or outperforming other energy technologies; from an architectural standpoint, it hinges on solar appealing to the aesthetics of consumers. The latter, in many ways, is the biggest challenge, which explains why the design contest in the decathlon was worth twice as many points as all the others. It was judged by a panel of six experts led by executives of AIA and celebrated Australian architect Glenn Murcutt, winner of this year’s Pritzker Prize (the architecture-world equivalent of the Pulitzer).

Little house on the big mall:

the University of Virginia

house.

Photo: Warren Gretz, NREL.

The University of Virginia won the design contest by a unanimous vote. In a later phone interview, Murcutt commented that, “Virginia had a design that showed that a solar home is not just about plunking a panel on top. It must be as poetic as it is rational. It must consider every aspect of sustainability, from the building materials to the insulation and ductwork to the way light is used. It must be whole-building sustainable design, and all those components must integrated in an elegant way.” Green architects believe that all solar structures must be approached holistically: Before a designer even considers putting solar panels on the roof, she has to create the most efficient structure possible. What, after all, would be the point of buying expensive PV panels to power an air conditioner or heat a house if the fruit of all those hard-won electrons leaks out of poorly insulated walls and windows? And why put loads of light fixtures in the house (and expend energy to power them) if you can design the home to have abundant natural lighting?

The Virginia team covered all its bases in terms of super-insulated walls and windows and energy-efficient appliances, and then they took the idea of sustainability one step further. They used reclaimed copper cladding and wooden trellises made from shipping crates for the exteriors. On the interiors they maximized natural lighting by installing floor-to-ceiling insulated glass on the entire south-facing wall and adding movable walls to create shade in the summer and let in light and warmth in the winter. They used maple paneling and translucent ceramic tiles on the walls to create a constant cozy glow. To add some high-tech splash, they put a mirror dish on the roof that collects daylight and feeds it through fiber-optic tubes to the interior for non-electric lighting. There was even a “smart wall” — a large computer monitor in the front hall that controls all the appliances in the house. The team programmed it to change colors according to the temperature of the house (it blushes pink when the houses is warm and turns blue when the house is cool) to give a sensory understanding of how the house works.

“Really we’re trying to change every convention that anyone has about how you build a house, how you power that house, how your house actually operates when you are there and not there, how you relate to it, how it relates to everything else,” said Adam Toffler, 28, an architecture grad student at UVA and leader of Team Virginia.

The Future Is Now

Toffler’s sense of optimism and revolutionary spirit could be felt among many of the Solar Decathletes, but not all of them believed that the revolution was a matter of changing every convention. “This is not about reinventing the wheel,” said Matthew Henry, 28, leader of the team from University of Colorado at Boulder, which placed first in the overall competition. (Virginia placed second.) “We didn’t want to totally reinvent the look and feel of a traditional home, simply because we want mass appeal. We want people to identify with it and buy into it. Our original design was artistic and sculptural with curved walls and all, but we scrapped it. We decided to go for mainstream America — lowest common denominator. That’s where the revolution lies.”

To Boulder go where nobody

has gone before, the

University of Colorado at

Boulder house.

Photo: Warren Gretz, NREL.

Whether you believe that the revolution will entail a wholesale reimagining of the American home or a subtler shift to sustainable building, it’s clear that architecture and the environment are becoming inextricably linked — and that the revolution, whatever form it takes, will widen as the decathlon student participants and their peers go off into the professional world.

“The future is right here on the mall right now, all these schools and all these students,” said John Quale, professor of architecture at the University of Virginia, “I firmly believe that more significant change will happen in the future of architecture with this generation of students than any other. These students really believe that ethical issues and aesthetic issues can’t be separated from each other.” The way the topics are being taught is different, too. Solar design is merging the disciplines of architecture and engineering. In the past, architects have always hired engineers as consultants, but a whole-building green design requires collaboration and a multidisciplinary approach from the outset.

According to Kim Tanzer, who co-chairs the sustainability task force for the board of directors of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, almost every one of the 120 architecture schools in the U.S and Canada have incorporated principles of sustainable design into their curricula in the last five years. At least a third have included classes dedicated to studying sustainability. But, she emphasized energy-efficient architecture is a whole-building philosophy, and solar is just the cherry on top: “This is a much more comprehensive movement. It’s not just about adding one or two new classes but integrating these concepts throughout the entire curriculum.”

Surveying the hundreds of students hammering together their mini El Dorado of energy independence, Matthew Henry of Team Colorado agreed: “In many schools, sustainable design is still treated as a specialty, which is a shame. They’re looking at it as a perk and not a standard, which means they can’t see the reality of the situation: You can’t have good architecture without principles of sustainability anymore. Buildings that are efficient and respond to their environment are simply smart architecture.”