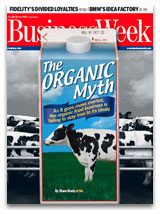

A fine feature story in Business Week this week — The Organic Myth, by Diane Brady. “As it goes mass market, the organic food business is failing to stay true to its ideals,” the cover proclaims.

When I first glanced at the mag, I expected rah-rah boosterism for corporate organics and spite for old-school purists, but the article actually struck me as a pretty fair assessment of the culture clash between the organic ethos and the Big Biz model — the gist being that the two are remarkably ill-suited. Corporate enthusiasm for organics notwithstanding — and there’s plenty of enthusiasm out there, from Wal-Mart to General Mills to Kellogg and beyond — these two approaches to comestible commerce look increasingly irreconcilable.

None of this is new, of course — our own Tom P. has written about the issue (and I’m interested to hear his assessment of this story). But this is the first article that’s made me think the organic juggernaut is really about to blow up into a big ol’ mess. Not just organic getting watered down, as is already happening, but the whole system breaking down, unable to support the new model of globally sourced organic items pouring into processed foods and mega-stores. Demand is outstripping supply by huge margins, corporations are demanding lower prices, production is being offshored to unreliable suppliers, individuals are growing even more confused about what “organic” means.

The article starts and ends with Stonyfield Farm, long a respected producer of organic yogurt, and now a corporate-owned company that’s lost the respect of purists even while failing to live up to the profit demands of its parent firm.

Stonyfield’s organic farm is long gone. Its main facility is a state-of-the-art industrial plant just off the airport strip in Londonderry, N.H., where it handles milk from other farms. And consider this: Sometime soon a portion of the milk used to make that organic yogurt may be taken from a chemical-free cow in New Zealand, powdered, and then shipped to the U.S. True, Stonyfield still cleaves to its organic heritage. For Chairman and CEO Gary Hirshberg, though, shipping milk powder 9,000 miles across the planet is the price you pay to conquer the supermarket dairy aisle. “It would be great to get all of our food within a 10-mile radius of our house,” he says. “But once you’re in organic, you have to source globally.”

Hirshberg’s dilemma is that of the entire organic food business. Just as mainstream consumers are growing hungry for untainted food that also nourishes their social conscience, it is getting harder and harder to find organic ingredients. There simply aren’t enough organic cows in the U.S., never mind the organic grain to feed them, to go around. Nor are there sufficient organic strawberries, sugar, or apple pulp — some of the other ingredients that go into the world’s best-selling organic yogurt.

Powdered milk from New Zealand? Ew.

I wonder if corporations will find over the next couple of years that they simply can’t make the organic model work. That would be the good outcome. The bad would be that they use their massive clout to officially undermine organic standards. They’ve tried already, and surely won’t give up easily.

Anyway, here’s my favorite bit from the article:

The volatile supply [of organic ingredients] forced Heinz to put dried or fresh organic herbs in its organic Classico pasta sauce because it wasn’t able to find the more convenient quick-frozen variety.

Heaven forbid!